Series: "Disorders that upset us in gastroenterology"

We chose this title to define a particular set of conditions that are difficult to manage. According to the Dictionary of the Royal Academy, a disorder is defined as a “mild alteration in health” and the verb to upset means “to disturb or remove tranquility or peace.” Doctors are often disturbed by these conditions that, although not serious, greatly upset the patient and represent a frequent reason for consultation. In many cases we lack an effective treatment and the literature is insufficient to help us. The purpose of this guide is to know how far we have come in the study and treatment of these disorders, what experts think and what evidence-based medicine contributes.

Series index

- oral thrush

- burning mouth

- Functional anorectal pain.

- Belching

- balloon

- Halitosis

- Prolonged hiccups

- anal itching

In each of them we will make an introduction where we will summarize the basics of current medical knowledge and the treatments usually recommended. Below, we will refer in more depth to the recommended literature and what informs evidence-based medicine when it is available.

Burning mouth syndrome: the clinical problem

Burning mouth syndrome (BQS) is a chronic oral condition characterized by a burning sensation of the oral mucosa without obvious cause. Its etiopathogenesis is obscure, but psychological and neuropathic factors seem to be involved.

There is no cure for CBBS. Treatment, whether local or systemic, is aimed at relieving symptoms and improving quality of life. In refractory cases, psychological or psychiatric intervention may be helpful.

Symptoms

The anterior part of the tongue is the most commonly affected, followed by the labial mucosa and occasionally the palate. The burning sensation is often accompanied by tingling or numbness and dry mouth. Although the oral mucosa and salivary flow are normal , 2 out of 3 patients report a decreased sense of taste and experience a bitter or metallic taste.

The burning sensation is usually symmetrical and of moderate to severe intensity; It is minimal early in the morning or during meals and generally does not disturb sleep.

Epidemiology

It affects both sexes, but is more common in women, especially postmenopausal women aged 60 and older.

It is frequently associated with stressful circumstances or an altered mood, with anxiety or depression, although it is difficult to establish to what extent the symptom is primary or secondary to the disorder.

Etiopathogenesis

In the pathogenesis of burning mouth syndrome, in addition to psychogenic factors, certain central and peripheral neuropathic alterations seem to play a role. Sometimes an undiagnosed illness causes burning mouth syndrome. In these cases it is called “secondary burning mouth”.

Secondary burning mouth syndrome Pre-existing problems that may be related to secondary burning mouth syndrome include:

|

Treatment

- Topical therapeutics

Clonazepam is a benzodiazepine that activates pain inhibitory pathways in the spinal cord and peripheral nociceptors. It has been reported that its topical use (1 to 2 drops three times a day of a 2.5 mg/ml solution) decreases the excitability of sensory nerve fibers and reduces the intensity of pain.

Capsaicin is the burning component of chili pepper and has been used topically in the treatment of BCS ; It would act through a blocking effect on substance P, which is involved in the perception of pain. However, it is not usually used due to its poor tolerance.

- Systemic therapeutics

Both clonazepam and capsaicin have been used by the digestive route. The latter less frequently due to its side effects.

Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants ( amitriptyline) have relieved symptoms in a significant number of patients.

There are several reports on the benefit of alpha lipoic acid (thioctic acid), a powerful antioxidant, in doses of 600 mg daily for 30 days, alone or associated with other treatments in the therapy of BCS.

The anticonvulsant gabapentin , commonly used in the treatment of neuropathies, was also reported as beneficial in the SBQ

