| 1. Introduction |

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), formerly known as Horton’s disease or temporal arteritis, is the most common vasculitis affecting people over 50 years of age. GCA is characterized by granulomatous inflammation that affects medium- and large-caliber arteries, causing acute and chronic damage. In addition to the clear association with advanced age, other factors have been described, such as genetic variants in the major histocompatibility complex region.

New onset headache , reflecting involvement of the temporal arteries and their branches, is the prototypical manifestation of GCA, along with increased serum acute phase reactants.

In this scenario, permanent vision loss is the most feared complication. In recent decades, the classic GCA paradigm has progressively evolved towards a more complete model that encompasses inflammation of both cranial (C-GCA) and extracranial (great vessels, GV-GCA) arteries.

This scenario is further complicated by the strong association between GCA and polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), an inflammatory disorder affecting periarticular structures with similar epidemiological characteristics. In fact, cases of steroid-refractory PMR have been described as the only presenting feature of GV-ACG, and evidence of subclinical inflammation in the temporal arteries has been found in patients with PMR without overt clinical evidence of GCA.

The GCA diagnostic algorithm has also progressed significantly. Although temporal artery biopsy (TAB) has historically represented the only tool, in recent years non-invasive confirmation of GCA by means of vascular imaging has become more common.

Glucocorticoids still represent the mainstay of GCA treatment, however inhibition of interleukin (IL-) 6 has become a fundamental therapeutic option after the demonstration of the notable efficacy of tocilizumab. Promising new drugs are being investigated that will hopefully strengthen the GCA therapeutic arsenal in the coming years.

The objective of this review is to highlight the existing knowledge on the diagnosis and treatment of GCA, with a specific focus on the innovations that marked more recent years.

2. Diagnosis

2.1. Clinical features

The clinical spectrum of GCA is broad and ranges from classic cranial symptoms to nonspecific constitutional manifestations. It is essential to limit delays in diagnosis, as GCA can cause acute and irreversible ischemic complications.

2.1.1. Cranial symptoms

New-onset, persistent headache is the most common presenting symptom, occurring in more than two-thirds of patients.

Involvement of the cranial arteries can also cause scalp tenderness, dysphagia, and claudication of the jaw and tongue.

In patients with cranial GCA, physical examination may reveal abnormalities of the temporal artery, including prominence, tenderness, and lack of pulse. Attention should also be paid to the occipital and facial arteries, as they may also be enlarged or tender. However, a normal appearance of the temporal arteries does not rule out a diagnosis of GCA.

Visual symptoms are the most feared clinical manifestation of GCA, as they could herald the development of irreversible ischemic complications. Patients may report an abrupt, self-limiting partial defect in the field of vision (amaurosis fugax) or diplopia, which is highly specific for GCA. If left untreated, these symptoms can progress to irreversible vision loss.

The most common mechanism underlying vision loss is arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION), sustained by inflammatory occlusion of the posterior ciliary artery, a branch of the ophthalmic artery.

2.1.2. Systemic and vascular manifestations

Low-grade fever may be present in more than half of GCA patients, while a body temperature above 39ºC is not typical and should guide towards alternative diagnoses.

It should be noted that GCA is one of the most common causes of fever of unknown origin in the elderly.

A higher prevalence of systemic symptoms has been reported in patients with extracranial involvement. Therefore, when these manifestations prevail, the extracranial arteries should be investigated regardless of the presence of cranial symptoms.

Vasculitis of the aorta and its branches may also cause vascular symptoms that resemble those most commonly reported by patients with Takayasu arteritis. The most typical are arteriodynia, a burning pain over the area of an inflamed artery (eg, carotidnia), and extremity claudication, an ischemic pain caused by acute or chronic stenosis of an artery in the extremities.

2.1.3. Polymyalgia rheumatica

PMR is an inflammatory condition characterized by the abrupt onset of symmetrical pain and stiffness in the neck and shoulder and hip girdles. Functional limitation is usually present, especially in the morning, and significantly impacts daily activities.

Approximately 50% of GCA patients simultaneously show features of PMR. In contrast, up to 20% of patients diagnosed with PMR develop GCA. To avoid delays in diagnosis, special attention should be paid to patients with PMR who report symptoms compatible with GCA. Identification of large vessel involvement in these cases is essential since the initial dose of glucocorticoids required for the management of GCA is higher.

