People are developing new cases of chronic pain at higher rates than new diagnoses of diabetes, depression or high blood pressure, according to a study published in JAMA New Open .

Researchers identified about 52 new cases of chronic pain per 1,000 person-years. That was higher than the rate of high blood pressure (45 new cases per 1,000 person-years) and much higher than the rates of new cases of depression and diabetes.

Of those who had no pain in 2019, 6.3% reported new chronic pain in 2020, according to the study. People often experience chronic pain in various parts of the body, but low back pain is the most common, followed by headache and neck pain.

Key points What are the incidence and persistence rates of chronic pain (pain “most days” or “every day”) and high-impact chronic pain (chronic pain that limits life or work activities most days? or every day) in US adults? Findings In this cohort study of 10,415 adult participants in the 2019-2020 National Health Interview Survey Longitudinal Cohort, the incidence rates of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain in 2020 were 52.4 cases per 1000 person-years (PY) and 12.0 cases per 1000 PY, respectively. Among adults with initial chronic pain, the rate of persistent chronic pain was 462.0 cases per 1000 PY. Meaning These longitudinal data emphasize the high disease burden of chronic pain in the US adult population and the need for early pain treatment. |

Epidemiological research on chronic pain (pain lasting ≥3 months) and high-impact chronic pain (HICP) (chronic pain associated with substantial restrictions in life activities, including work, social, and self-care activities) in the US has increased substantially since the publication of the Institute of Medicine’s (now the National Academy of Medicine’s) pain report in 2011 and the Department of Health and Human Services’ National Pain Strategy (NPS) in 2016. These papers emphasized the need for epidemiologic studies of pain in the US population, particularly in subpopulations that may be susceptible to underreporting and/or management of pain. We have not found any studies to date that examine the incidence of chronic pain in a nationally representative sample of all adults.

Importance

Estimates of prognosis and risk of chronic pain are needed to inform effective interventions.

Aim

To estimate the incidence and persistence rates of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain (HICP) in US adults across demographic groups.

Design, environment and participants

This cohort study examined a nationally representative cohort with 1 year of follow-up (mean [SD], 1.3 [0.3] years). Data from the 2019-2020 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) longitudinal cohort were used to assess chronic pain incidence rates across demographic groups. The cohort was created using cluster random probability sampling of non-institutionalized U.S. civilian adults aged 18 years or older in 2019.

Of the 21,161 baseline participants in the 2019 NHIS who were randomly chosen for follow-up, 1746 were excluded due to proxy response(s) or lack of contact information, and 334 were deceased or institutionalized. Of the remaining 19,081, the final analytical sample of 10,415 adults also participated in the NHIS 2020. Data were analyzed from January 2022 to March 2023.

Exhibitions

Self-reported sex, race, ethnicity, age, and baseline college level.

Main results and measures

Primary outcomes were incidence rates of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain (HICP), and secondary outcomes were demographic characteristics and rates across demographic groups. A validated measure of pain status, (“In the past 3 months, how often have you had pain? Would you say never, some days, most days, or every day?”) yielded 3 discrete categories each year: no pain, non-chronic pain, or chronic pain (“most days” or “every day” pain).

Chronic pain present in both years of the survey was considered persistent; IPCA was defined as chronic pain that limited life or work activities on most or all days. Rates were reported per 1000 person-years (PY) of follow-up and were age-standardized based on the 2010 US adult population.

Results

Among the 10,415 participants included in the analytical sample, 51.7% (95% CI, 50.3%-53.1%) were women, 54.0% (95% CI, 52.4%-55% .5%) were between 18 and 49 years old, 72.6% (95% CI, 70.7%-74.6%) were white, 84.5% (95% CI, 81.6% -85.3%) were non-Hispanic or Latino, and 70.5% (95% CI, 69.1%-71.9%) were non-college graduates.

