Note

This series of articles addresses the most common painful disorders of the foot and ankle: Morton’s neuroma, plantar fasciitis, and Achilles tendinopathy. The review summarizes current evidence on the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and non-surgical treatments of these conditions.

plantar fasciitis

Plantar fasciitis accounts for more than 1 million patient visits per year in the U.S. and typically presents with plantar heel pain. Fifteen years after diagnosis, approximately 44% of patients continue to experience pain. First-line nonsurgical treatment includes plantar fascia stretching and foot orthotics, followed by extracorporeal shock wave treatment, corticosteroid injection, or platelet-rich plasma injection.

Is plantar fasciitis a self-limiting condition? Plantar fasciitis can persist for many years, despite treatment. Up to 80% of patients will still feel pain at one year and 44% will still feel pain at 15 years. Should custom foot orthoses be prescribed for plantar fasciitis? Although foot orthoses have been shown to provide small improvements in the pain and function of plantar fasciitis, no difference has been shown between custom and prefabricated orthoses, the latter being much less expensive. |

plantar fasciitis

Definition and pathophysiology

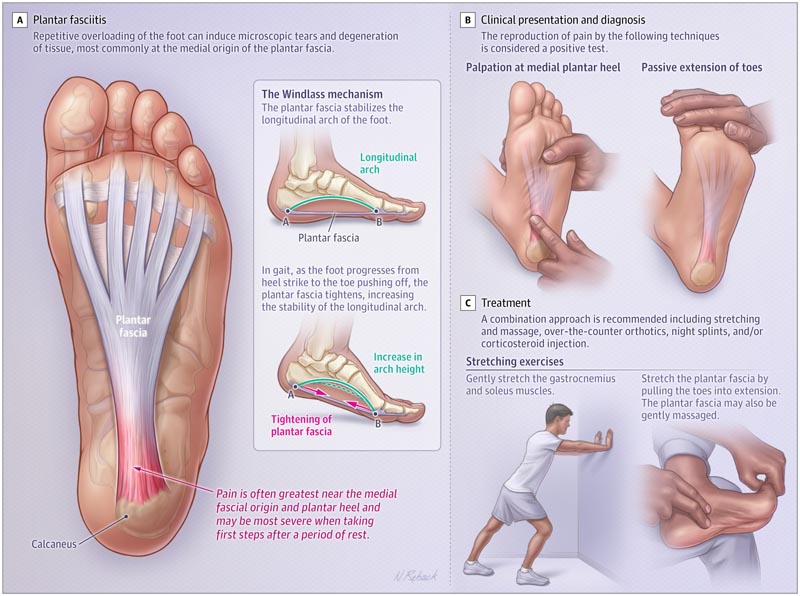

The plantar fascia is composed of three fascial bands (medial, central and lateral), which originate on the plantar aspect of the calcaneus and insert distally into the plantar plates of the metatarsophalangeal joints and the plantar bases of the proximal phalanges. The plantar fascia tightens when walking, stabilizing the longitudinal arch of the foot.

Although the pathogenesis of plantar fasciitis is not fully understood, repetitive mechanical overload can induce microscopic tears, primarily at the medial plantar origin of the plantar fascia. Tears may be associated with collagen degeneration, fiber disorientation, increased mucoid ground substance, and calcification.

The differential diagnosis of plantar heel pain includes tarsal tunnel syndrome, Baxter’s nerve entrapment, and calcaneal stress fracture. Radiographic plantar heel spurs may be more common in people with foot pain, but their significance in patients with heel pain is uncertain.

Epidemiology

Plantar fasciitis accounts for more than 1 million patient visits per year in the U.S., and approximately 62% of these visits occur in primary care offices. A study of 75,000 adults found that 1.10% (95% CI, 1.06%-1.34%) reported a diagnosis of plantar fasciitis in the past year, and women (1.19%) and men men (0.47%) had similar absolute rates. 17 Plantar fasciitis is most common in patients aged 45 to 64 years (8.2 outpatient visits per year per 1,000 people).

Risk factors for plantar fasciitis include decreased ankle dorsiflexion, high body mass index (BMI), and work that requires prolonged standing.

