Data and numbers

|

Human echinococcosis is a zoonosis (that is, a disease transmitted to humans by animals) caused by parasitic tapeworms of the genus Echinococcus that occurs in four forms:

- cystic echinococcosis or hydatidosis, which is a product of infestation by Echinococcus granulosus ;

- alveolar echinococcosis, caused by infestation by E. multilocularis ;

- two forms of neotropical echinococcosis: polycystic, caused by infestation by E.

vogeli ; and - unicystic echinococcosis, due to E. oligarthrus .

The two most important forms, which have medical and public health significance for humans, are the cystic and the alveolar.

Transmission

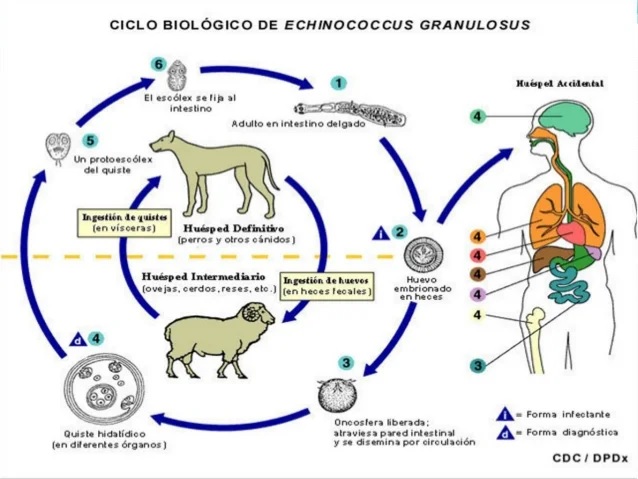

Several herbivorous and omnivorous animals are intermediate hosts of Echinococcus that become infected by ingesting parasite eggs present in contaminated food and water; Subsequently, the parasite evolves in the viscera of the animal to the larval stages.

The definitive hosts are carnivorous animals that harbor the mature tapeworms in their intestines. These animals become infested by consuming viscera of intermediate hosts that contain parasite larvae.

Humans accidentally act as intermediate hosts because they become infested in the same way as other intermediate hosts but do not transmit the parasite to definitive hosts.

Several genotypes of E. granulosus are known to have different preferences for different intermediate hosts, and some genotypes are considered distinct species of E. granulosus . Not all genotypes infect humans. The genotype causing the vast majority of human cases of hydatidosis mainly follows a dog-sheep-dog cycle, although other domestic animals such as goats, pigs, cows, camels or yaks may also participate in it.

The life cycle of E. multilocularis , which causes alveolar echinococcosis, is usually wild and includes foxes and other carnivores and small mammals (especially rodents) as intermediate hosts, while domestic dogs and cats can also be definitive hosts.

Signs and symptoms

Hydatidosis

Upon ingestion, E. granulosus produces one or more hydatid cysts, often located in the liver and lungs, and less frequently in the bones, kidneys, spleen, muscles, central nervous system, and eyes.

The asymptomatic incubation period can last many years, until the hydatid cysts reach a size that causes clinical signs. However, about half of patients taking drug treatment are prescribed it in the first few years after infection.

The hepatic location of hydatids usually causes abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. When they affect the lungs, the clinical signs are chronic cough, chest pain and dyspnea. Other signs may also appear depending on the location of the hydatid cysts and the pressure they exert on the surrounding tissues. Some nonspecific signs are anorexia, weight loss, and weakness.

Alveolar echinococcosis

Alveolar echinococcosis is characterized by an asymptomatic incubation period of 5 to 15 years and the slow development of a primary tumor-like lesion, usually in the liver. Clinical signs are weight loss, abdominal pain, malaise, and signs of liver failure.

Larval metastases can spread both to organs adjacent to the liver (for example, the spleen) and to distant sites (such as the lungs or brain) when the parasite travels through the blood and lymphatic circulation. If left untreated, alveolar echinococcosis is progressive and fatal.

Distribution

Hydatidosis is distributed throughout the world and is found on all continents except Antarctica, while alveolar echinococcosis is limited to the northern hemisphere, in particular, to some areas of China, the Russian Federation and countries in continental Europe and from North America.

In endemic regions, human hydatidosis incidence rates can be more than 50 per 100,000 person-years, and prevalence can reach 5%-10% in some areas of Argentina, Peru, Africa Eastern, Central Asia and China. In livestock animals, the prevalence of hydatid disease observed in slaughterhouses in hyperendemic areas of South America varies between 20% and 95% of slaughtered animals.

