Summary

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo ( BPPV), caused by stubborn crystals ("stones") in the semicircular canals of the inner ear, is the most common cause of brief symptoms of vertigo secondary to head and body movements. Diagnosing and treating it is easy to do in the doctor’s office.

This article reviews the differential diagnosis for patients presenting with dizziness and vertigo, the pathophysiology of BPPV, how to diagnose it using maneuvers to provoke symptoms and nystagmus, how to interpret the pattern of nystagmus to determine where the stones are, and how to treat it using different maneuvers to reposition ( "roll") the rocks back to where they belong.

Key points

|

Dizziness is a common complaint that can affect people of all ages, with approximately 15% of American adults reporting balance problems or dizziness . It is the reason for many emergency room visits, secondary to benign conditions (e.g., vestibular conditions, migraine, psychogenic conditions) and serious conditions (e.g., stroke, inflammatory disease of the central nervous system, tumor intracranial or hemorrhage).

Unfortunately, balance disorders are often difficult to diagnose and manage, due in part to the subjective symptoms and the complexity of the neurological, cardiovascular, metabolic, toxic, vestibular, and psychiatric conditions that can cause them. Symptoms may also be similar to those of life-threatening conditions, making diagnosis difficult.

This article provides an update on benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), a common balance disorder, and how to distinguish it from other causes of dizziness, vertigo, and imbalance with easy position-changing maneuvers. We also discussed the best way to treat it with repositioning maneuvers.

Dizziness vs vertigo

Patients use the term dizziness to describe several different sensations, but medically speaking it is different from vertigo . Dizziness is any distortion of the sensation of where one is within a space, while vertigo is a false sensation of movement , specifically rotation or spinning.

A complete medical history can differentiate between these sensations and pinpoint a cause.

Questions should focus on the following:

- Quality of symptoms, such as vertigo, oscillopsia (the illusion that objects are moving from side to side), general imbalance, or lightheadedness.

- Time course of symptoms, such as speed of onset, duration, circumstances of onset, time since the initial episode, and frequency of episodes.

- Associated factors, such as migraine or changes in vision, hearing, or breathing

- Exacerbating and relieving factors, such as head or body movements, closing or opening the eyes, looking in one direction or another, entering or leaving an occupied field of vision, coughing, sneezing, or loud sounds.

- Other relevant medical history, such as vision problems, lower extremity disabilities, medications that can cause dizziness, diabetes, neuropathy, cerebrovascular disease, stroke, neck pain, seizures, hypertension, heart problems, or ototoxicity.

Common vestibular disorders have typical characteristics that are key to quickly narrowing down the cause of symptoms and making appropriate referrals.

A common cause of dizziness and vertigo

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo ( BPPV) is one of the most common vestibular causes of dizziness. Royl et al reported that it was the most common diagnosis in patients presenting to the emergency department with dizziness . Its prevalence increases with age and most frequently affects people over 40 years of age. It is more common in women than in men.

Although BPPV is common, it often goes unrecognized leading to costly and unnecessary diagnostic procedures, referrals and treatments. If left undetected and untreated, BPPV can also lead to poor quality of life and falls, the leading cause of trauma-related injuries and hospitalizations in older adults.

Brief episodes of vertigo associated with movement

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo ( BPPV) presents as brief episodes of vertigo, usually lasting seconds to minutes, and associated with head movement, neck movement, or general position changes. Common triggers include:

- Turning over in bed.

- Look up or down.

- Getting up from a supine position.

- Lie down from a sitting position.

- Leaning forward.

There may be a short latency of seconds between the initial position change and the corresponding symptoms. Patients may also experience nausea or emesis during an episode and report a general feeling of floating or imbalance.

