Transient ischemic attack ( TIA) is clinically described as an acute onset of focal neurological symptoms followed by complete resolution. TIA has been recognized as a risk factor for future stroke since the 1950s.

In 2009, the American Heart Association redefined TIA using a tissue -based approach (i.e. resolution of symptoms plus absence of infarction on brain imaging) instead of the time -based approach (i.e. resolution of symptoms only in 24 hours). TIA is now widely understood to be an acute neurovascular syndrome attributable to a vascular territory that resolves rapidly, leaving no evidence of tissue infarction on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DWI).

A patient with resolved symptoms and MRI demonstrating infarction should be diagnosed as an ischemic stroke (not a TIA).

| Epidemiology |

The true incidence of TIA in the United States is difficult to determine given its transient nature and the lack of standardized national surveillance systems. Furthermore, the public’s lack of recognition of symptoms suggests that many TIAs go unnoticed.

Estimates of 90-day stroke risk after TIA range from 10% to 18% and highlight the importance of rapid evaluation and initiation of secondary prevention strategies in the emergency department (ED). Like cardiovascular disease and stroke, the incidence of TIA increases with age.

| Clinical Evaluation |

Acute onset of focal neurological symptoms followed by complete resolution suggests a TIA.

Therefore, patients for whom this diagnosis is being considered should undergo a neurological examination compatible with their initial condition. Specific details of the history and presentation can help differentiate the picture from alternative diagnoses.

Nonspecific symptoms or examination findings (e.g., isolated dizziness, confusion/lethargy/encephalopathy), focal symptoms with other features (e.g., headache, seizures), or new radiological findings (e.g., lesion en masse) may suggest an alternative or "simulator" diagnosis (Table 1). In cases of diagnostic uncertainty, conventional wisdom suggests performing a neurovascular study for suspected TIA to reduce the risk of a recurrent event, ideally with expedited neurological consultation.

| Factors | AIT | AIT simulator |

| Demographics | Advanced age | Young patient without vascular risk factors |

| Medical record | Presence of vascular risk factors (high blood pressure, diabetes, coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, smoking, obesity, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, previous stroke, obstructive sleep apnea) | History of epilepsy, migraines, brain tumor |

| Symptoms | Abrupt start. Maximum symptoms at the beginning. Duration typically <60 min. Localized/focal neurological symptoms corresponding to a vascular territory: dysarthria/aphasia, facial drooping, hemiparesis, numbness of the hemibody. Dizziness combined with cranial neuropathies, vision loss/diplopia, difficulty with coordination or gait/truncal ataxia, severe nausea/vomiting may suggest a posterior circulation process. Hypertensive at presentation. Headache with ptosis and miosis may indicate dissection. | Symptoms spreading from the site of onset could suggest a seizure. Altered mentality Migraine. Presence of signs or symptoms suggesting an alternative diagnosis (i.e., positive visual phenomena, seizure-like activity, positional vertigo without localization/focal symptoms). |

Table 1. Factors suggestive of TIA versus TIA simulator. This table is intended as a guide for approaching a patient with neurological symptoms and should not be the sole determinant of the final diagnosis. Patient-specific factors must also be considered.

| Diagnostic evaluation |

> Brain imaging

The role of acute phase imaging is to rule out alternative diagnoses, assist in risk stratification, and identify potentially symptomatic lesions.

An initial non-contrast head CT scan (NCCT) is part of many stroke/TIA protocols due to its accessibility in the ED setting and is a useful test to evaluate subacute ischemia, hemorrhage, or head injury. mass. However, NCCT alone has limited utility in patients whose symptoms have resolved. Although its sensitivity for detecting an acute infarction is low, it is useful for ruling out TIA mimics.

Multimodal MRI of the brain is the preferred method for evaluating acute ischemic stroke and should ideally be obtained within 24 hours of symptom onset. In cases where MRI with DWI can be obtained without delay, NCCT can be safely avoided in a stable patient with completely resolved symptoms.

MRI with DWI demonstrates lesions in 40% of patients presenting with TIA symptoms. If a DWI-positive lesion is identified, a diagnosis of ischemic stroke is typically made, followed by hospitalization. In the clinical scenario where an acute MRI cannot be obtained to definitively distinguish TIA from stroke, it remains reasonable to make a clinical diagnosis of TIA in the ED on the basis of a negative NCCT and resolution of the symptoms within 24 hours.

> Vascular images

Evaluation of TIA requires adequate vascular imaging. Noninvasive imaging to detect carotid stenosis (or vertebral artery stenosis for patients with posterior circulation symptoms) should be a routine component of acute phase imaging. Nearly half of patients with transient neurological symptoms and DWI injuries have stenosis or occlusion of extracranial or intracranial large arteries.

Multiple non-invasive techniques are available to evaluate the cervical and intracranial carotid vasculature from the emergency department. Computed tomography angiography ( CTA) is the most accessible modality in the ED and can be obtained rapidly in conjunction with NCCT. CTA has greater sensitivity and positive predictive value than magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) for detection of intracranial stenosis and occlusion, and is recommended over time-of-flight (non-contrast) MRA. Additionally, CTA is considered safe in patients with known chronic kidney disease and is not associated with a significant risk of acute kidney injury.

