UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON

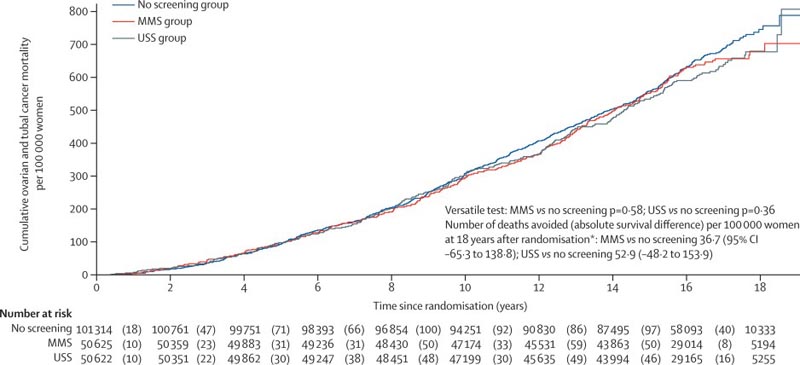

Background Ovarian cancer continues to have a poor prognosis with the majority of women diagnosed with advanced disease. We therefore carried out the UK Collaborative Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (UKCTOCS) to determine whether population screening can reduce deaths due to the disease. We report on ovarian cancer mortality after long-term follow-up in UKCTOCS. Methods In this randomized controlled trial, postmenopausal women aged 50 to 74 years were recruited from 13 centers in National Health Service trusts in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Exclusion criteria were bilateral oophorectomy, active ovarian or non-ovarian malignancies, or increased risk of familial ovarian cancer. The trial management system confirmed eligibility and randomized participants in blocks of 32 using computer-generated random numbers to annual multimodal screening (MMS), annual transvaginal ultrasound screening (USS), or no screening, in a 1:1:2 ratio. Monitoring was carried out through national registries. The primary outcome was death from ovarian or tubal cancer (WHO 2014 criteria) by June 30, 2020. Analyzes were performed by intent to screen, comparing MMS and USS separately without screening using the versatile test. Investigators and participants were aware of the type of screening, while the outcome review committee was blinded to the randomization group. This study is registered with ISRCTN, 22488978 and ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00058032. Results Between April 17, 2001 and September 29, 2005, of 1,243,282 women invited, 202,638 were recruited and randomly assigned, and 202,562 were included in the analysis: 50,625 (250%) in the MMS group, 50,623 ( 25.0%) in the USS Group and 101,314 (50.0%) in the group without screening. At a median follow-up of 16 3 years (IQR 15 1–17 3), 2,055 women were diagnosed with ovarian or tubal cancer: 522 (10%) of 50,625 in the MMS group, 517 (10%) of 50,623 in the USS group and 1,016 (10%) of 101,314 in the no-screening group. Compared with no screening, there was a 47.2% (95% CI 19.7 to 81.1) increase in stage I and a 24.5% decrease (-41.8 to -2 .0) in the incidence of stage IV disease in the MMS group. Overall, the incidence of stage I or II disease was 39 2% (95% CI: 16 1 to 66 9) higher in the MMS group than in the unscreened group, while the incidence of stage III or IV was 102% (- 21 3 to 2 4) lower. 1,206 women died from the disease: 296 (0 6%) of 50,625 in the MMS group, 291 (0 6%) of 50,623 in the USS group, and 619 (0 6%) of 101,314 in the unscreened group. No significant reduction in deaths from ovarian and tubal cancer was observed in the MMS (p = 0.58) or USS (p = 0.36) groups compared with the unscreened group.

Discussion Our results from the largest ovarian cancer screening trial to date show that at long-term follow-up (median 16 3 years after randomization), neither MMS nor USS, as used in UKCTOCS, significantly reduced deaths from ovarian and tubal cancer. There was a 47.2% higher incidence of stage I cancer and a 24.5% lower incidence of stage IV cancer, resulting in a 39.2% higher incidence of stage I or II cancer and a 102% lower incidence of stage I or II cancer. incidence of stage III or IV cancer in the MMS group than in the unscreened group. Screening the general population for ovarian and tubal cancer with any of the screening strategies cannot be recommended based on the evidence to date. Changes in stage distribution in the MMS group did not translate into reduced mortality, emphasizing the importance of having disease-specific mortality as a primary outcome in ovarian cancer screening trials. Interpretation The reduction in the incidence of stage III or IV disease in the MMS group was not sufficient to translate into lives saved, illustrating the importance of specifying cancer mortality as a primary outcome in screening trials. Because screening did not significantly reduce deaths from ovarian and tubal cancer, screening cannot be recommended in the general population. |

Research in context

Added value of this study

Long-term follow-up (mean follow-up > 16 years after enrollment) in the largest ovarian cancer screening trial, to our knowledge, provides definitive new evidence that none of the screening approaches used in the UKCTOCS reduced deaths from ovarian cancer, compared with no screening.