Causes of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)

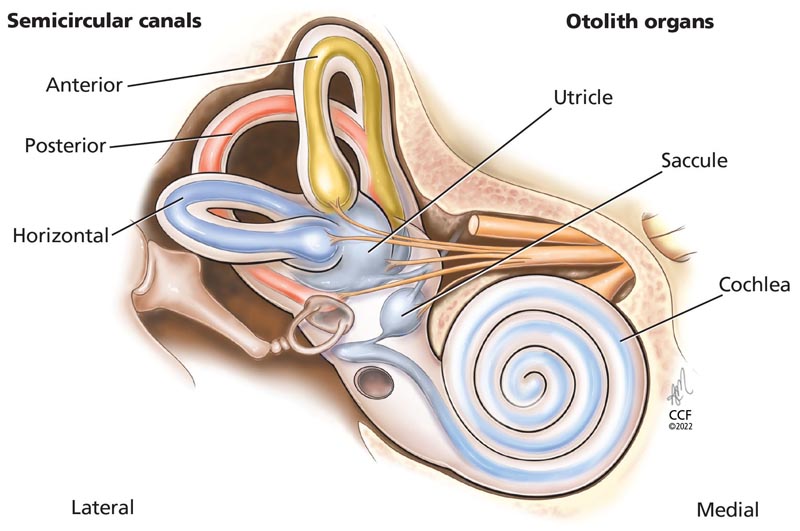

Deep in the petrosal part of the temporal bone is the membranous labyrinth, housed within the bony labyrinth (Figure 1). The membranous labyrinth is filled with fluid (endolymph) and houses the cochlea and vestibular structures: the 3 semicircular canals - anterior, posterior and horizontal (also called lateral) and the 2 otolith organs (saccule and utricle). The semicircular canals detect angular acceleration and the otolith organs detect linear acceleration, providing our internal signals for position orientation in space, movement, gaze stabilization, and postural control.

Figure 1

The semicircular canals (anterior, posterior, horizontal) detect angular acceleration and the otolith organs (saccule, uticle) detect linear acceleration, providing internal signals for orientation of position in space, movement, gaze stabilization and postural control .

Body movements cause the fluid in the semicircular canals to move and stimulate the cilia of the sensory hair cells. This triggers the transmission of neural signals to the brain to initiate appropriate reflex responses for eye, head, and postural adjustments. These reflex movements allow us to see things clearly when our head and body are moving and prevent us from falling.

The 3 semicircular canals are placed at 90 degree angles to each other and can therefore detect rotation in all directions. Thus, for example, when turning the head to look over the right shoulder, the right horizontal semicircular canal is excited and the left horizontal is inhibited.

The utricle and saccule are sensitive to gravity and contain dense crystals called otoconia that rest on the sensory organs. With linear movements (e.g., leaning to one side), the otoconia move and signal reflex responses similar to those of the semicircular canals to maintain balance of the eyes, head, and body.

BPPV is caused by floating otoconia that have become detached from the otolith organs as a result of injury, infection, diabetes, migraine, osteoporosis, prolonged bed rest, or aging. Detached otoconia may accumulate in the semicircular canals. Since each semicircular canal is oriented in a different plane in space, when detached otoconia accumulate in one or more of them, they can be stimulated by changing position and cause vertigo and nystagmus .

Most cases of BPPV are idiopathic or caused by head trauma, but may result from other vestibular disorders (eg, Menière’s disease, labyrinthitis) or central nervous system disorders (eg. , migraine, multiple sclerosis).

Recent evidence suggests that BPPV has a seasonal aspect , perhaps related to varying levels of vitamin D throughout the year. Otoconia are composed of calcium carbonate and therefore could have risk factors for demineralization, similar to bones . Maia et al 12 analyzed 214 patients diagnosed with idiopathic BPPV in Brazil over 5 years and found that significantly more patients presented in autumn and winter than in spring and summer. This suggests that lower vitamin D levels, due to less sunlight, could be contributing to the seasonality of BPPV.

