Fibromyalgia syndrome ( FMS) is a common condition characterized by persistent, widespread pain associated with fatigue, sleep disturbances, impaired cognitive and physical function, and psychological distress. In the International Classification of Diseases (CDC) FMS is classified as chronic primary pain (ICD11).

FMS (MG30.01) has had many names such as fibrositis or fibromyositis. However, it is now accepted that these terms are inappropriate, incorrectly implying muscle inflammation as the primary cause of pain. Although its etiology is still unknown, advances in research have shown that it is likely due to alterations in pain processing within the nervous system.

Diagnosing fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) can be challenging as there are no laboratory investigations to confirm its presence. Symptoms are fluctuating and may not easily correspond to established medical diagnostic categories. Therefore, there is a fundamental need to support physicians interested in the management of this condition.

| Scope and purpose |

The guide has been adapted to provide information to doctors and patients, around a diagnostic meeting of clinical doctors and specialist surgeons. The purpose is to provide help to guide clinicians in improved and timely diagnosis and early management.

| FMS diagnostic consultation |

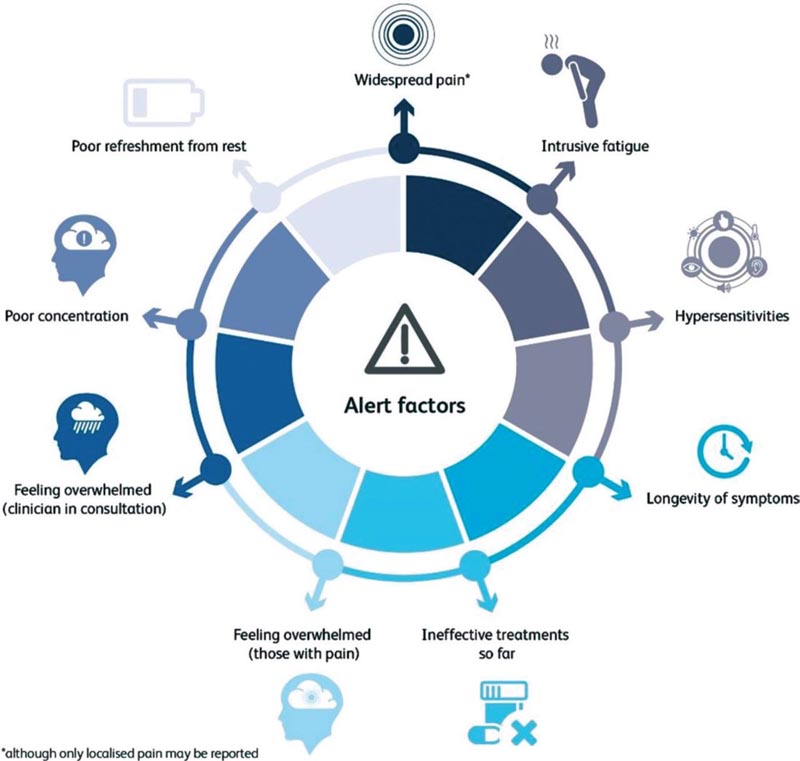

When reviewing a patient, the finding of certain characteristics may lead to the need to formally evaluate FMS.

> Generalized pain: pain in multiple regions of the body .

Patients with FMS may not report generalized pain but only focal pain. Therefore, it is important to ask about the presence of pain elsewhere.

> Intense fatigue . It can be physical, cognitive or emotional (motivational fatigue).

> Hypersensitivity. Increased sensitivity to sound, light or ambient temperature, which may represent alterations in the sensory processing of the central nervous system. Tenderness on clinical examination may indicate abnormal mechanical tenderness.

> Persistent symptoms . Pain that has been present or recurring for >3 months is considered “chronic” or “persistent.”

> Ineffective treatments so far . Pharmacological treatments are often ineffective while rehabilitation focused solely on mobilization or classical musculoskeletal physiotherapy may also be ineffective and may even increase pain, suggesting that abnormal pain processing predominates.

> Patients feel sad . Many symptoms and their consequences, such as disability and distress, can be difficult to understand and patients often feel distressed.

> Doctors feel sad . Health professionals may feel overwhelmed by the profusion of symptoms.

| Diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome |

The diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) has become the domain of the specialist but can be initiated by doctors or professionals who feel prepared to do so. Making the diagnosis of fibromyalgia is likely to represent a significant moment in the patient’s life and therefore it is suggested that the clinician set an appropriate scene.

The best guideline based on the most recent evidence is that of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) from 2016, whose diagnostic criteria are as follows:

> Widespread Pain Index (WPI) ≥7 and Symptom Severity Scale (SSS) score ≥5 OR WPI 4–6 and SSS score ≥9.

> Generalized pain, defined as pain in at least 4 of the 5 regions of the body.

> Symptoms have been present at a similar level for at least 3 months. Patients with symptoms below this threshold may be diagnosed with FMS if symptoms above the threshold were recently documented. If in doubt, refer to a specialist with experience in diagnosing fibromyalgia (usually a pain specialist or rheumatologist).

| Setting the scene when making the diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome |

Recommendation (evidence) > Recognize the patient’s life situation (E2) > Allow sufficient time (E1 + E2) > Arrange additional appointments or refer when necessary, explaining the decision (E2) > Allow a face-to-face diagnostic consultation if possible (E2) |

| Key for evaluating the evidence: E1 = opinion of the user or caregiver; E2 = professional or the opinion of interested parties. |

| Differential diagnoses |

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is not a diagnosis of exclusion and often exists alongside other conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or ankylosing spondylitis).

