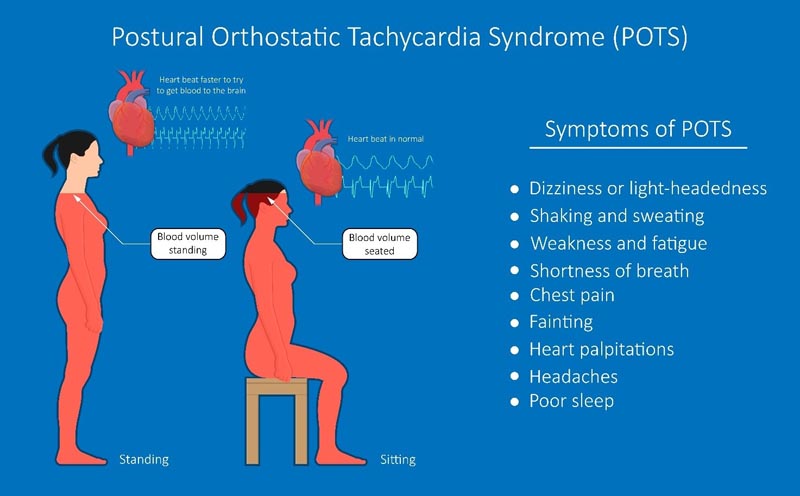

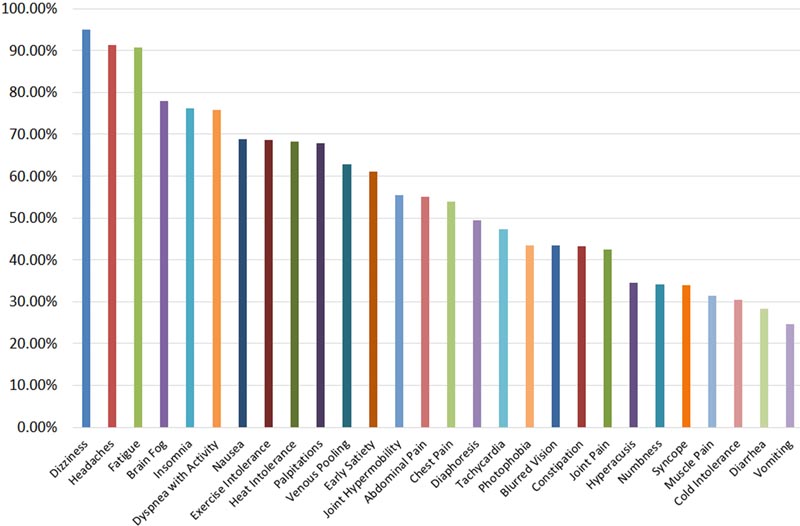

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a dysautonomia that has only been recognized in the last 30 years. Common symptoms include dizziness, headaches, fatigue, mental confusion, and insomnia , but many other symptoms have been reported. The symptoms are often quite debilitating.

Because symptoms can be quite varied and many doctors are not yet familiar with POTS, patients may present with symptoms for months and years before a diagnosis is made. Additionally, because there is still much that is unclear about the etiology and pathophysiology, many patients, families, and physicians are frustrated with treatment options for POTS.

This week, Pediatrics publishes a cutting-edge review article, titled "Pediatric Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: Where We Stand ," by Dr. Jeffrey Boris and Dr. Jeffrey Moak, both pediatric cardiologists with extensive experience working with patients with POTS .

This article is a must read for all clinicians who care for children and adolescents. There is a lot to review: diagnostic criteria, risk factors, neurohormonal and hemodynamic abnormalities, clinical evaluation, and clinical management.

It is an article that can be shared with patients and their families. A good number of these patients will have experienced feelings of "Is this all in my head?" , and you will gain comfort and reassurance from this article that clearly refutes that notion.