This result was despite a 47 2% increase in the incidence of women with ovarian and tubal cancer diagnosed at stage I and a 24 5% decrease in those diagnosed with stage IV disease in the multimodal group compared with the group without detection. However, it is important to note that there was only a 10 2% decrease in the overall incidence of stage III or IV disease.

Implications of all available evidence

Screening of the general population for ovarian and tubal cancer with any of the approaches used in UKCTOCS cannot currently be recommended.

We need a screening strategy that can detect ovarian and tubal cancer in asymptomatic women even earlier in its course and in a higher proportion of women than the tests used in the trial. Meanwhile, our results emphasize the importance of having ovarian and tubal cancer mortality as the primary outcome in screening trials.

Comments

A large-scale randomized trial of annual ovarian cancer screening, led by UCL researchers, failed to reduce deaths from the disease, despite one of the screening methods tested detecting cancers earlier.

Results from the UK Collaborative Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (UKCTOCS) have been published in a report in the medical journal The Lancet .

In the UK, 4,000 women die from ovarian cancer each year.

It is usually not diagnosed until it is in a late stage and is difficult to treat. UKCTOCS was designed to test the hypothesis that a reliable screening method that detects ovarian cancer earlier, when treatments are most likely to be effective, could save lives.

The latest analysis examined data from more than 200,000 women aged 50 to 74 at recruitment who were followed for an average of 16 years. Women were randomly assigned to one of three groups: no screening, annual screening using ultrasound, and annual multimodal screening that includes a blood test followed by ultrasound as a second-line test.

The researchers found that while the approach using multimodal testing was successful in detecting cancers at an early stage, neither screening method led to a reduction in deaths.

Earlier screening in UKCTOCS did not translate into saving lives. The researchers said this highlighted the importance of requiring evidence that any potential screening test for ovarian cancer actually reduced deaths, as well as early detection of the cancers.

Professor Usha Menon (MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL), principal investigator of UKTOCS, said: "UKCTOCS is the first trial to show that screening can definitely detect ovarian cancer earlier. However, this very large trial and Rigorous testing clearly shows that screening using the approaches we tested did not save lives, therefore we cannot recommend ovarian cancer screening for the general population with these methods.

"We are disappointed because this is not the result that we and everyone involved in the trial had hoped for and worked for for so many years. To save lives, we will need a better screening test that detects ovarian cancer earlier and in more women than multimodal detection strategy we use."

Women aged 50 to 74 were enrolled in the trial between 2001 and 2005. Screening lasted until 2011 and was either an annual blood test, monitoring changes in the CA125 protein level, or an annual vaginal ultrasound. Approximately 100,000 women were assigned to the non-screening group and more than 50,000 women to each of the screening groups.

The blood test detected 39% more cancers at an early stage (Stage I/II), while it detected 10% fewer late-stage cancers (Stage III/IV) compared to the no-screening group. There was no difference in the stage of cancers detected in the ultrasound group compared to the no-detection group.

The initial analysis of deaths in the trial was done in 2015, but there was not enough data at that time to conclude whether or not screening reduced deaths. By looking at five more years of follow-up data from the women involved, researchers can now conclude that the screening did not save lives.

Professor Mahesh Parmar, director of the MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL and lead author of the paper, said: "There have been significant improvements in the treatment of advanced disease over the last 10 years, since screening in our trial ended. Screening was not effective in women who do not have any symptoms of ovarian cancer; in women who do have symptoms, early diagnosis, combined with this improved treatment, can still make a difference in quality of life and potentially improve results. Getting a diagnosis quickly, whatever the stage of cancer, is extremely important for women and their families.

Professor Ian Jacobs, from the University of New South Wales (UNSW Sydney), a co-investigator who has led the ovarian cancer screening research program since 1985 and who was principal investigator of UKCTOCS from 2001 to 2014, said: " My thanks to the thousands of women, health professionals and researchers who made this trial possible. The multimodal screening strategy was successful in detecting ovarian cancer at an earlier stage, but unfortunately it did not save lives. That we would save lives. of thousands of women who are affected by ovarian cancer each year.