Obesity is independently associated with an increased risk of heart failure, atrial fibrillation (AF), and thromboembolic events.

Obesity is generally associated with cardiac remodeling characterized by left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy. Recent evidence suggests that obesity appears to be related to myopathic changes in the left atrium (LA) (in terms of LA dilation and dysfunction9). This is relevant as compelling evidence now shows that LA dilation and dysfunction (e.g., lower LA reservoir function, a marker of reduced LA compliance) are associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes.

To date, it is unclear whether LA myopathy in obesity may be a downstream phenotype reflecting the increased burden of cardiovascular risk factors caused by obesity (e.g., type 2 diabetes and hypertension) or whether myopathic changes are present. early in AL (i.e., onset before the cardiovascular complications of obesity occur) likely reflecting the systemic inflammation and hemodynamic stress15 associated with this condition.

Although Mendelian randomization studies have confirmed that a high body mass index (BMI) is causally related to atrial fibrillation (sometimes considered an extreme form of atrial myopathy), it is unclear whether a weight loss intervention (already either through dietary intervention or bariatric surgery) would be sufficient to reverse the myopathic LA phenotype.

Here, we use advanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) to evaluate (a) whether obesity is associated with LA dilation and dysfunction in people without established cardiovascular disease, and (b) whether any degree of weight loss improves dilation and function of the LA in these subjects.

Background

Obesity is associated with left atrial (LA) remodeling (i.e., dilation and dysfunction), which is an independent determinant of future cardiovascular events. Our objective was to evaluate whether LA remodeling is present in obesity even in people without established cardiovascular disease and whether it can be improved by intentional weight loss.

Methods and Results

Forty-five severely obese individuals without established cardiovascular disease (age, 45±11 years; body mass index; 39.1±6.7 kg/m2; excess body weight, 51±18 kg) underwent MRI. cardiac analysis for quantification of AI and left ventricular size and function before and at a median of 373 days after a low glycemic index diet (n=28) or bariatric surgery (n=17).

The results were compared with those obtained in 27 normal weight controls with similar age and sex. At baseline, people with obesity showed reduced LA reservoir function (a marker of atrial compliance) and higher LA mass and peak volume (all controls P<0.05) but lower LA emptying fraction. normal.

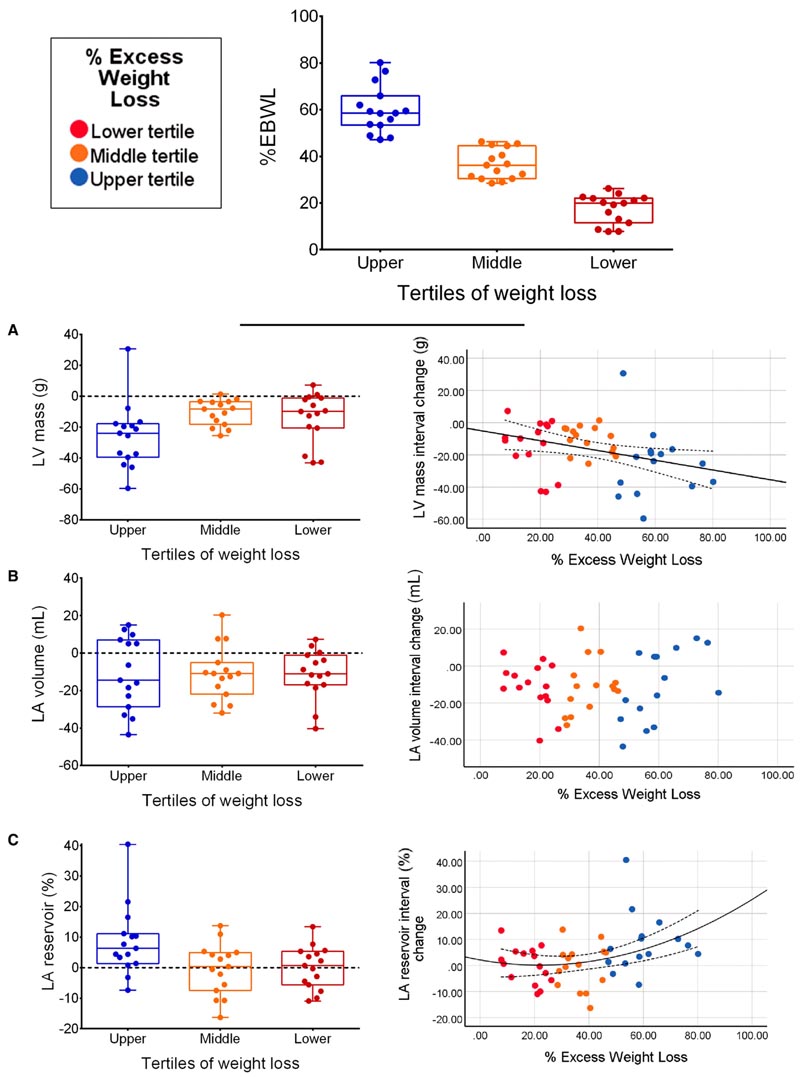

On average, weight loss led to a significant reduction in peak LA volume and left ventricular mass (both P < 0.01); however, significant improvement in LA reservoir function was only observed in those in the top tertile of weight loss (≥47% excess body weight loss).

After weight loss, we found a mean residual increase in left ventricular mass compared with controls, but no significant residual differences in peak LA volume and strain function (all P>0.05).

Effects of intentional weight loss levels on cardiac parameters. Weight loss levels were calculated as tertiles of percent excess body weight loss and a color-coded legend was also reported. Also shown are changes in left ventricular mass (A), maximum left atrial volume (B), and left atrial reservoir tension (C) stratified for different levels of weight loss (i.e., tertiles). of excess body weight percentage loss), as well as the correlation between the percentage loss of excess body weight and cardiac parameters. Comparisons of changes in cardiac parameters between weight loss tertiles are reported in Table S1. Left ventricular mass changes linearly with changes in percent excess body weight loss (A, y=−5.17−0.3*x) while left atrial reservoir strain changes quadratically (C, y=−0.074* x+0.003*x*x). The overall population of 45 participants is stratified by weight loss tertile with 15 individuals within each tertile. LA indicates left atrium; and LV, left ventricle.

Conclusions

Obesity is associated with subtle LA myopathy in the absence of overt cardiovascular disease. Only large volumes of weight loss can completely reverse the myopathic LA phenotype.

Clinical Perspective What’s new? Subtle left atrial dysfunction may be found in individuals affected by obesity, even in the absence of overt cardiovascular disease and risk factors. The left atrial myopathic phenotype can be completely reversed with large volumes of weight loss. What are the clinical implications? When treating people with obesity, efforts to obtain large volumes of weight loss may be considered to reverse early subtle left atrial dysfunction, even in the absence of overt cardiovascular disease and risk factors. |