Carotid duplex ultrasound and transcranial Doppler are non-contrast options to evaluate the cervical and intracranial vessels, respectively, but may not be available in the ED. Admission to a 24-hour observation or inpatient unit is usually required to obtain these studies.

> Laboratory, cardiac tests and consultation with Neurology

Point-of-care blood glucose testing should be performed for all patients with suspected TIA to rule out hypoglycemia, a known stroke mimic. A non-fasting lipid profile is acceptable to identify hyperlipidemia as a risk factor. Additionally, patients older than 50 years with visual complaints may benefit from screening with erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein to evaluate for temporal arteritis.

Telemetry, troponin testing, and electrocardiography are warranted in all patients with TIA given the shared risk factors for myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke, and for the detection of atrial fibrillation (AF).

In patients with TIA/stroke in whom a cardioembolic source is suspected , the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association recommends prolonged heart rhythm monitoring (30 days) within 6 months of the event. This can be coordinated through cardiology, vascular neurology, primary care, or, if possible, the emergency department. The role of routine transthoracic echocardiogram for patients with TIA is not well established, but is often performed to identify a source of cardiac embolism and structural abnormalities associated with the arrhythmia.

When available, a consultation with neurology (preferably vascular neurology) is a central part of the evaluation of patients with suspected TIA. Involvement of early neurology consultation has been associated with lower 90-day and 1-year mortality rates.

| Considerations for Clinical Practice |

• Non-contrast head computed tomography (NCCT) is not sensitive in ruling out small acute ischemic strokes, but may help rule out TIA mimics. • MRI with DWI is the preferred imaging modality to rule out acute infarction. If MRI with DWI can be obtained without delay for patients with TIA, NCCT can be safely avoided. • NCCT and CTA can be performed together to evaluate hemorrhage and symptomatic stenosis. • CTA is safe in patients with chronic kidney disease and the risk of acute kidney injury related to contrast administration is low. • Extended cardiac monitoring in selected patients is useful to evaluate possible sources of cardiac embolism. • Patients benefit from early neurological consultation; preferably in the ED or fast follow-up within 1 week after TIA. |

| Risk Stratification |

An ideal scale for predicting the risk of stroke after a TIA is one that is easy to calculate, has a high predictive value, can categorize patients into clinically distinct risk groups, has been validated, and has a broad ability to measure. generalization. Several TIA risk stratification instruments are available to help predict short-term stroke risk for individual patients and to guide disposition.

The most used risk stratification tool is Age, Blood Pressure, Clinical Features, Duration, and Diabetes ( ABCD2 score ). It is important to note the limitations of the ABCD2 score. First, it does not include symptoms that might suggest a “posterior circulation” process, such as dysmetria, ataxia, or homonymous hemianopsia. It also does not take into account the TIA mechanism or the presence of ipsilateral large artery stenosis on imaging and therefore should be part of a more complete evaluation.

Acute phase vessel imaging in the ED is important regardless of the ABCD2 score because it can guide immediate management. For example, in patients with suspected symptomatic cervical or intracranial stenosis, more frequent neurological monitoring, stricter blood pressure parameters to avoid hypotension, dual antiplatelet therapy, and early consultation of surgical specialties could be considered, which could prevent recurrence. early symptoms.

| Considerations for Clinical Practice |

• TIA risk stratification scales assist in the identification of high-risk patients and help guide disposition. • Given their limitations, TIA risk stratification scales should be part of a more comprehensive evaluation. • Vessel imaging in the ED is warranted regardless of ABCD2 score or likelihood of admission. |

| Patient Disposition |

Factors that affect the ability of emergency departments or medical centers to care for patients with suspected TIA include clinical expertise, tolerance for the risk of neurovascular conditions, availability of CT and MRI scans, and access to neurovascular expertise. . When there are no designated stroke centers, protocols may need to be modified.

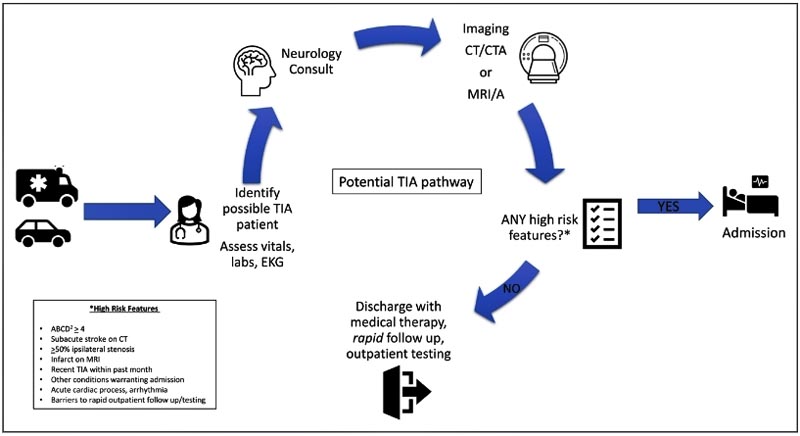

Successful DE AIT protocols include several components that may explain their effect: a clinical algorithm that allows rapid identification and diagnosis, early access to advanced diagnostic tests and imaging, risk stratification criteria (e.g., ABCD2 score), access to neurovascular experience, implementation of appropriate secondary prevention interventions and a short-term follow-up institution ( Figure 1).