Diagnostic maneuvers

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo ( BPPV) is relatively simple to diagnose and treat. By moving the patient into different positions, observing his eye movements, and asking him if he feels his head spinning, doctors can determine which semicircular canal is being stimulated. Otoconia in the posterior semicircular canal accounts for up to 90% of cases, and otoconia in the horizontal canal accounts for most of the remainder, while involvement of the anterior semicircular canal is relatively rare and is usually due to failed repositioning maneuvers. to eliminate otoconia from the posterior canal.

Nystagmus consists of the oscillation of the eyes and can be horizontal (to the side and back), torsional (rotational in nature) or vertical (up or down and back), or a combination of some or all three. The direction and characteristics of eye movements correspond to the semicircular canal stimulated during positioning. Symptoms are brief, often lasting less than 60 seconds.

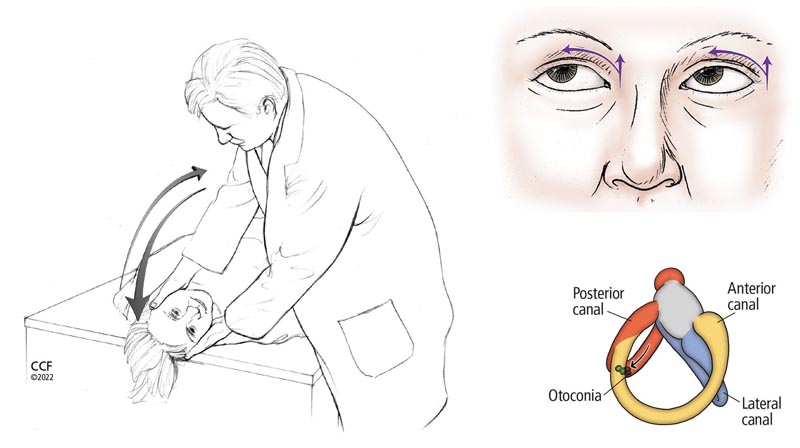

Dix–Hallpike maneuver

Variants of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) that affect the vertical semicircular canals (i.e., anterior and posterior) are diagnosed using the Dix-Hallpike maneuver. It consists of 2 position changes (sitting to supine and supine to sitting) with the patient’s head rotated 45° (Figure 2). When the patient is moved from the sitting position to the supine position, the clinician may observe the excitatory eye movement pattern of the canal with the otoconia, with horizontal nystagmus toward the affected ear and any of the following:

- Above (if the otoconia are in the posterior canal).

- Downwards (if they are on the previous channel).

Figure 2

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver to detect otoconia in the posterior or anterior semicircular canals. If otoconia is suspected to be in the right ear, the patient sits upright with the head turned 45° to the right; If otoconia is suspected to be in the left ear, the patient turns his head to the left. The doctor then quickly moves the patient to a supine position with the head hanging and checks for signs of nystagmus, and the patient reports any symptoms (eg, dizziness, vertigo). After 60 seconds, the patient is returned to a sitting position with the head still turned and the doctor again observes the symptoms and signs. During the maneuver, movement of the otoconia within the right posterior semicircular canal (in the lower right image) elicits an excitatory response (i.e., nystagmus) to the right and upward, as indicated by the arrows in the upper right image.

When the patient moves from supine to sitting, a pattern of reverse nystagmus should be observed, indicating inhibition of the channel with otoconia, with torsional nystagmus toward the healthy side and any of the following:

- Down (for the rear channel).

- Up (for the previous channel).

The maneuver is then repeated with the patient’s head turned to the other side, that is, to evaluate both the right and left sides.