There are no specific diagnostic tests for FMS, but it is recommended that treatable conditions be investigated.

| When is the diagnosis uncertain ? |

> Reasons for diagnostic uncertainty may include:

• Fluctuating symptoms just below the diagnostic threshold for ACR.

• Many health conditions (e.g., inflammatory diseases or depression) independently impact ACR WPI or SSS.

> Symptoms evolve and it is advisable to share any diagnostic dilemma with the patient, applying a “watchful waiting” strategy.

> A “safety net” is often necessary, sharing important symptoms or signs with the patient that may indicate alternative diagnoses.

> Sensitization does not have temporal linearity, that is, there is no evidence that subthreshold symptoms will always progress to a diagnosis of FMS.

> Diagnostic uncertainty should not prevent accepting a shared diagnostic plan using the best evidence for the management of diseases with chronic pain.

| Clinical management |

Clinical management is beyond the scope of this diagnostic guide and is discussed elsewhere, but some general principles are suggested.

| Clinical management and essential information |

Recommendation (evidence) > Pain management, including information, rehabilitation methods and connection with non-clinical support groups, which can reduce suffering. This should be done in parallel to the investigation (E1+E2) > Established pain medications or normal musculoskeletal physiotherapy, which are often ineffective or even physiotherapy can cause harm, so the patient should be warned (E1+E2) > FMS is a chronic condition that sometimes requires planning and reviews in primary or secondary care. The development of a therapeutic relationship is crucial if the experience of the doctor and the patient is used effectively for the management plan (E1+E2) |

| Perioperative care specific to surgical practice |

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a common condition, and while FMS pain itself is not amenable to surgery, many patients with fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) will undergo surgery for a variety of reasons.

Nociceptive pain ( pain due to mechanical movements or inflammatory stimuli) may be amenable to surgery.

Neuropathic pain ( pain caused by injury to the nervous system) can sometimes be amenable to surgery.

However, most chronic pain is neither nociceptive nor neuropathic.

Its mechanism is called nociplastic , so the main cause of pain is its abnormal processing. When performing surgery, there are some important factor alerts that suggest that the pain may be nociplastic.

| SFM alarm factors in practice |

Recommendation (evidence) a) Pain > Pain disproportionate to the pathology, current or past, at the site of current pain or other regions of the body (E2) > Chronic pain in more than one site (CD) b) Efficacy of pain treatment > Pain that did not improve with previous surgeries for this or another problem. Includes recurrence of pain, immediately or months after surgery (E2) > History of repeated surgeries for this or another painful problem (E2) > Treatment with medications or physiotherapy is not effective or there is even worsening of pain (E2, DC) c) Other factors > Fatigue, non-restorative sleep, psychological distress and cognitive impairment (such as short-term memory or thinking problems) (E2) > Intense perioperative pain and high requirement for analgesia in previous operations (E2) |

If nociplastic pain or FMS is suspected, the choice of specialist to whom the patient will be referred after surgical evaluation will depend on the local situation, and may include returning to the general practitioner or a pain clinic. Communication with the patient is vital and may require delicacy, both in surgery and in the medical clinic.

| Decision to operate |

Patients with fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) often respond differently to surgical interventions than patients without FMS but with a similar injury, and their management may benefit from the participation of a multidisciplinary team. It should be noted that often the failure of surgery to relieve pain may only manifest itself several months later, due to the significant placebo effect that surgery usually causes, while certain anesthetics may temporarily decrease nociplastic pain by reducing central sensitization.

The true long-term effect of surgery on pain is impossible to measure outside of clinical trials. Increased pain after surgery may also reflect an independent FMS pain flare in patients without a formal FMS diagnosis. Surgeons should be aware that patients who have some features of FMS (even if these do not support a formal diagnosis of FMS) may achieve less pain relief with surgery.

Mainly patients with regional pain (e.g. painful knee osteoarthritis) may have symptoms similar to those of fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) such as fatigue, hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli, poor sleep, poor memory or psychological distress , without meeting the SFM criteria. The causes of these symptoms are unknown and are not considered psychological, although psychological distress is often present.

It is believed that the degree of symptomatology is related to the degree of sensitization of the nervous system.

Research indicates that even below the threshold for diagnosis, surgical outcomes may be affected, as patients with high scores are likely to be at risk for little pain improvement after surgery.

In contrast, the response to surgery in patients with high sensitization scores is diverse, and many patients have good outcomes. Six months after knee or hip replacement surgery, two-thirds of patients with high preoperative sensitization scores, but not fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS), reported improvement in regional pain. but also generalized symptoms, such as fatigue and insomnia. However, the remaining third experienced no improvement or, worse still, there was an increase in pain after their operation. Unfortunately, there is still no reliable tool to predict who will respond to surgery.

| Limitations |

The guideline was compiled using standards established by AGREE ( New International Tool for Assessing the Quality and Reporting of Practice Guidelines 2010). The recommendations were based on the consensus of the panel, considering the existing literature. More randomized and controlled studies are still lacking.

However, due to a paucity of evidence-based randomized controlled trials specifically informing the diagnosis and management of FMS, many of the recommendations were based on the expert opinion of service users and professionals; according to the national service framework for long-term conditions.

| Implications for implementation |

In consultations, the doctor should take into account the warning characteristics of FMS and use the ACR 2016 criteria for diagnosis. FMS can coexist with other medical conditions and the diagnosis can be made with a detailed history and examination along with standard blood tests to exclude other treatable conditions.

For the surgeon, when considering a patient’s suitability for surgery, he or she must be aware of the warning characteristics of FMS and nociplastic pain. If a patient with FMS presents and has a surgical indication to treat the pain, one must consider whether her pain is treatable with surgery and communicate this effectively. If surgery is indicated, the participation of the multidisciplinary team may be useful to achieve optimal results.