Background

The consumption of alcoholic beverages is as old as human history, dating back to early civilizations such as ancient Egypt and ancient China. The distillation of alcohol can be attributed to the early scientists of the Islamic world. Alcoholic beverages containing ethanol are one of the most used and accepted recreational drugs worldwide. Excessive consumption of alcoholic beverages has negative medical and social consequences.

However, some people can suffer these consequences without consuming alcohol.

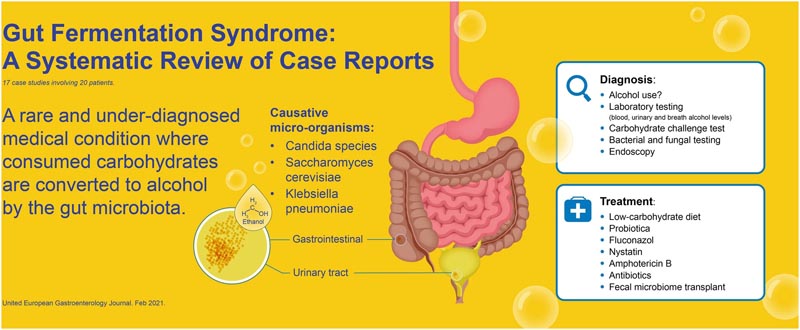

These unfortunate individuals suffer from the so-called gut fermentation syndrome (GFS), also known as endogenous alcoholic fermentation syndrome, gut fermentation syndrome or self-brewery syndrome . We suggest referring to this disease as intestinal fermentation syndrome in future literature.

GFS is a rare and under-recognized medical condition. Consumed carbohydrates are metabolized to alcohol by fungi and/or bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract. Fungi are not commonly present in the upper gastrointestinal tract, but may be present in the colon as part of the commensal microbiome.

Some fungi are known to produce ethanol, such as fungi of the genera Candida and Saccharomyces. Recently, the role of bacteria such as Klebsiella and Escherichia in intestinal alcohol production has also become evident.

It is a rare and underdiagnosed medical condition in which consumed carbohydrates are converted to alcohol by the microbiota in the gastrointestinal or urinary tract.

GFS symptoms can have a severe impact on patients’ well-being and can have social and legal consequences.

The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the evidence of FSGS, causative microorganisms, diagnoses and possible treatments.

Methods

A protocol was developed before the start of the systematic review (PROSPERO 207182).

We conducted a literature search for clinical studies on September 1, 2020 using PubMed and Embase. All clinical studies, including case reports describing FSGS, were included.

Results

In total, 17 case reports were included, consisting of 20 patients diagnosed with FSGS. Species causing GFS included Klebsiella pneumoniae, Candida albicans, C. glabrata, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, C. intermedia, C. parapsilosis, and C. kefyr.

Overview of intestinal fermentation syndrome. The highlighted microorganisms were not described in the case reports, but are known in the literature for their ability to produce ethanol.

Clinical features

Patients described in the included case reports had various initial symptoms at the time of presentation. These symptoms include: difficulty speaking (n = 5), fruity breath odor (n = 3), difficulty walking (n = 5), episodes of depression (n = 2), seizures (n = 2), vomiting ( n = 4), feeling of intoxication (n = 7) and disorientation (n = 3).

Two cases had elevated liver function tests. Two case reports came to light during breathalyzer testing , one of which was after an accident. Eight cases were initially suspected of GAS as the main working diagnosis.

The median age of the patients was 44 years (range: 3-71) and 14 patients were men (70%). In 11 of the 20 case reports, the patient had comorbidities. Comorbidities included short bowel syndrome (n = 3), diabetes mellitus type (n = 4), hypertension (n = 3), liver cirrhosis (n = 1), and Crohn’s disease (n = 1).

Kruckenberg et al.14 described a patient who suffered from urinary FSGS . This variant of FSGS was caused by chronic glycosuria and colonization of the urinary tract by C. glabrata and S. cerevisiae. This patient was difficult to treat due to persistent glycosuria.

Another comorbidity described is short bowel syndrome. Stagnation of digested food in the short intestine can cause favorable conditions for the growth of fungi and bacteria.

Recent studies also found changes associated with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.