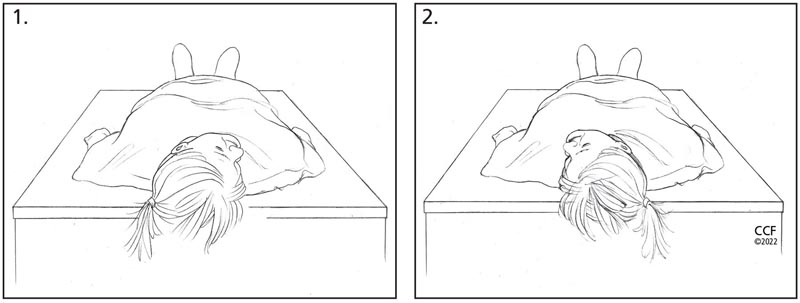

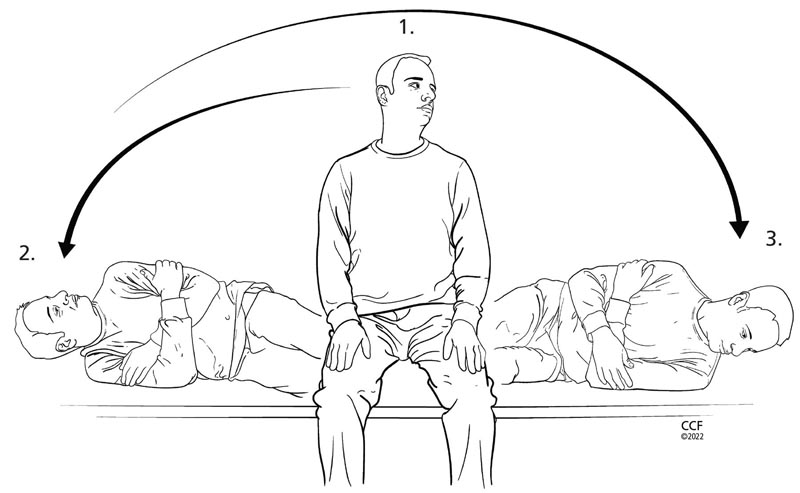

Supine roll test

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver does not always cause vertigo and nystagmus in cases of BPPV that are due to otoconia in the horizontal semicircular canal. Therefore, the supine twist test is recommended as a second screening maneuver (Figure 3).

Figure 3

The supine turn test to detect otoconia in the horizontal semicircular canals. (A) With the patient in the supine position, the clinician quickly turns the patient’s head to the right and assesses the patient’s horizontal nystagmus and symptoms. (B) After 30 to 60 seconds, the doctor quickly turns the patient’s head to the left and again observes whether there is horizontal nystagmus and symptoms. The direction of nystagmus (i.e., geotropic vs. apogeotropic) with changes in head movement indicates the affected horizontal channel.

A positive sign of BPPV during this test is horizontal nystagmus in both right and left head positions. If the nystagmus is in the same direction that the head is turned, the pattern is called geotropic . If it is in the opposite direction, the pattern is called apogeotropic .

Consult if in doubt

Recent clinical practice guidelines indicate that the appropriate diagnosis of BPPV is made when both patient-reported symptoms and the appropriate nystagmus pattern during position changes are observed. However, false negative results can occur . When BPPV is strongly suspected based on history, but Dix-Hallpike and supine roll maneuvers are negative, the patient should be referred to a vestibular therapist or vestibular audiologist for further evaluation.

Treatment maneuvers

Once benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) has been diagnosed, treatment is based on the affected semicircular canal. This involves a series of head and body movements guided by the doctor to move the otoconia out of the semicircular canal and back into the utricle, with the help of gravity. The process is simple and can be performed on a standard exam chair that can be fully reclined or on a table. These maneuvers can often provide immediate and long-lasting relief. In various studies, its effectiveness ranged from approximately 76% to 93%.

