Many patients have been avoiding essential care during the COVID-19 disease pandemic due to fear of contracting SARS-CoV-2 infection in healthcare settings. This lack of care-seeking has been associated with an increase in mortality rates from non-COVID conditions. Some of this anxiety may have been sparked by reports of widespread outbreaks in nursing facilities and other congregate settings.

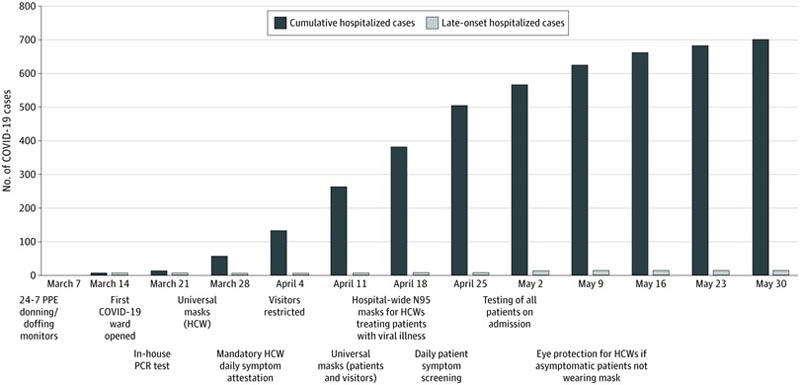

However, there is little data on the adequacy of infection control practices and the risk of acquiring COVID-19 in hospitals. During the first 12 weeks of the pandemic in the region, approximately 700 patients were admitted to Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, USA) with COVID-19 and more than 8,000 without COVID-19.

The authors reviewed all patients diagnosed with COVID-19 on or after the third day of hospitalization or within 14 days of hospital discharge to quantify the incidence of nosocomial transmission and evaluate the effectiveness of the hospital’s infection control program. .

Design, environment and participants

This cohort study included all patients admitted to Brigham and Women’s Hospital between March 7 and May 30, 2020. Follow-up was performed through June 17, 2020. Medical records of all patients were used. patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on the third day of hospitalization or later or within 14 days of hospital discharge.

Exhibitions

A comprehensive infection control program was implemented that included dedicated COVID-19 units with respiratory isolation rooms, personal protective equipment in accordance with US CDC recommendations, monitoring the donning and doffing of protective equipment. personal protection, universal masking, restriction of visits and RT-PCR tests for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

Main results and measures

Whether the infection was acquired in the community or in the hospital based on the timing of testing, clinical course, and exposures.

Results

Between March 7 and May 30, 2020, 9,149 patients (mean age 46 years; median age 51 years; 5,243 women [57.3%]) were admitted to the hospital, who underwent 7,394 RT tests -PCR for SARS-CoV-2; 697 patients were diagnosed with their first episode of COVID-19.

The COVID-19 inpatient census peaked at 171 patients on April 21, 2020. The median length of stay among COVID-19 patients was 7 days (range, 1-74 days), which is translates into 8,656 days of care related to COVID-19.

Late-onset COVID-19 cases in hospitalized patients

Of the 697 patients hospitalized with confirmed COVID-19, 12 (1.7%) were first diagnosed on or after the third day of hospitalization. The median time from admission to the first positive RT-PCR test result for these 12 patients was 4 days (range, 3-15 days).

None of the 12 patients had known exposures to staff members with COVID-19 or shared rooms with patients with confirmed COVID-19. On chart review, the infection was considered definitely community-acquired for 4 patients and probably acquired for 7.

Only 1 patient definitely acquired COVID-19 in the hospital because symptoms began on day 15 of hospitalization. This patient was most likely infected by his presymptomatic spouse who visited him daily until a COVID-19 diagnosis was made a week before the inpatient’s symptoms began. This case occurred before the implementation of visitor restrictions and universal masking of all healthcare workers and patients.

Among the 11 definite or probably community-acquired cases, factors associated with late diagnosis (on or after day 3 of hospitalization) included late suspicion because symptoms on admission were attributed to an alternative cause (2 cases); initial negative RT-PCR test results followed by positive results in serial samples from patients with high suspicion of COVID-19 (3 cases); lack of testing on admission due to absence of symptoms but with the appearance of symptoms triggering testing 1 to 2 days later (2 cases); and late onset of symptoms in patients with epidemiological risk factors who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 on admission when the virus was still in the initial incubation period (4 cases).

Late-onset hospitalized COVID-19 cases were defined as patients who first tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on or after hospital day 3. .

COVID-19 cases after discharge

Among 8,370 patients who were hospitalized with conditions unrelated to COVID-19 and discharged through June 17, 2020, 11 (0.1%) tested positive within 14 days of discharge (mean time to diagnosis, 6 days; range 1 to 14 days).

Only 1 case was considered likely hospital-acquired, although with no known in-hospital exposures. This patient had a prolonged postoperative hospitalization and developed new febrile symptoms 4 days after discharge, with no known household contacts with illness or high-risk epidemiologic factors.

