Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding ( AGIB) is a common emergency in the United States of America, with two recent large national studies estimating an annual incidence between 67 and 78 cases per 100,000 people. The condition represents a large burden on the healthcare system because its incidence is higher than most other gastrointestinal (GI) disorders. Furthermore, once identified, it is estimated that more than three-quarters of patients with UGIB require hospitalization, and their in-hospital mortality is among the highest of gastrointestinal diseases.

Within the diagnosis of UGIB, there are two different entities that complicate the epidemiology due to various risk factors, causes and interventions. Bleeding from gastric or esophageal varices is most commonly attributed to portal hypertension due to end-stage liver disease, while non-variceal bleeds represent the remaining presentations from other causes.

The incidence of non-varicose UGIB is significantly higher than that of varicose veins; however, its mortality is lower.

Furthermore, while the incidence and mortality of non-variceal UGIB have decreased dramatically in recent decades, this is not true for variceal hemorrhages.

Safely discharging patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AGIB) represents an ongoing challenge for clinicians. Although bleeding can be treated acutely with endoscopy and other interventions, patients are often re-exposed to potential precipitating factors shortly thereafter (e.g., anticoagulation and ethanol) or the driving stimulus is not immediately eradicated ( e.g., portal hypertension and Helicobacter pylori). As such, it is important for physicians to have access to informed metrics, such as readmissions, rebleeding, and mortality rates after discharge, so they can effectively counsel patients about their risk.

In other areas of medicine, similar metrics for pneumonia, heart failure, and myocardial infarctions represent quality indicators. There is also a financial argument that decreasing preventable readmissions will help the burden on the overall healthcare system.

Despite the advantage of having up-to-date metrics, there is currently little available aggregating data from numerous studies focusing on subsets of the UGIB population. This systematic review and meta-analysis summarizes the literature on readmission rates for adults discharged after UGIB, with stratification of clinically important subgroups.

Background and objective

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a common emergency, with high rates of hospitalization and in-hospital mortality compared to other gastrointestinal diseases. Although readmission rates are a common quality metric, little data is available for UGIBs. This study aimed to determine the readmission rates of patients discharged after UGIB.

Methods

In accordance with PRISMA guidelines, MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, and Web of Science were searched through October 16, 2021. Randomized and non-randomized studies reporting hospital readmission of patients after UGIB were included. Abstract screening, data extraction, and quality assessment were performed in duplicate. A random effects meta-analysis was performed, with measured statistical heterogeneity. The GRADE framework, with a modified Downs and Black tool, was used to determine the certainty of the evidence.

Results

Seventy studies were included from 1847 selected abstracts, with moderate inter-rater reliability. Within these studies, 4,292,714 patients were analyzed with an average age of 66.6 years, 54.7% being male.

HDA had a 30-day all-cause readmission rate of 17.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 16.7–18.2%), stratification revealed a higher rate for Varicose UGIB [19.6% (95% CI: 17.6–21.5%)] than for non-varicose UGIB [16.8% (95% CI: 16.0–17.5%)] .

Only a third were readmitted for recurrent UGIB (4.8% [95% CI 3.1-6.4%]). UGIB due to peptic ulcer bleeding had the lowest 30-day readmission rate [6.9% (95% CI: 3.8–10.0%)]. The certainty of the evidence was low or very low for all outcomes.