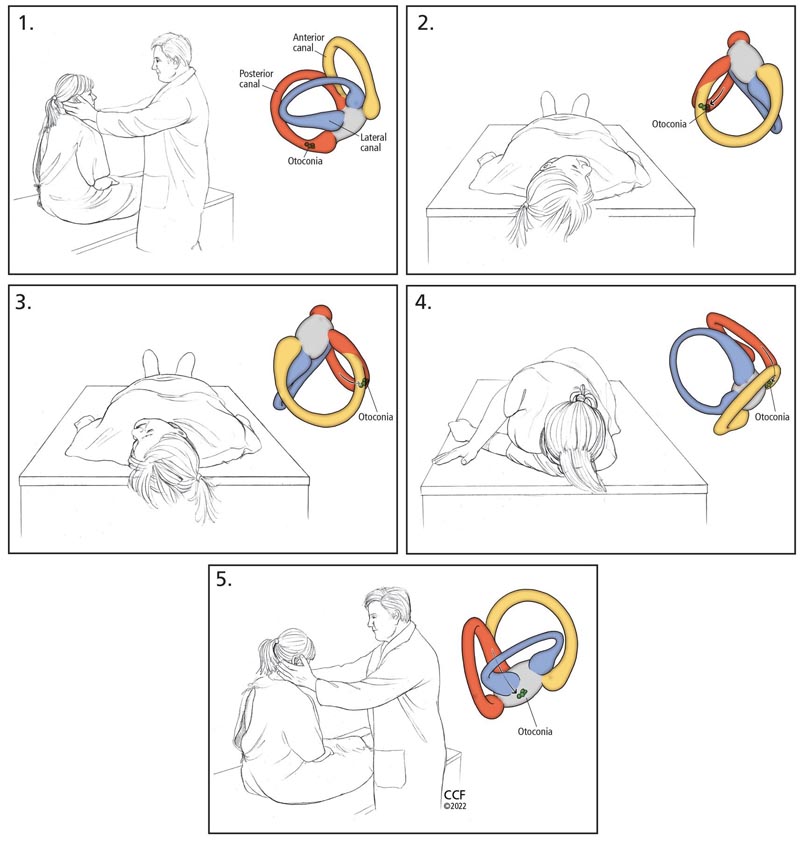

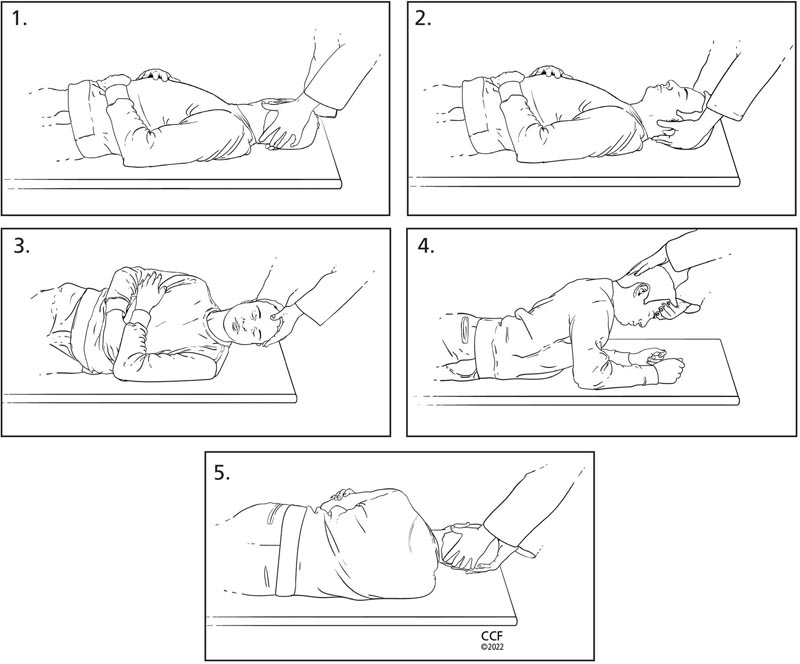

Epley maneuver for posterior or anterior canal BPPV

In 1992, Epley described a series of head and body movements to dislodge the otoconia from the vertical (i.e., posterior and anterior) semicircular canals. The procedure is easy to perform but requires careful attention to keep the patient’s head and body in the proper position throughout the maneuver (Figure 4). Additionally, the patient’s eyes should be monitored throughout each stage of the maneuver to observe the pattern of nystagmus , which should remain consistent with that observed during the Dix-Hallpike or supine twist maneuver. Consistent nystagmus patterns ensure that the clinician has not moved the otoconia to a different semicircular canal instead of the otolith organs.