Two other patients who received diagnoses shortly after discharge likely had late COVID-19 diagnoses because they had progression of the same syndromes responsible for their initial hospitalizations, but were not evaluated at initial admission; These cases occurred in March before more aggressive testing practices were instituted.

Another patient likely had false negative results during the initial hospitalization, as the patient presented to the hospital again with progression of the same syndrome that had been ongoing for 4 weeks and was diagnosed with COVID-19 based on an RT test result. -PCR.

The remaining 7 cases were likely acquired after discharge: 3 patients had high-risk exposures after discharge and 4 were discharged to skilled nursing or rehabilitation facilities with COVID-19 outbreaks.

None of the 11 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 after discharge shared a room with a patient with confirmed COVID-19. One patient received care from a staff member diagnosed with COVID-19, but also lived with a spouse who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 a week before the patient became ill.

This case was considered likely to be community acquired due to the high rate of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in households, the patient’s greater contact with the spouse than with the healthcare worker, and that universal masking of all health workers had already been implemented.

Discussion

COVID-19 presents significant challenges for infection control. A substantial proportion of patients are asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic, but highly contagious . Current diagnostic tests are imperfect, especially early in the incubation period, and patients may not develop symptoms until 14 days or more after inoculation. Furthermore, although the primary mode of transmission is thought to be through close contact and droplet exposure, infection from contaminated fomites is possible and the role of airborne transmission remains a topic of debate.

This analysis, however, revealed that a multifaceted infection control program based on US CDC guidance may be associated with minimal risk of nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

During the first 12 weeks of the pandemic in the US, this hospital cared for more than 9,000 patients, including approximately 700 with COVID-19 who were present during 8,656 days of hospitalization.

Despite the high COVID-19 burden at that hospital, the authors identified only 2 patients who likely acquired the infection in the hospital, including 1 who was likely infected by a spouse before visitation restrictions and universal masking.

The present findings differ from the results of a recent review that suggested that up to 44% of COVID-19 infections may be nosocomial. However, that review was limited to case series conducted early in the outbreak in Wuhan, China, before recognition of the virus and the institution of infection control practices and PPE.

An important theme that emerged from this case review was the need for serial testing of patients with clinical syndromes highly suspicious for COVID-19. At least 3 patients with concerning syndromes initially tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 but had positive results on repeat testing.

Other researchers have also documented that repeat RT-PCR testing can produce positive results for patients with initial negative results, although at relatively low rates. Based on initial experience, the authors instituted a protocol requiring at least 2 negative RT-PCR test results for symptomatic patients before discontinuing isolation.

Another observation that emerged was that several patients were only tested for the first time on the third day of hospitalization or later, sometimes due to atypical symptoms that were initially attributed to non-COVID conditions.

These cases highlight the importance of implementing universal testing at admission, and the authors observed fewer late-onset cases after this intervention. However, universal testing is not foolproof because several patients initially tested negative while asymptomatic and then tested positive after symptoms began several days later. This underlines the lower sensitivity of RT-PCR early in the course of infection.

Strengths and limitations

This study has strengths. This was a comprehensive analysis and review of all patients who first tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on the third day in hospital or after or within 14 days of hospital discharge. Recent national regulations only require reporting of cases diagnosed by day 14 of hospitalization or later.

Although this strategy ensures that the majority of reported cases were truly hospital acquired, it leaves hospitals blind to nosocomial infections that manifested before 14 days (which may be common because the median incubation period for SARS -CoV-2 is 5 days) or after hospitalization.

This study also has limitations.

First, it is difficult to know the source of infection in all cases.

Second, despite the implementation of aggressive testing practices, there may be additional undetected nosocomial cases related to false-negative RT-PCR test results or from patients who may have acquired an asymptomatic infection in the hospital but were never evaluated.

Third, there may be patients who were diagnosed after discharge outside the healthcare system.

Fourth, patients who developed symptoms shortly after discharge but were not tested until after 14 days may have been missed.

Fifth, these findings do not provide information on the risk of nosocomial infection among healthcare workers. The authors consider that this warrants a separate detailed analysis.

Sixth, it is not clear which of the measures implemented were most effective, particularly because policies evolved rapidly. Some measures, such as using respiratory isolation rooms for all COVID-19 patients or monitoring the donning and doffing of PPE, are not feasible in all hospitals and may not be necessary to prevent nosocomial transmission.

Seventh, there is variation in adherence to basic infection control practices across hospitals, and this may be particularly true during a pandemic because some hospitals have been overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients while others have remained within their limits. ability. Therefore, these findings may not be generalizable to all hospitals.

Conclusions These findings suggest that robust and rigorous infection control practices may be associated with minimal risk of nosocomial spread of COVID-19 to hospitalized patients. These results, especially if replicated in other hospitals, should provide peace of mind to patients as some healthcare systems reopen services and others continue to face COVID-19 surges. |