Summary During the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2, some data reports still emerging and in need of comprehensive analysis indicate that certain patient groups are at risk of COVID-19. This includes patients with hypertension, heart disease, diabetes mellitus and clearly the elderly. Many of these patients are treated with blockers of the renin-ngiotensin system . Because the ACE2 protein (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) is the receptor that facilitates the entry of the coronavirus into cells, the idea has become popular that treatment with blockers of the renin-angiotensin system could increase the risk of developing an infection. due to severe and fatal acute coronavirus. This article discusses this concept . ACE2 in its full form is a membrane-bound enzyme, while its shorter (soluble) form circulates in the blood at very low levels. As a monocarboxypeptidase, ACE2 contributes to the degradation of several substrates, including angiotensins I and II. l ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) inhibitors do not inhibit ACE2 because ACE and ACE2 are different enzymes. Although angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers have been shown to upregulate ACE2 in experimental animals, the evidence is not always consistent and differs between various angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers and different organs. Furthermore, there is no data to support the idea that the administration of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers facilitates coronavirus entry by increasing ACE2 expression in animals or humans. Indeed, animal data support elevated ACE2 expression conferring potential pulmonary and cardiovascular protective effects. In summary, based on currently available evidence, treatment with renin-angiotensin system blockers should not be discontinued due to concerns with coronavirus infection. |

The spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) has already assumed pandemic proportions, having infected more than 100,000 people in 100 countries. Although the current primary focus of public health authorities is to develop a coordinated global response to prepare health systems to meet this unprecedented challenge, a concern has been identified that is of particular interest to clinicians and researchers with a strong interest in arterial hypertension.

Hypertension, coronary heart disease and diabetes mellitus, particularly in elderly people, increase susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Since ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) is the receptor that allows the coronavirus to enter cells, the idea emerged that pre-existing use of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers could increase the risk of developing a severe infection. and fatal from SARSCoV-2.

This commentary discusses this concern and concludes that, based on current evidence, there is no reason to abandon RAS blockers in patients receiving this important class of antihypertensive agents due to concerns of increased risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 or worsening its course. .

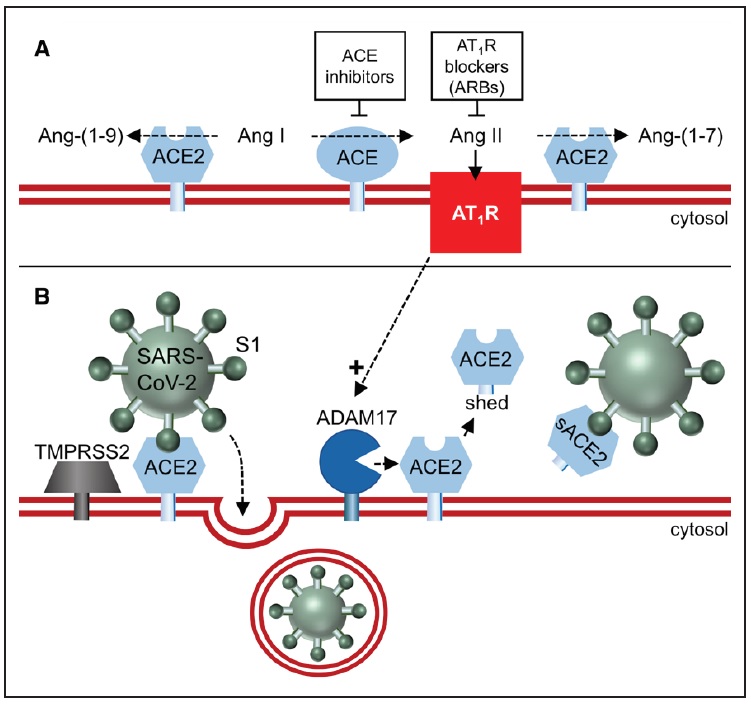

Figure. The carboxypeptidase ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) converts Ang II (angiotensin II) to Ang-(1-7) and Ang I to Ang-(1-9)(A), but is not blocked by ACE (angiotensin conversion enzyme), which prevent the conversion of Ang I to Ang II. ACE2 also binds and internalizes SARSCov-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2; B), after priming with the serine protease TMPRSS2 (transmembrane protease, serine 2). Removal of membrane-bound ACE2 by a disintegrin and metalloprotease 17 (ADAM17) results in the appearance of soluble ACE2(s), which can no longer mediate SARSCov-2 entry and could even prevent such entry by maintaining the virus in solution. AT1R (Ang II, through its type 1 receptor) upregulates ADAM17, and AT1R blockers (ARB) would prevent this.

Figure. The carboxypeptidase ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) converts Ang II (angiotensin II) to Ang-(1-7) and Ang I to Ang-(1-9)(A), but is not blocked by ACE (angiotensin conversion enzyme), which prevent the conversion of Ang I to Ang II. ACE2 also binds and internalizes SARSCov-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2; B), after priming with the serine protease TMPRSS2 (transmembrane protease, serine 2). Removal of membrane-bound ACE2 by a disintegrin and metalloprotease 17 (ADAM17) results in the appearance of soluble ACE2(s), which can no longer mediate SARSCov-2 entry and could even prevent such entry by maintaining the virus in solution. AT1R (Ang II, through its type 1 receptor) upregulates ADAM17, and AT1R blockers (ARB) would prevent this.

Coronavirus and ACE2

In 2003, Li et al4 demonstrated that ACE2 is the receptor responsible for the entry of the SARS coronavirus. Binding to the ACE2 receptor requires the surface unit of a viral spike protein. Subsequent cell entry depends on priming by the serine protease TMPRSS2 (transmembrane protease, serine 2). Two recent reports confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 also enters the cell through this route. Importantly, the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the cell could be blocked by both S protein neutralizing antibodies and TMPRSS2 inhibitors (camostat mesylate).