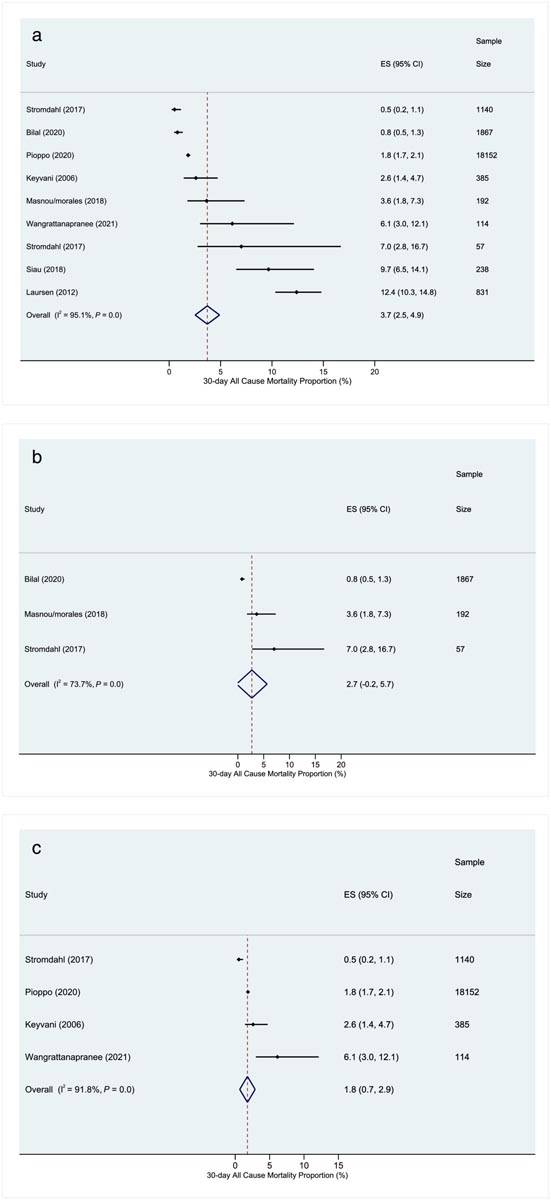

Forest plots for all-cause mortality at 30 days after hospital discharge after upper gastrointestinal bleeding. (a) All studies; (b) varicose veins; (c) without varicose veins.

Conclusions Nearly one in five patients discharged after UGIB are readmitted within 30 days. These data should prompt clinicians to reflect on their own practice to identify areas of strength or improvement. |

Discussion

Our systematic review found that almost one in five patients discharged from the hospital after an upper gastrointestinal bleed are readmitted within 30 days (17.4% [95% CI: 16.7–18.2%]). . Although high, this finding likely reflects the significant burden of comorbidity and frailty that patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AGIB) have, as opposed to poor care. Less than a third of patients readmitted in our review were due to gastrointestinal causes (such as new bleeding) (4.8% [95% CI 3.1–6.4%]).

Limited reporting limited our ability to quantify the frequencies of non-GI readmission diagnoses, however, other authors have demonstrated the association associated with other comorbidities.

Varicose HDAs (19.6% [95% CI 17.6–21.5%]) had higher rates of 30-day all-cause readmission than non-varicose HDAs (16.8% [95% CI] 16.0–17.5%.] This trend was similar for readmissions related to GI pathology. We hypothesize that similar factors that result in higher hospital deaths also increase your likelihood of being readmitted in the following 30 days, which may be partly explained by why patients with variceal bleeding have such a high rate of concomitant advanced liver disease.

We recommend physicians and institutions use the data to compare it with their own statistics and reflect on what that means for them. It may be an opportunity to identify areas for improvement or realize that your discharge strategy is successful and could be shared with others to improve your care.

Limitations

Several limitations were noted throughout the review process. Significant heterogeneity was identified in the estimation of the pooled effect; however, this was not surprising based on the use of large administrative databases and reflects the heterogeneity of the patients we care for. As discussed above, infrequent reporting of subgroup characteristics (e.g., index treatment, anticoagulation or antiplatelet status, degree of comorbidities, or gastrointestinal bleeding risk profile) limited the focus on more specific patient profiles.

There is a need to improve data in this area, as the next question that needs to be answered is which patient profiles are at higher or lower risk than the average variceal or non-variceal bleeding. Additionally, the generalizability of these results may be limited as most studies were conducted in North America.

Final message

|