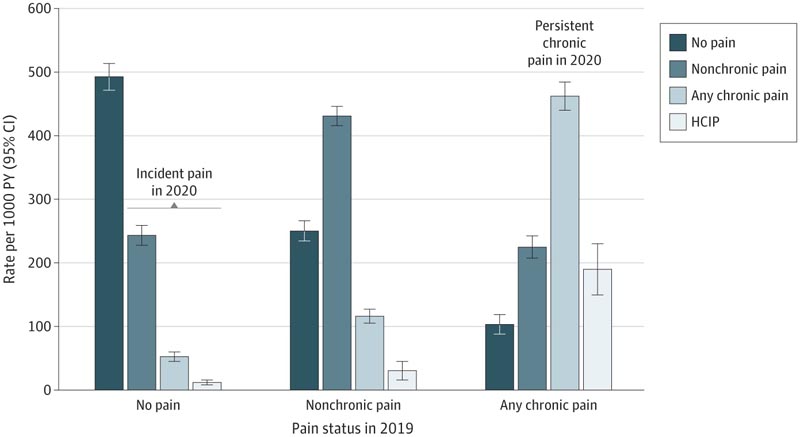

Among adults without pain in 2019, the incidence rates of chronic pain and HICP in 2020 were 52.4 (95% CI, 44.9-59.9) and 12.0 (95% CI, 8.2-15 ,8) cases per 1000 PY, respectively. The rates of persistent chronic pain and persistent HICP in 2020 were 462.0 (95% CI, 439.7-484.3) and 361.2 (95% CI, 265.6-456.8) cases per 1000 PY, respectively.

Chart: Pain rates in 2020 by pain status in 2019: No pain was defined as no pain in the last 3 months, non-chronic pain as pain on some days in the last 3 months, and chronic pain as pain on most days or every day in the last 3 months. High-impact chronic pain (HICP) was defined as chronic pain that limited life or work activities most days or every day during the past 3 months. Rates were estimated using longitudinal survey weights provided by the National Center for Health Statistics 23 (10,415 participants included in the analysis; weighted total population of 250.9 million adults whose age was standardized to the age distribution of the population of the US in 2010). Whiskers represent 95% CIs. PY indicates person-years.

Discussion

In this cohort study, nearly two-thirds (61.4%) of adults with chronic pain in 2019 continued to have chronic pain in 2020. While 14.9% of those with non-chronic pain reported chronic pain 1 year later , only 6.3% of those who were pain-free in 2019 developed incident chronic pain and only 1.4% had onset of IPCA.

Lower educational level and older age were associated with higher rates of chronic pain in 2020, regardless of pain status in 2019. Of note, the incidence of chronic pain (52.4 cases per 1000 PY) was high compared to other chronic diseases and conditions for which the incidence in the US adult population is known, including diabetes (7.1 cases per 1,000 PY), depression (15.9 cases per 1,000 PY), and hypertension (45.3 cases per 1000 PY).

Although chronic pain is sometimes assumed to persist indefinitely, our finding that 10.4% of adults with chronic pain experienced improvement over time is consistent with previous evidence from studies in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. , which revealed rates ranging from 5.4% to 8.7%. Also similar in our study and these 4 studies were the 1-year cumulative incidence rates for chronic pain at baseline, which ranged from 1.8% 30 to 8.3% 32.

The differences observed likely reflect variability in study methods, including the definition of chronic pain, populations studied, and duration of follow-up. Rates of persistent chronic pain ranged from 47.9% 30 in the youngest cohort (≥16 years of age at entry) to 93.5% 32 in the oldest cohort (≥65 years of age at entry). These rates suggest an age effect consistent with our finding that participants aged 50 years or older had a 29% higher adjusted RR of persistent pain than younger participants. Our ongoing research examines underlying factors that may explain the observed differences in chronic pain incidence, persistence, and recovery rates in our study.

Conclusions and relevance In this cohort study, the incidence of chronic pain (52.4 cases per 1,000 PY) was high compared to other chronic diseases and conditions with known incidence in the US adult population, such as diabetes, depression, and hypertension. . This comparison emphasizes the high disease burden of chronic pain in the US adult population and the need for both prevention and early treatment of pain before it becomes chronic, especially for higher risk groups. |