2.2. Laboratory Features

Since GCA is a systemic inflammatory disease, laboratory tests represent a useful aid in the evaluation of new patients. The increase in classic acute phase reactants is a key element that accompanies the onset of GCA. On the contrary, normal levels do not definitively rule it out, but should raise suspicion of alternative diagnoses. In recent years, new disease biomarkers have been identified that possibly aid in the diagnosis of GCA and the detection of disease relapse.

2.2.1. Classic biomarkers

Classic inflammatory markers are C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

If performed in the appropriate context, elevated levels of these biomarkers have a high sensitivity for a diagnosis of GCA, as they can be found within normal limits in less than 5% of patients.

Systemic inflammation is also associated with an increase in plasma fibrinogen values and alpha-2 fraction on serum protein electrophoresis, and these two biomarkers also correlate with disease activity.

2.2.2. New biomarkers

IL-6 plays a prominent role in the pathogenesis of GCA and an increase in its serum levels was associated with an increased risk of future relapses in a study evaluating patients treated with tocilizumab. However, there is no definitive evidence that IL-6 levels correlate with disease activity. Furthermore, its measurement is expensive and not available everywhere.

Osteopontin is a glycoprotein that participates in several inflammatory pathways and is highly expressed in tissue biopsies from patients with GCA. Serum levels of this biomarker are significantly higher in patients with active disease and are not modified by tocilizumab. Furthermore, serum calprotectin correlates with disease activity in GCA patients on glucocorticoid treatment and possibly maintains such a predictive role also during IL-6 blockade therapy.

Antibodies against human ferritin peptide have also been shown to be present in more than 90% of patients with active GCA, making it a potentially useful diagnostic marker. Although all of these new biomarkers seem promising, more studies are needed to evaluate their reliability and their application in daily clinical practice.

23. Temporal artery biopsy

For decades, arterial biopsy has represented the only tool available for confirming the diagnosis of GCA.

In fact, performing a biopsy allows us to obtain histological evidence of the inflammatory processes that characterize this pathology. The procedure is almost always performed in the superficial temporal artery, since this site is easily accessible and its removal has minimal consequences.

2.3.1. Diagnostic performance

TAB has a high specificity for the diagnosis of GCA (up to 100%). However, its sensitivity is much lower. The main causes beyond a false negative BAT result are poor sampling and the segmented nature of inflammation in vascular lesions.

If clinical suspicion of GCA is high, steroid therapy should never be delayed for BAT. However, it should be obtained within four weeks of starting treatment, as high doses of glucocorticoids may lead to progressive resolution of the vascular inflammatory infiltrate.

2.3.2. Histological findings

In arteries affected by GCA, a transmural mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, macrophages, and giant cells is typically found. A thicker inflammatory tissue surrounding the external elastic lamina and a thinner inflammatory component along the internal elastic lamina give the vessel a characteristic "concentric rings" appearance.

The clinical impact of different patterns of lymphocyte infiltration is being considered. It appears that Th1-dependent inflammation may respond poorly to glucocorticoids and could be associated with a more relapsing phenotype. Therefore, early introduction of steroid-sparing agents could be beneficial when Th1 cells represent the predominant histological feature.

2.4. Images

Nowadays, imaging techniques are essential in the diagnosis of GCA. They should always be interpreted in the context of clinical and laboratory findings to avoid incorrect diagnoses. On the other hand, its role in monitoring patients after the start of therapy and in defining disease activity is not yet fully clarified.

2.4.1. Color Doppler Artery Ultrasound

The role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of GCA was first demonstrated in 1997, when the presence of a characteristic noncompressible hypoechoic halo ( "halo sign" ) was noted around the temporal arteries in a patient with new disease. appearance. This circumferential area around the vascular lumen is thought to represent mural edema.

The presence of the bilateral halo sign of the temporal arteries is very specific for GCA, as is its persistent visibility during compression by the ultrasound probe (“compression sign”).