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), first described in 1992, remains an enigmatic , albeit variably severe and debilitating disorder. The pathophysiology of this syndrome is not yet understood and there is no remaining biomarker that indicates the presence of POTS. Although research interest has increased in recent years, there are relatively fewer clinical and research studies addressing POTS in children and adolescents compared to adults. However, it is in adolescence when a large number of POTS cases begin, even among adult patients who are studied later.

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), a dysautonomia affecting multiple somatic systems in children and adults, causes significant disability. POTS has been increasingly recognized since it was first reported in 1992 with an increasing number of publications since the late 1990s.

Its relatively high morbidity, in addition to relatively low research funding, led the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) to sponsor a seminar where international POTS experts met to discuss the state of the science and priorities for investigation.

This paper will examine several characteristics regarding the diagnostic and clinical aspects of POTS in children and adolescents and summarize specific research findings within these groups.

Diagnostic criteria

- Patients may have numerous symptoms in multiple body systems.

- POTS predominantly affects white women in the United States.

Diagnostic criteria for pediatric POTS include symptoms of chronic orthostatic intolerance for ≥3 months, persistent symptomatic increase in heart rate by ≥40 beats per minute in the first 10 minutes of upright position after supine without orthostatic hypotension , and the absence of other possible etiologies. Heart rate criteria may be questioned.

When considering clinical disorders spanning the pediatric and adult age range, it is tempting to contemplate similarities, consider general pathophysiologies, create global treatment approaches, and predict prognoses. The manifestations of POTS at all ages are similar , with symptoms of chronic orthostatic intolerance , tachycardia without orthostatic hypotension, and multiple associated disabling symptoms in multiple body systems. In 1 study, 66% of patients reported at least 10 symptoms, 50% of patients reported ≥14 symptoms, and 30% of patients reported ≥26 symptoms.

There has also been a notable female (3.45:1) and white (94.1%) predominance, and association with prior infection or concussion. However, upon closer examination, there are important differences. In children 12 to 19 years of age, the diagnosis of POTS is defined, in part, from tilt table data as an increase in heart rate of ≥40 beats per minute; It is not clear whether this is valid for a 10-minute standing test. Diagnostic criteria also remain undefined in children under 12 years of age.

Diagnostic Criteria for POTS 1. A sustained increase in heart rate of not less than 30 beats per minute within 10 minutes of standing or tilting the head up. For people ages 12 to 19, the required heart rate increase is at least 40 beats per minute. 2. Absence of orthostatic hypotension (i.e., no sustained drop in systolic blood pressure of 20 mmHg or more). 3. Frequent symptoms of orthostatic intolerance during standing, with rapid improvement upon returning to the supine position. Symptoms may include dizziness, palpitations, tremors, general weakness, blurred vision, and fatigue. 4. Duration of symptoms for at least 3 months. 5. Absence of other conditions that explain sinus tachycardia, such as anorexia nervosa, primary anxiety disorders, hyperventilation, anemia, fever, pain, infection, dehydration, hyperthyroidism, pheochromocytoma, use of cardioactive drugs (eg, sympathomimetics, anticholinergics ) or severe impairment caused by prolonged bed rest. |

Risk factors and outcomes

POTS can begin after an infection, concussion, growth spurt, or menarche.

A small percentage of patients have spontaneous resolution of POTS, meaning that most patients remain at least somewhat affected.

Many patients have high academic or sports performance before the onset of the disease.

The presence of parental care, as well as ensuring that patients take responsibility for their own care, are important for the results of symptomatic treatment.

Specific research for pediatric patients with POTS

Findings in Pediatric Patients with POTS

- Post-concussion syndrome is associated with pediatric POTS, and a high percentage of POTS-associated tachycardia resolved as post-concussion symptoms improved.

- The frequency of symptoms in the 10-minute standing test is not significantly different if the increase in heart rate is 30 to 39 or ≥40 beats per minute.

- The prevalence of joint hypermobility is not significantly different if the increase in heart rate is 30 to 39 or ≥40 beats per minute.