The highest prevalences are found in rural areas, where older animals are slaughtered. Depending on the infected species, livestock production suffers losses attributable to hydatid disease resulting from the declaration of the liver as unfit for consumption, and may also result in lower carcass weight, a loss of skin value, decreased milk production and reduced fertility.

Diagnosis

Ultrasound is the technique of choice to diagnose hydatid disease and alveolar echinococcosis in humans and is usually complemented or validated by computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging.

Cysts may be discovered incidentally on an x-ray.

There are different serological tests that detect specific antibodies and can help in the diagnosis. Early detection of E. granulosus or E. multilocularis infestation , especially in resource-poor settings, remains necessary to select between different clinical treatment options.

Treatment

Treatment of echinococcosis, both the cystic and alveolar forms, is often expensive and complicated, sometimes requiring major surgery and/or prolonged drug therapy. There are four therapeutic options for hydatid disease:

- percutaneous drainage of hydatid cysts with the technique called PAIR (puncture, aspiration, injection and reaspiration);

- surgical intervention;

- treatment with anti-infective drugs;

- and the expectant attitude.

The choice should be based mainly on the ultrasound images of the cyst and depends on the specific phase in which it is found, the health infrastructure and the human resources available.

In alveolar echinococcosis, early diagnosis and radical surgery (similar to that applied with tumors) continue to be essential, followed by anti-infective prophylaxis with albendazole. If the lesion is limited, radical surgery can be curative, but unfortunately, the disease is often diagnosed at an advanced stage and, if palliative surgery is not complemented by complete and effective anti-infective treatment, frequent complications occur. relapses.

Burden on health and the economy

Both hydatid disease and alveolar echinococcosis cause significant morbidity and mortality. More than one million people worldwide may suffer from these diseases at any given time, many of whom will develop severe clinical syndromes that, if left untreated, can be fatal. Likewise, there are many cases of treated patients who lose quality of life.

The average mortality after surgical intervention to treat hydatid disease is 2.2% and in about 6.5% of cases recurrences appear that delay recovery.

The WHO Reference Group on the Epidemiology of Foodborne Disease Burden estimated in 2015 that echinococcosis causes 19,300 deaths and the loss of 871,000 disability-adjusted life years each year (1 ) .

The total annual costs of hydatidosis treatment and losses to the livestock industry are estimated to be US$3 billion.

Surveillance, prevention and control

Reliable surveillance data are essential to determine the burden of the disease and evaluate the progress and success of control programs. However, as with other neglected diseases that primarily affect disadvantaged populations and remote areas, data are scarce. Therefore, it will be necessary to pay more attention to this issue to implement control programs and measure their effects.

Hydatidosis

Surveillance for hydatid disease in animals is difficult because the infestation is asymptomatic in cattle and dogs. Furthermore, communities and local veterinary services do not recognize or prioritize the importance of surveillance.

Hydatidosis can be prevented, since the intermediate and definitive hosts are domestic animals. Regular deworming of dogs with praziquantel (at least four times a year), improving hygiene in slaughterhouses (including properly destroying infected offal) and public education campaigns have been proven to reduce transmission (and prevent in high-income countries), in addition to alleviating the burden of human morbidity and mortality.

Vaccination of sheep with a recombinant E. granulosus antigen (EG95) offers encouraging prospects for prevention and control. Currently, this vaccine is authorized and marketed in China and Argentina. In the latter country, trials have demonstrated the advantages of vaccinating sheep, while in China the vaccine is widely administered.

A program combining vaccination of sheep, deworming of dogs and culling of older sheep could lead to the elimination of human hydatid disease in less than 10 years.

Alveolar echinococcosis

The prevention and control of alveolar echinococcosis is more complex, since wild animals intervene in its cycle as intermediate and definitive hosts. Periodic deworming of domestic carnivores that may come into contact with wild rodents should help reduce the risk of human infestation.

In studies conducted in Europe and Japan, deworming by anthelmintic baiting of wild and stray animals that may be definitive hosts has produced significant reductions in the prevalence of alveolar echinococcosis. On the other hand, culling foxes and stray dogs without owners has been proven to be ineffective and it is debatable whether it is sustainable or profitable.