In the last decade, ultrasound has become widely available and is now accepted as a diagnostic surrogate for BAT, provided it is performed by an experienced clinician. Current European guidelines suggest that ultrasound should be chosen as the first diagnostic test at the onset of the disease, due to its low invasiveness and rapid availability of results.

Ultrasound has also been validated for the purpose of monitoring patients and evaluating response to treatment. A recent prospective study has shown that the halo sign correlates with markers of disease activity and cumulative glucocorticoid dose. Furthermore, it is present in more than 90% with relapses of the disease.

2.4.2. [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

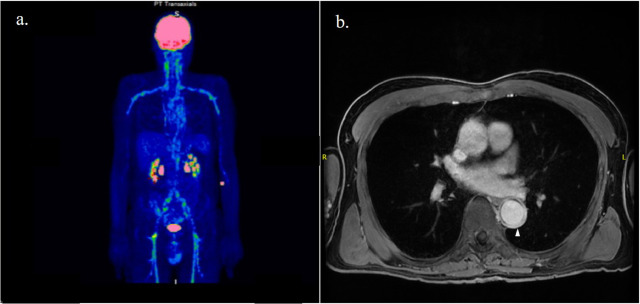

In recent years, the use of FDG-PET/CT has gained greater importance in the diagnosis of GCA, as it helps rule out alternative diagnoses and detect the presence of extracranial artery involvement. Extracranial arteritis generally encompasses diffuse inflammation of the aorta and its branches, which are often involved bilaterally. ( Figure 1a ). Compared with Takayasu arteritis, inflammation of the mesenteric and renal arteries is exceptional, while the axillary arteries are most frequently affected.

Current guidelines suggest requesting FDG-PET/CT in patients with symptoms suggestive of extracranial arteritis . Of note, patients with GV-ACG may present without cranial involvement (i.e., absence of cranial symptoms and negative US/TAB). In these cases, whole-body imaging studies (i.e., FDG-PET/CT, CTA, and MRA) are the only tests that can identify vasculitic lesions.

Although the sensitivity of FDG-PET/CT in detecting inflammation of extracranial arteries is high within the first three days after initiation of glucocorticoids, it decreases significantly in the following weeks. To retain the diagnostic power of FDG-PET/CT, this imaging study should be performed soon after initiation of therapy.

2.4.3. Magnetic resonance angiography and computed tomography

CTA is a widespread and readily available technique. Active vasculitis is shown by wall thickening and increased mural contrast enhancement. Additionally, CTA may show morphologic abnormalities such as stenosis and aneurysms. However, CTA is not recommended to study cranial arteries due to the lack of evidence in this regard. Additionally, it is associated with significant radiation exposure and requires a potentially nephrotoxic contrast medium.

MRA is a non-radiative technique that also allows the detection of arterial inflammation and luminal changes. As in CTA, enhancement and wall thickening with gadolinium contrast are signs of vessel inflammation ( Figure 1b ). This approach is recommended if ultrasound is not available or inconclusive.

The combined use of FDG-PET/CT and MRA or CTA is particularly useful as it allows a quantitative analysis of inflammation to be combined with the morphological characterization of the vessels. The presence of contrast enhancement in metabolically active vessels corroborates the diagnosis of vasculitis and rules out alternative causes of uptake (eg, atherosclerosis).

Figure 1. Patient affected by giant cell arteritis with involvement of the aorta and its branches as shown by contrast enhancement on positron emission tomography with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose ( a ) and wall thickening (tip of arrow) on magnetic resonance angiography scans ( b ).

3. Treatment

The treatment of GCA has three main objectives: i) dampen the disturbed inflammatory process to avoid acute ischemic complications; ii) prevent disease relapses by using the lowest effective dose (if any) of glucocorticoids; iii) prevent long-term vascular damage (i.e. aneurysm and stenosis). Glucocorticoids remain the mainstay of GCA treatment. However, the addition of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) may be necessary to obtain and maintain disease remission in selected cases.

3.1. Glucocorticoids

High-dose systemic glucocorticoids should be initiated once the diagnosis of GCA is suspected to prevent ischemic complications.

Imaging and histologic studies should be obtained as soon as possible, but should never delay glucocorticoid administration.