- POTS occurs after a growth spurt or menarche.

- Symptoms may decrease after administration of exogenous testosterone .

- Up to 19% of patients with POTS onset during adolescence had resolution of symptoms.

- Up to 48% of pediatric patients were symptom-free at 1-year follow-up and >85% were symptom-free at 6-year follow-up.

- Pediatric patients with POTS have high academic and/or athletic performance.

- Flow-mediated vasodilation is greater than in controls.

- Nitric oxide levels and nitric oxide synthetase activity are elevated compared to controls.

- Hydrogen sulfide levels are higher than in controls.

- Venous pressures at rest are elevated and arterial resistance is decreased compared to controls.

- Total peripheral vascular resistance and cardiac output are reduced in the upright position compared to healthy controls.

- C-natriuretic peptide levels are higher than in controls.

- Resistin levels are elevated compared to controls.

- Supine resistin levels are inversely correlated with the degree of heart rate increase from supine to upright.

- Copeptin levels are elevated compared to controls.

- Antidiuretic hormone levels in patients with hypertension are higher than those without hypertension.

- 24-hour urinary sodium excretion is lower than that of controls.

- Despite peripheral vasoconstriction, upright position induces splanchnic accumulation.

- Baseline orthostatic hypotension occurs more frequently and with greater severity in patients than in controls.

- There is a higher prevalence of alterations in cerebral blood flow and cardiorespiratory regulation in patients compared to controls.

- QTc dispersion is greater in patients than in controls.

- The rate pressure product in patients is greater before and after awakening compared to controls.

- Diurnal variation in heart rate occurs in pediatric POTS.

- New-onset motion sickness , dizziness as a headache trigger, and orthostatic headache are associated with meeting POTS heart rate criteria in patients with new-onset headache and dizziness versus those without do.

- Antroduodenal manometry is often abnormal in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms compared with gastric emptying and endoscopy.

- Anorectal manometry is often abnormal in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms compared with gastric emptying, colonic transit, and gastric accommodation.

- Patients with gastrointestinal symptoms and POTS have bradygastria or tachygastria in the gastric antrum and fundus when standing, while those without POTS have decreased gastric electrical activity.

- In family members of pediatric patients with POTS, 14.2% have POTS, 31.3% have a family member with orthostatic intolerance, 20.2% have a family member with joint hypermobility, and 45.1% have an autoimmune disease.

- Symptomatic therapy for pediatric POTS results in efficacy ranging from 39% to 70%, depending on the symptom.

- Ivabradine improved symptoms in two-thirds of pediatric patients.

- Midodrine and metoprolol reduced symptom scores compared to untreated patients.

- Elevated levels of C-natriuretic peptide and copeptin were predictive of the efficacy of metoprolol treatment.

- β-blockers and, to a lesser extent, midodrine reduced clinical symptoms of POTS.

- Midodrine was effective in the treatment of neuropathic POTS, but not hyperadrenergic POTS.

- Parenteral normal saline reported better quality of life, but those with permanent access were at risk of thrombosis and/or infection.

Symptoms associated with POTS

Taking advantage of problems observed specifically in children and adolescents may help understand the pathophysiology of POTS, as it has not yet been defined. Although a mechanism has been offered for inappropriate peripheral vasoconstriction with compensatory tachycardic response combined with inadequate systemic venous return , it is not clear why this occurs. POTS is noted to occur after growth spurt or menarche and symptoms may decrease after testosterone administration, suggesting a role for sex hormones.

There is concern about the association with immunization, although causality has not been proven and population-based studies have not shown an increase in disease frequency as adolescent vaccination rates increase.

POTS-like findings have been observed in children with mitochondrial disorders. We have anecdotally noted patients with chronic symptoms since infancy or childhood (e.g., dysmotility, headaches, or joint hypermobility) who eventually developed POTS later in childhood, and their parents felt there was always " something wrong" with them. they.