In a case-control study of 50 patients referred to physical therapy for previously untreated unilateral plantar fasciitis and 100 age- and sex-matched outpatient controls without previous plantar fasciitis or ankle injury, 18 compared to patients with more than 10 degrees of dorsiflexion of the ankle, there was a gradual increase in the odds of plantar fasciitis as ankle dorsiflexion became more limited.

Similarly, there is a progressive association between a BMI greater than 25 and plantar fasciitis; those with a BMI greater than 30 have the greatest association with plantar fasciitis compared with those with a BMI less than or equal to 25 (odds ratio, 5.6 [95% CI, 1.9-16.6]). People who reported spending most of their work time standing had a greater association with plantar fasciitis (odds ratio, 3.6 [95% CI, 2.5-39.2]).

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

The diagnosis of plantar fasciitis is based primarily on medical history and physical examination.

Patients often report pain in the sole of the heel, which is most intense with the first steps in the morning. The pain may worsen when standing for a long time. The physical examination most commonly identifies tenderness over the medial sole of the heel, which may be exacerbated by passive extension of the toes. A passive range of motion of the ankle should be performed to assess for decreased dorsiflexion, which is associated with plantar fasciitis, or any asymmetry compared to the unaffected side.

Imaging may be indicated when symptoms do not improve with conservative treatment or if another pathology may be the cause of the symptoms, such as calcaneal stress fracture. However, only 2% of heel images (4 of 215 heels) in patients with atraumatic plantar heel pain have radiological findings that affect initial treatments.

A meta-analysis of 21 observational medical imaging studies (1199 participants) demonstrated an association between plantar fascia thickness measured by ultrasound in plantar fasciitis compared with controls (mean difference [MD], 2.00 mm [CI]. 95%, 1.62-2.39]; p < 0.001).

MRI shows T2-weighted hyperintensity at the origin of the plantar fascia at the calcaneal tuberosity as well as thickening of the plantar fascia, but should only be used when the clinical diagnosis is unclear.

Treatment

Plantar fasciitis is usually self-limiting , but can persist for months or years. A study of 174 patients reported that 80.5% (95% CI, 73.5%-85.6%) of patients had symptoms at 1-year follow-up and 44.0% (95% CI, 35 .9%-51.8%). For patients whose symptoms resolved, the mean (range) duration of symptoms was 725 (41-4018) days.

Patients should avoid activities that exacerbate symptoms.

Treatments consist of a combination of stretching, bracing, physical therapy, night splints, or injections (corticosteroids or platelet-rich plasma [PRP]).

A small randomized trial of 29 participants found that oral celecoxib, 200 mg once daily, did not significantly improve pain or disability at any time point up to 6 months after baseline versus placebo.

Among 30 patients randomly assigned to undergo home stretching and 27 randomly assigned to undergo physical therapist-guided physical therapy, home stretching improved mean VAS pain scores at 6 weeks (23-point decrease; P < 0.001 ) and 1 year (28 point decrease) decrease; P < 0.001). VAS scores were not significantly different between the home stretching and physical therapy groups at any time point. 24 The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for plantar heel pain is -8 mm (95% CI -12 to -4) on a VAS.

Foot orthoses replace the insole of the patient’s shoe to decrease stress on the plantar fascia and reduce ground reaction forces beneath the calcaneal tuberosity. A 2018 meta-analysis of 19 randomized clinical trials (1660 patients) of orthoses reported that foot orthoses were associated with less pain at 7 to 12 weeks compared with sham orthoses (standardized MD [SMD], −0.27 [ 95% CI, −0.48 to −0.06]).

Custom orthoses , designed to fit each individual patient, are not superior to prefabricated ones, although they are more expensive. In a randomized clinical trial of 135 participants, prefabricated orthoses improved VAS pain scores (scale range, 0 to 100) at 3 months compared with sham orthoses (MD, 8.7 points [CI 95 % −0.1 to 17.6]; P = 0.05 ). Prefabricated orthoses improved VAS pain scores similarly to custom-made orthoses at 3 months (MD, 1.3 [95% CI, −7.6 to 10.2]) and 12 months . 27

Night splints dorisflex the ankle and extend the toes during sleep. In a small randomized crossover trial of 37 patients with recalcitrant plantar fasciitis (symptoms >6 months; mean duration, 33.4 months), those initially assigned to undergo splinting had more improvement over the course of the study compared with those assigned to not receive active treatment (improvement of 15.4 from baseline on the Mayo Clinical Scoring System; P < 0.001; MCID not given), whereas those assigned to receive no treatment had no change in symptoms. At 6 months follow-up, 73% of all patients were satisfied, but only 36.4% did not feel pain.