In the lung, ACE2 expression occurs in type 2 pneumocytes and macrophages. In general, however, pulmonary ACE2 expression is low compared to other organs such as the intestine, testes, heart, and kidneys.

ACE2 shows considerable homology to ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme; 40% identity and 61% similarity) and, on this basis, was named in 2000. As a monocarboxypeptidase, it hydrolyzes multiple peptides, including apelin, opioids, kinins and angiotensins . Much of the work on ACE2 has focused on biological effects related to the formation of angiotensin-(1-7) from angiotensin II.

Unlike ACE, ACE2 does not convert angiotensin I to angiotensin II, nor do ACE inhibitors block its activity.

This is not surprising because homology does not concern the active site. ACE2 is the most potent of the 3 enzymes known to convert the vasoconstrictor angiotensin II to angiotensin-(1-7). Angiotensin-(1-7) increasingly has organ-protective properties that oppose and counteract those of angiotensin II.

The AT1 receptor (angiotensin II, through its type 1) upregulates ADAM17, thereby increasing soluble ACE2 levels. In urine, soluble levels of ACE2 can be significant and probably arise from sloughing of the proximal tubular membrane.

What are the effects of RAS blockers on ACE2?

This is really the crux of the question and the prevailing confusion and panic we are witnessing in the medical community after word spread that ACE2 is the receptor for SARS-CoV-2. Part of the confusion on social media and the general public is because ACE inhibitors are sometimes confused with ACE2 inhibitors. Those are 2 different enzymes with 2 different active sites and any effects of ACE therefore inhibitors of ACE2 activity must be indirect, through their respective substrates. This is unlikely to have any relation to SARS-CoV-2 binding. However, there are limited reports that ACE inhibitors affect ACE2 expression in the heart and kidney.

AT1 receptor blockers (ARBs) alter ACE2 expression most consistently across several studies, both at the mRNA and protein levels. It has been best documented in cardiac tissue and renal vasculature. However, even here, results are mixed, require high doses, and often differ by ARB and organ.

Taken together, there is evidence from animal studies that ARBs can upregulate membrane-bound ACE2, while ACE inhibitors cannot. However, current data are often conflicting and vary between ARBs and tissues (e.g., heart versus kidney). Even if the reported upregulation of tissue ACE2 by ARBs in animal studies and generally at high doses could be extrapolated to humans, this would not establish that it is sufficient to facilitate entry of SARS-CoV-2.

We would like to point out that a potentially beneficial pulmonary effect of ARBs should also be considered . During acute lung injury, alveolar ACE2 appears to be downregulated. This would decrease the metabolism of angiotensin II, resulting in increased local levels of this peptide, increasing alveolar permeability and promoting lung injury. In this context, it can be speculated that having increased ACE2 expression by pre-existing ARB treatment may actually be protective in the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Risks of abandoning ACEI/ARB treatment in patients with coronavirus

| It is unclear how hypertension was coded in the recent SARSCoV-21 report: we can only speculate that it could be based on the use of hypertension medications rather than actual blood pressure measurement. |

To truly address whether patients with hypertension are more likely to develop severe and fatal SARSCoV-2 infections, a prospective cohort study with incidence rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a cohort of patients with hypertension and patients is required. without hypertension , with similar exposure history. Instead, what has been reported is a history of hypertension versus no , in patients with SARS-CoV-2, without any adjustment (e.g., for age).

The use of RAS blockers as a causal link is an assumption that lacks evidence , as discussed here. Therefore, we strongly recommend that patients taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs for high blood pressure, heart failure, or other medical indications should not withdraw their current treatment regimens unless specifically recommended by their doctor or healthcare provider. . There is an additional warning. Any resulting destabilization of blood pressure control in hypertension, which could occur with changes in medication, would carry unacceptable risks of strokes and precipitated heart attacks, risks that are clearly not just hypothetical. Simply discontinuing antihypertensive agents is discouraged and should not be an option, considering the widespread use of RAS blockers worldwide. In particular, Asian people appear to be more prone to cough and therefore ARBs may be preferable. |

Next steps

The clinical database available from the pandemic to date is insufficient to provide sufficient details on the variables of interest: diagnosis of hypertension and prescribed antihypertensive medications to test the proposed hypotheses and provide certainty. Therefore, such information is desperately needed.

Although no therapy has currently been established for patients with SARSCoV-2, the field is moving rapidly with potential approaches under consideration. These include broad-spectrum antivirals such as favipiravir and remdesivir, inhibition of TMPRSS2 with camostat mesylate, and upregulation of ADAM17.

A more targeted approach could be to use the soluble recombinant ACE2 protein to prevent the virus from binding to the full-length ACE2 anchored in the cell plasma membrane. These approaches make the most sense for the treatment of patients at high risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome. For preventive purposes, the goal, of course, is the development of a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2.

In conclusion, we see no reason to abandon or temporarily suspend the use of RAS blockers preventively in patients with SARSCoV-2.

There are some concerns that these agents, particularly ARBs, may affect ACE2 expression based on animal models that, however, have not been challenged with coronavirus infection to evaluate the impact of RAS blocking therapy. Since this information is missing, we see no reason to panic and alter the prescribing of this critically important class of antihypertensives.

Its therapeutic benefit, in our opinion, outweighs any potential risk of predisposition to coronavirus infection. Furthermore, it is unknown whether alternative antihypertensive drugs do not carry the same risk.

Another question is what to do in infected individuals at risk of progressing to end-stage renal disease. The decision here should be based on clinical judgment and consider the pros and cons of RAS blockade in acutely ill patients, such as the presence or absence of hypotension and the possible effect on renal function.

Messages for practice

|