Diagnostic evaluation

The complete evaluation of FSGS includes a history, physical examination, laboratory tests, stool specimen with culture, a carbohydrate challenge test , and endoscopy with biopsies for culture.

Evaluation of patients should consist of a complete history, including antibiotic use, alcohol intake, and unexplained episodes of intoxication. A general physical examination should have followed a neurological examination. On examination, special attention should be paid to signs of hepatic abnormalities (e.g., liver enlargement, jaundice, spider nevi) and neurological deficits (e.g., slurred speech and difficulty walking) consistent with poisoning. alcohol.

Laboratory tests include complete blood count, electrolytes (sodium, potassium), kidney function tests (creatinine, blood urea nitrogen), liver function tests (alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin), endocrine functions (glucose, blood-stimulating hormone). thyroid) and vitamin status (especially vitamin B1 and B12).

A stool test may be used for fungal or bacterial growth. To diagnose FSGS, a carbohydrate challenge of 100 to 200 g of glucose combined with blood alcohol concentration (BAC) and breath or plasma alcohol testing at intervals of 0, 4, 8, 16 and 24 hours The measurement should be performed before glucose is administered. It is important that patients be strictly monitored during the test for any consumption of alcoholic beverages , which would otherwise severely bias the test.

An upper and lower gastrointestinal tract endoscopy may be used to collect gastrointestinal secretions and biopsies for fungal and bacterial testing. These fungi and bacteria can be tested for sensitivity to antibiotics and antifungals.

The diagnosis of FSGS can be made when the carbohydrate challenge test is positive and a causative organism has been cultured and all other causes of symptoms have been excluded.

Treatment options

In five case reports, fluconazole 100 mg/day for 3 weeks and/or a low-carbohydrate diet was sufficient to treat FSGS.

However, in some patients it was necessary to switch to other medications because fluconazole was ineffective. These other treatments included nystatin, amphotericin, micafungin, itraconazole, voriconazole, metronidazole, or combinations thereof.

Fluconazole has been used empirically in some cases as a treatment for FSGS; however, it would be more ideal to treat patients based on antibiotic and antifungal susceptibility testing.

Furthermore, one study described the successful treatment of FSGS with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) after all other therapies had failed.

Clinical implications

Doctors should be aware of this rare but unpleasant diagnosis . As shown in some of the case reports, patients were misdiagnosed as alcohol users. Some even received psychiatric treatment for detoxification, which was unsuccessful.

Clinicians should be especially alert if a patient was previously treated with antibiotics and presents with symptoms of alcohol poisoning but denies any use.

This also differentiates between patients with FSGS and people who consumed alcohol excessively. People who consumed too much alcohol would not have an increase in ethanol level after the carbohydrate challenge.

Fluconazole combined with a low-carbohydrate diet was effective in five case reports; however, some patients required additional antifungal treatment. The decision for antifungal or antibiotic treatment should be based on the cultured microorganism, preferably based on susceptibility testing.

Legal implications

In two case reports, abnormally high blood ethanol levels had legal consequences for the patient. Excessive use of alcohol while driving is legally prohibited worldwide. Legal consequences range from a financial fine to imprisonment when the death occurred during a car accident. Patients with GFS may cause a car accident or be found to have high levels of ethanol during routine breath alcohol screening, without consuming alcohol.

Recently, in the Netherlands, a male patient diagnosed with FSGS was acquitted of charges after he caused an accident while intoxicated by endogenous ethanol without having consumed alcohol. This emphasizes the importance of early recognition of this rare condition.

This is important to consider in legal cases. Doctors should take patients with unexplained poisoning episodes seriously, and that could prevent patients from causing (fatal) car accidents.

Conclusions FSGS is a rare and often misunderstood and unrecognized condition that doctors should consider or be aware of. The literature is only made up of case reports, there have been no high-level evidence studies regarding prevalence and treatment. The disease is mainly caused by the genera Saccharomyces and Candida, and some cases were previously treated with antibiotics. In some case reports, risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, and previous intestinal operations have been identified. The diagnosis can be made by an appropriate history and a carbohydrate challenge test. Current treatments include antifungal medications, low-carbohydrate diet , and probiotics. There could be a potential role of fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of FSGS. Low-grade FSGS should also be considered and studied in NASH. |