Corticosteroid injections (CSI) can provide short-term pain relief for plantar fasciitis.

A Cochrane review found that CSIs were associated with VAS heel pain improvement in the short term (<1 month) compared with placebo (MD, −6.38 [95% CI, −11.13 to − 1.64]; 5 studies; 350 participants), but the association disappeared after 1 to 6 months (MD, −3.47 [95% CI, −8.43 to 1.48]; 6 studies; 382 participants ).

In a meta-analysis of 47 randomized clinical trials (2989 patients), corticosteroid injections (CSI) were associated with greater pain reduction over 0 to 6 weeks than foot orthoses (SMD, −0.91 [95% CI). , −1.69 to −0.13]) or autologous blood injection (SMD, −0.56 [95% CI, −0.86 to −0.026]). However, this difference in favor of corticosteroid injections (CSI) did not persist beyond 6 weeks. CSIs were associated with inferior pain outcomes compared with dry needling (SMD, 1.45 [95% CI, 0.70-2.19]) and PRP injection (SMD, 0.61 [95% CI 95%: 0.16-1.06]) between weeks 13 and 52.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections for plantar fasciitis may be more effective than corticosteroid injections (CSI) in the long term.

In a clinical trial of 90 patients, CSIs, PRP injections, and placebo injections improved pain and function at 18 months. 31 However, ICS improved pain and function more than PRP and placebo at less than 1 month of follow-up, while PRP improved pain more than ICS and placebo at 6 to 18 months.

A meta-analysis of 15 trials (811 patients) reported that, compared with CSI, PRP was not associated with better function at 1 month based on the American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score (SMD, 0.982 [CI 95% CI, −1.302 to 3.265]; P = 0.4), but a significant improvement in favor of PRP was shown at 12 months (SMD, −2.728 [95% CI, −4.782 to −0.674]; P = 0.009). 32 VAS scores also improved with PRP at 3 and 12 months (SMD at 12 months, −1.71 [95% CI, −3.13 to −0.283]; P = 0.019).

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy ( ESWT), performed by orthopedists, physiatrists or podiatrists, involves the application of high-pressure pulsating sound waves to the plantar fascia. A meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials (935 participants) reported that ESWT was associated with greater pain reduction than placebo (SMD, 1.01 [95% CI, −0.01 to 2.03]; P = 0 .05). In a randomized clinical trial of 100 patients, ESWT treatment produced less pain in the VAS score compared with CSI at 6 months follow-up (mean [SD] pain score of 2.1 [0.7] for ESWT vs. 2.9 [1.3] for CSI; score range, 0-10; 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating the worst pain imaginable; P < 0.001).

Surgical intervention may be considered if nonsurgical treatment is ineffective. Limited data support one surgical option over another, and reported success rates of surgical procedures vary.

Partial plantar fasciectomy , or partial plantar release, produces a wide range of patient satisfaction (48.8% and 89.5% satisfied). Gastrocnemius release has been used for chronic plantar fasciitis; In a randomized clinical trial comparing gastrocnemius release with open plantar fascia release, no significant differences in patient satisfaction were found between the procedures (85.8% satisfaction with gastrocnemius release vs. .5% with plantar fascia release; P = 0.27).

Complications

Injection site pain is the most common complication of corticosteroid injections (CSI) I for plantar fasciitis, and rupture of the plantar fascia occurs in approximately 2.4% of patients who undergo it. inject corticosteroids, most commonly after multiple CSIs (mean 2.63 injections).

Reported complications of extracorporeal shock wave therapy included temporary pain at the treatment site, mild skin irritation, and bruising.

Complications of plantar fascia release include wound complications and midfoot dorsal pain, which may be due to altered foot mechanics. Gastrocnemius release can cause sural nerve injury and weakness in plantar flexion.