Figure 4

The Epley maneuver to remove otoconia from the posterior or anterior semicircular canals:

- Place the patient in a sitting position on the bed and turn the head 45° toward the ear with the suspected otoconia. Color inserts show the movement of the otoconia.

- Quickly move the patient to a supine position with the head rotated and extended downward.

- Move the patient’s head to the other side, taking care to keep it in the correct plane. The final position after the turn should be 45° towards the unaffected ear, extended downward.

- Assist the patient onto the unaffected side with the patient’s chin at 45° toward the unaffected ear (the patient will look toward the floor in this position).

- Finally, help the patient return to a sitting position, keeping the head turned over the shoulder.

Semont maneuver, an alternative to the Epley maneuver

The Semont maneuver is a suitable alternative to the Epley maneuver for treating vertical canal BPPV. This maneuver requires rapidly moving the patient through a series of head and body positions (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Semont maneuver, an alternative way to remove otoconia from the posterior or anterior canals:

Semont maneuver, an alternative way to remove otoconia from the posterior or anterior canals:

- Place the patient in a sitting position on the bed and rotate the head 45° away from the ear with the suspected otoconia in the vertical semicircular canal.

- Quickly move the patient onto his side with his nose toward the ceiling.

- Quickly move the patient up and to the other side with the head at the same 45° angle with the nose facing the floor. The examiner then helps the patient sit up, keeping the head at 45° from the ear with suspected benign paroxysmal vertical semicircular canal positional vertigo (BPPV).

Note : The head position described in step 1 is used for BPPV of the posterior semicircular canal. The patient should turn the head 45° toward the ear with suspected vertical semicircular canal BPPV if the anterior semicircular canal is involved.

As with the Epley maneuver, the clinician should focus on nystagmus patterns throughout the maneuver, which should be consistent with those observed during the diagnostic examination (eg, the Dix-Hallpike maneuver).

The turning maneuver for the treatment of BPPV of the horizontal canal

As noted above, proper diagnosis of BPPV of the horizontal semicircular canal on the affected side requires careful review of the nystagmus pattern ( geotropic vs. apogeotropic ) during the supine twist test.

Geotropic horizontal channel BPPV is more common than apogeotropic . Often, listening to the patient describe their symptoms and observing nystagmus patterns helps determine which side is affected and should be treated. Referral to a vestibular specialist is warranted to ensure correct side and appropriate treatment. Additionally, many other disorders can present with horizontal change-of-direction nystagmus, and in these cases a thorough evaluation should be performed to confirm or rule out BPPV.

Since geotropic horizontal semicircular canal BPPV is more common than the apogeotropic variant , clinicians may perform the 360° roll maneuver. If the apogeotropic variant is present, the Gufoni maneuver can be performed. Following the steps shown in Figure 6 ensures proper positioning of the head and body to remove debris from the affected horizontal channel. It is imperative to support the patient’s head during all movements. The patient should remain in each position until symptoms and nystagmus disappear.

Figure 6

Turning maneuver (360°) to clear otoconia from the horizontal semicircular canal:

- Place the patient supine and turn the head 90° toward the ear with the suspected otoconia in the horizontal semicircular canal.

- Next, rotate the patient’s head toward the center, with the head elevated 30°.

- Maneuver the patient sideways (90°) toward the unaffected ear.

- Move the patient to the prone position with elbows flexed. Note: Sometimes treatment may end in this position (called the 270° maneuver).

- Finally, help the patient turn away from the affected ear, completing a full 360° rotation.

Care route for patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) The following care pathway is a suggested guide for evaluating and treating BPPV.

|