A 2016 study of patients with POTS that began during adolescence demonstrated spontaneous resolution of symptoms in up to 19% of patients by the time they reached adulthood. However, in these patients, POTS symptoms were noted to still be present in up to 33% of respondents who had "recovered" . A similar long-term outcomes study in 2019 from China showed that 48% of pediatric POTS patients were symptom-free at 1-year follow-up, with >85% symptom-free after 6 years, although fewer symptoms were used for diagnosis. evaluation than those of other studies.

Adolescence , when half of POTS patients are diagnosed, is an important time in which many changes occur in the body, demonstrating a significant contrast to adults . During puberty , hormonal changes cause somatic growth, brain maturation, psychological maturation, and gonadal growth and maturation, although it is unclear how they affect onset, pathophysiology, and outcomes. Children attend school and participate in sports, while adults are more sedentary and often have high academic and/or sports performance.

Sleep hygiene can be difficult, especially with the already recognized differences in adolescent sleep. Anecdotally, we have noticed that patients’ symptoms improve when they attend college. This may be due to longer time between classes, with more recovery time, greater neurological maturity allowing for a better ability to recognize and avoid triggers, or being away from parents, forcing them to accept responsibility and manage their illness. Or it could simply be associated with the aforementioned improvement in symptoms over time.

Neurohormonal and hemodynamic alterations

- Patients with POTS show abnormal vascular responses , especially in the upright position.

- There are abnormally high levels of compounds associated with vasodilation.

- In patients, significant venous accumulation of the lower and splanchnic extremities occurs.

Clinical Evaluation

|

Treatment

- There are numerous medications that can be used to reduce the symptoms of POTS.

- Parenteral saline can be used to reduce symptoms as a temporary measure, but is generally not recommended as long-term therapy.

There is a notable paucity of prospective data related to the medication management of pediatric patients with POTS. In fact, the first prospective, double-blind, crossover trial of a medication in POTS in adults, ivabradine , was just published in 2021. Published studies addressing medication utilization in pediatric patients have mostly been retrospective in nature and observational , although they are some small prospective studies.

Although overall therapeutic efficacy for symptoms of lightheadedness, headache, nausea, dysmotility, pain, and insomnia ranged from 39% to 53%, 53 efficacy for fatigue and cognitive dysfunction was higher at nearly 70%.

A meta-analysis was performed evaluating studies using β-blockers in pediatric patients with POTS. The review indicated that these 7 studies demonstrated significant concerns about bias and were not considered to be of sufficient quality. The eighth study, which was judged to be of adequate quality, was a prospective controlled study that was neither blinded nor randomized in evaluating groups receiving routine nonpharmacologic therapy plus a morning dose of 2.5 mg of midodrine, metoprolol twice. daily at 0.5 mg/kg per day, or without medication. Both midodrine and metoprolol therapy reduced symptom scores in children compared to untreated patients, and midodrine led to a higher rate of overall resolution of orthostatic intolerance symptoms.

Lin, who demonstrated elevated levels of C-natriuretic peptide in the study mentioned above, also showed in that same study that metoprolol reduced symptom scores in pediatric patients. Furthermore, a C-natriuretic peptide level greater than 32.55 pg/ml was correlated with the effectiveness of metoprolol in reducing symptoms.

In patients who fail oral medication therapy, parenteral therapy may be an option. The only study in children with this therapy is a retrospective study using intravenous normal saline in patients with POTS, neurally mediated hypotension, or orthostatic intolerance. Most patients reported improved quality of life, although patients who used an indwelling access method, such as a peripherally inserted central catheter or central port, had a notable incidence of vascular thrombosis and infection.

Clinical management

- A complete history that evaluates associated symptoms, as well as comorbid disorders, is key to ensuring a comprehensive therapeutic approach.

- Except for clinical findings associated with comorbidities, physical examination findings may be completely normal.

- Management begins with nonpharmacological interventions, followed by the addition of medications, as indicated.