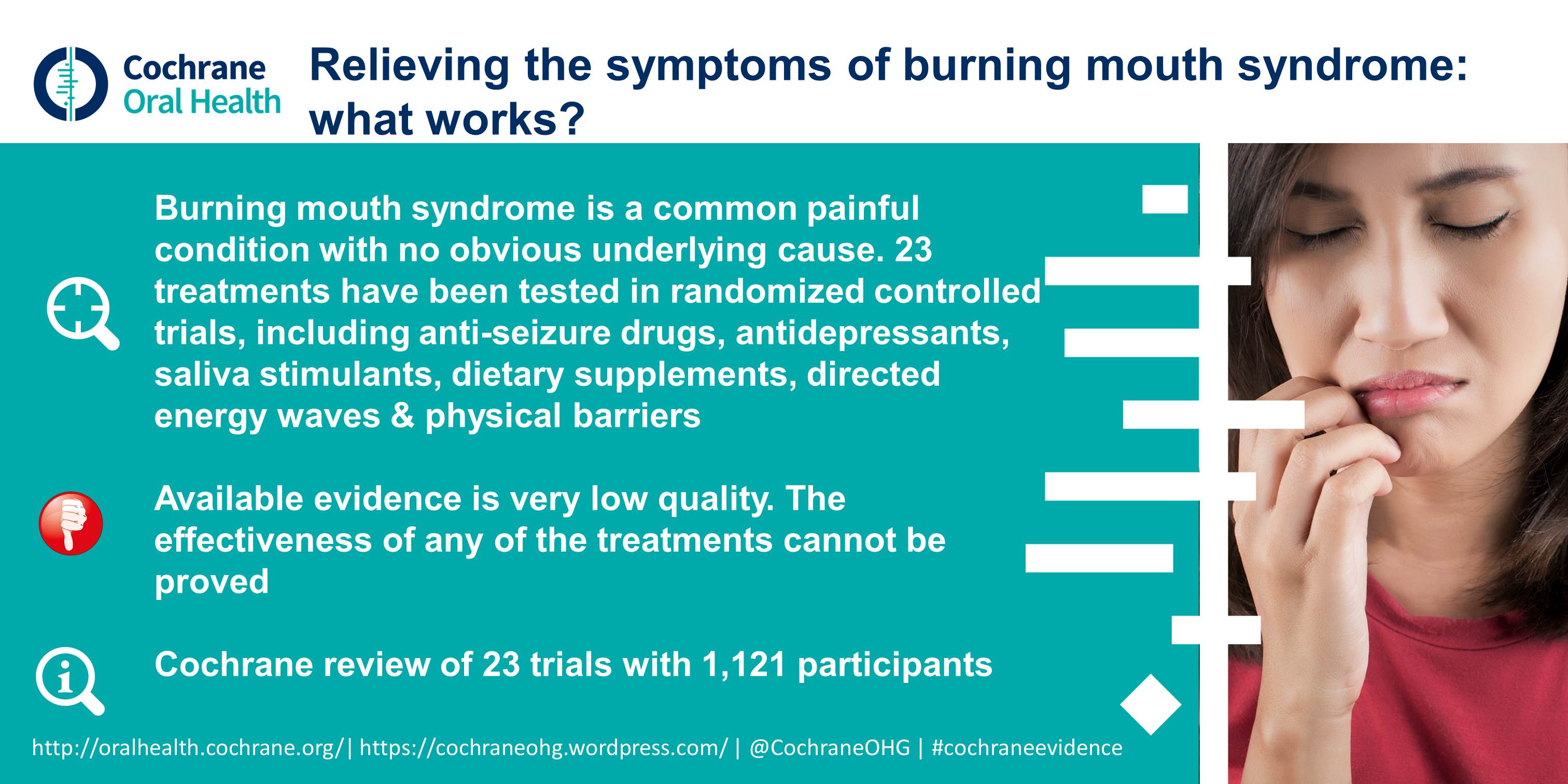

Despite the large number of treatments available, the Cochrane group report of 11/18/2016 concluded that until then there was not enough evidence to support or disapprove any of the therapies used.

Common mistakes

Sometimes some patients and also some doctors interpret that the disorder is due to gastroesophageal reflux and are treated with antacids or proton pump inhibitors to no avail.

Recommended readings

Feller, L. et al. “Burning Mouth Syndrome: Aetiopathogenesis and Principles of Management.” Pain Research & Management (2017): 1926269. PMC. Web. Mar 27, 2018