Current European guidelines recommend a starting dose of 1 mg/kg per day of prednisone equivalent, not exceeding a daily dose of 60 mg as there is no evidence to suggest additional benefit. If there is transient or permanent visual loss, intravenous pulses of methylprednisolone (0.25 to 1 g for up to three days) may be administered before starting oral glucocorticoids to prevent progression of damage or contralateral involvement. However, once fully established, vision loss is rarely reversible, regardless of the route of administration.

While reducing the glucocorticoid dose, clinical monitoring and serial measurement of acute phase reactants are essential to identify disease relapses. If a flare is diagnosed, glucocorticoids should be increased to the last effective dose or, in case of ischemic manifestations, to the induction dose.

The risks associated with the prolonged use of glucocorticoids at moderate-high doses are especially accentuated in patients with GCA due to the advanced age of this population. They include osteoporosis and osteoporosis-related bone fractures, common opportunistic infections, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

3.2. Steroid sparing agents

The addition of a non-steroidal immunosuppressive agent may be required in some selected patients with GCA. According to European guidelines, patients eligible for adjunctive therapy are those with recalcitrant disease (i.e., relapses are observed when tapering glucocorticoids) or when risk factors for steroid-related complications are present.

3.2.1. Conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

Overall, trials evaluating this adjunctive treatment support its effectiveness in reducing cumulative glucocorticoid dose and relapse rate. Current European guidelines recommend methotrexate as an alternative to tocilizumab. The minimum recommended dose is 15 mg per week.

3.2.2. Biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

Tocilizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets the IL-6 receptor and exerts notable anti-inflammatory effects. It can be administered subcutaneously (at a weekly dose of 162 mg) or intravenously (at a monthly dose of 8 mg/kg). In patients with GCA, the addition of tocilizumab leads to higher remission rates than glucocorticoid monotherapy, even when glucocorticoids are tapered according to an accelerated regimen (i.e., within six months).

The optimal duration of tocilizumab treatment is currently unknown. Abrupt discontinuation after one year is associated with a 50% relapse rate. Therefore, most patients may merit longer treatment, perhaps at lower doses.

4. Relapses and long-term complications

Although the response to glucocorticoids is usually satisfactory, GCA relapses during and after tapering of treatment. GCA relapses range from subclinical inflammation that can only be detected with laboratory tests and imaging to clinically evident manifestations.

When a relapse is diagnosed, glucocorticoids should be increased to the last effective dose or, in case of ischemic manifestations, to the induction dose. It is also recommended to start DMARDs in this case to prevent new outbreaks of the disease and reduce the cumulative dose of steroids.

In addition to the imminent risk of vascular complications such as blindness and stroke, GCA also encompasses long-term complications such as aneurysms and vessel stenosis. Aortic aneurysms can complicate the history of patients with GCA in up to 20% of cases. Unlike atherosclerosis-related aneurysms, GCA-related aneurysms are more commonly seen in the thoracic aorta than in the abdominal tract.

5. Conclusions In recent decades, the spectrum of GCA has expanded beyond mere inflammation of the cranial vessels. This condition can now be considered a multifaceted vasculitic syndrome. Although GCA can cause significant morbidity due to acute and chronic vascular damage, the diagnostic approach to this disease has improved markedly in recent years. The introduction of tocilizumab into the therapeutic algorithm considerably increased the chances of controlling disease activity in the majority of patients. However, some questions about the pathogenesis and natural history of GCA remain unresolved and require further investigation. Once clarified, these aspects will improve the clinical management and prognosis of patients affected by this disease. Each new patient with suspected new-onset GCA should undergo appropriate staging, using the different imaging techniques available, to establish the extent of the disease (e.g., cranial vs extracranial GCA +/- PMR). Based on existing data, it is considered that the management of patients with cranial and extracranial GCA should follow different paths. The first group may merit higher initial doses of glucocorticoids and may benefit from glucocorticoid monotherapy, at least in the early stages. On the contrary, in patients with extracranial disease, the introduction of a steroid-sparing agent should be sought from the outset to reduce the frequency of flares. Tocilizumab should always be the preferred antirheumatic agent, if not contraindicated, as its use is based on the most robust data. However, there is a lot of reliance on new drugs currently being investigated, such as secukinumab and JAK inhibitors. |