The general pediatrician’s approach to the care of children and adolescents with POTS, like any clinical concern, begins with evaluation . A complete history is necessary to evaluate the wide range of symptoms associated with POTS, as well as symptoms seen in associated disorders, including, but not limited to, joint hypermobility syndromes, mast cell activation syndrome, craniocervical instability, median arcuate ligament syndrome, and autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren’s syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus.

Physical examination findings may include manifestations of the above disorders, such as an elevated Beighton score, dermatography, urticaria, an epigastric/abdominal murmur, venous pooling, dilated pupils, etc. Often, except for upright tachycardia , the clinical examination may be normal .

Initial studies should include a baseline electrocardiogram, in addition to consideration of 24-hour Holter monitoring to evaluate for arrhythmias. Suggested laboratory investigations include morning cortisol, thyroid function tests, vitamin D level and ferritin because disorders in these can lead to orthostatic intolerance.

Orthostatic intolerance evaluation test Evaluation of orthostatic intolerance includes a 10-minute standing test. Ideally, continuous monitoring of blood pressure and heart rate is performed, but measurements should be obtained at least once per minute . The patient should rest in a supine position for 5 minutes, obtaining heart rate and blood pressure at the end. The patient should then immediately stand for 10 minutes, with minimal stimulation and movement. A persistent increase in heart rate of ≥40 beats per minute without orthostatic hypotension (decrease in blood pressure of 20 mmHg systolic or 10 mmHg diastolic) with symptoms of orthostatic intolerance , plus a history of symptoms for ≥3 months , is diagnostic of POTS (after ruling out other diagnoses), although some sites use a threshold of 30 beats per minute. |

In the absence of finding other treatable etiologies for the symptoms, therapeutic management begins with non-pharmacological intervention , which is essential. The most important initial treatment is to increase intravascular volume with a daily fluid intake of 80 to 120 ounces plus 8 to 10 g of sodium chloride. Other therapies, including elevation of the head of the bed to reduce nocturnal diuresis, adequate sleep hygiene, use of compression garments, and the use of cooling vests to reduce heat intolerance are important complementary measures.

Initiating a specific exercise protocol for POTS patients is important to help suppress symptoms. Fu and Levine developed a protocol that initially used recumbent aerobic exercises , plus isometric activities that strengthened the legs and trunk, which produced a significant and long-lasting reduction in symptoms in adults with POTS. However, the basic principles of exercise for these patients include the following: use both aerobic and isometric exercises, initially avoid upright activities to prevent orthostatic intolerance, start with a minimum duration of exercise, and ensure consistent and progressive exercise. Patients with joint hypermobility are strongly recommended to be evaluated by a physical therapist familiar with hypermobility to teach them how to strengthen and protect their joints.

Often, non-pharmacological therapy for POTS is insufficient to reduce symptoms and patients are unable to resume activities of daily living, let alone incorporate exercise into their routine. Therefore, using medications to reduce POTS symptoms may be beneficial. Although discussion of the utilization of specific medications is beyond the scope of this article, there are basic approaches that can be taken. One is to use medications that target specific symptoms . Another is to take a blanket approach to medication use, aiming to support blood pressure, with the use of therapies such as fludrocortisone or midodrine , while gently lowering the heart rate to improve cardiac output, as with blockade . β or ivabradine .

Many medications used in the management of POTS are already used in children and adolescents for medical disorders, allowing for familiarity. Certainly, these medications can have side effects and patients may have persistent symptoms despite what appears to be adequate therapy. Therefore, comfort in using these medications requires practice, as well as communication with patients and families.

Patients may also require additional referral to specialists, such as cardiologists, neurologists, gastroenterologists, allergists/immunologists, etc., based on specific persistent or abnormal clinical findings, or lack of response to therapy. In the United States, pediatric POTS specialists include general pediatricians, pediatric cardiologists, pediatric gastroenterologists, and child neurologists.