Figure 1. A TIA protocol incorporating clinical assessment, imaging, and risk stratification to guide decisions. Modifications are expected when rapid neurological consultation or MRI is not available. CT indicates computed tomography; CTA, computed tomography angiography; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; and TIA, transient ischemic attack.

| Considerations for Clinical Practice |

• Presumed symptomatic (>50%) extracranial or intracranial stenoses justify hospital admission. • Acceptable disposition options include rapid protocols for TIA in the ED with referral to specialty stroke clinics, admission to a 24-hour ED observation unit, or standard hospital admission. • To determine the disposition of patients with TIA, consider the short-term risk of stroke based on the presentation and imaging of the vessels, the timeliness of a reliable diagnostic workup, the availability of prompt outpatient follow-up, and the patient’s ability to return for rapid diagnostic workup in a clinical setting. • Institutional and regional factors should guide protocols for making decisions about patient disposition. |

| Risk reduction after TIA |

Patients with TIA require immediate initiation of evidence-based interventions. The ABCD2 score can help guide appropriate treatment, and patients with higher scores are likely to benefit from dual antiplatelet therapy.

> Antithrombotics

Antithrombotic therapy is justified in all patients with suspected TIA who have no known contraindications. Short-term dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor has been shown to reduce the risk of recurrent events in selected high-risk patients with TIA presenting within 24 hours of symptom onset. For patients with TIA already receiving single-agent therapy, it is not well established whether increasing antiplatelet doses or switching to another drug confers any benefit.

Therapeutic anticoagulation is effective in reducing the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation, and evidence has shown that it can be prescribed safely from the emergency department. For patients who have TIA with known AF who have not previously received anticoagulation, it may be helpful to contact your primary care physician or cardiologist to discuss risks versus benefits.

> Statins

Statin treatment has been shown to reduce stroke recurrence in patients with ischemic stroke by 16% and has been established as a key aspect of secondary prevention. Beyond reducing low-density lipoprotein levels, statins are also beneficial for plaque stabilization, improvement of endothelial dysfunction, and inflammatory responses.

> Hypertension

Reducing blood pressure with a final ambulatory goal of <130/80 mmHg has shown a 22% reduction in the risk of recurrent stroke.

> Diabetes

Among patients with TIA or ischemic stroke, diabetes and hyperglycemia are associated with early neurological worsening and recurrence of the event.

> Behavior and lifestyle counseling

Although behavioral and lifestyle interventions that improve control of vascular risk factors may be difficult to implement after stroke/TIA, several evidence-based interventions have successfully improved counseling or control of risk factors. risky. Increasing physical activity or starting healthy diets, specifically Mediterranean-type diets or DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension), have shown reductions in stroke risk and can be successfully implemented.

> Marginalized and rural communities

Factors influencing disparities may include a focus on individual risk factors without addressing social determinants of health, such as access to transportation, fewer primary care physicians in both rural and high-risk areas, and high costs of attention.

> Education required: signs and symptoms of stroke

It is essential to develop consistent and innovative approaches to providing education to TIA patients and their families in the ED. Multilingual educational materials should be provided on signs and symptoms of stroke, when to return for emergency care, the time sensitivity of treatment options, and understanding the importance of secondary prevention treatments.

| Considerations for Clinical Practice |

• Maximal medical therapy includes antithrombotic therapy along with blood pressure, glucose, and lipid control with goals that adhere to established guidelines. • The ABCD2 score can be used to guide antithrombotic regimens. • Counseling combined with medical management may be helpful for patients with substance use disorders. • Attention to the social determinants of health can help address health disparities. |

| Follow-up appointments |

Considering the subsequent risk of recurrent stroke after TIA, prompt follow-up with a neurologist and primary care physician is warranted. One study found a significant reduction in 90-day stroke risk when the time from TIA to stroke specialist review changed from 3 days to 1 day (10.3% to 2.1%, respectively). ).

| Conclusions |

TIA is a strong predictor of future stroke and requires careful evaluation to adequately identify high-risk patients.

Several tools are available to assist in the evaluation of patients with suspected TIA, including risk stratification scales, acute phase imaging, and neurological consultation. Incorporating these steps into a clinical pathway can facilitate appropriate patient disposition, such as hospital admission for those at highest risk, while reducing unnecessary hospitalizations for those with a better prognosis.

Implementation of patient-specific secondary prevention strategies is essential to prevent future events. It is up to each center to use available resources and create a path to ensure successful management and disposition of TIA patients.