Eosinophils are multifunctional leukocytes, normal constituents of the gastrointestinal tract, except when present in the squamous epithelium of the esophagus.

Homeostatic eosinophils reside primarily in the lamina propria of the small intestine and protect against parasites and pathogenic bacteria. These cells are selective in their response to parasites, allowing some to reside in the mucosa, thus regulating the intestinal microbiome and participating in tissue homeostasis.

Eosinophils also modulate the immune response, through the secretion of cytokines that can activate dendritic cells and induce IgA class switching in B cells. In their homeostatic role, eosinophils are distributed evenly and sparsely within the lamina propria and do not form clusters or undergo degranulation.

In the small intestine, eosinophils maintain IgA concentrations through secretory factors that prolong the survival of IgA-secreting plasma cells and induce the production of secretory IgA.

This immunoglobulin is an important first-line defense in the mucosa, preventing the invasion of pathogenic microorganisms by covering them with a hydrophilic envelope that is repelled by the mucosal epithelium, thus allowing expulsion.

Both tissue and peripheral eosinophilia have long been known as evidence of parasite invasion, and as every pathologist knows, when eosinophils predominate in the gastrointestinal mucosa, it is good to keep in mind the principle of "see eosinophils, think parasites ."

Its excessive presence is not beneficial, as in asthma and eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders, in which the recruitment of eosinophils is induced by pathogens or allergens, causing epithelial damage.

In asthma, the phenotypes of the different diseases are clear, and the manifestation of the disease does not depend only on a direct relationship with the number of eosinophils, but also on the interaction between genetic predisposition and the microbiome.

This interaction is less known in eosinophilic disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, with the exception of eosinophilic esophagitis, characterized by eosinophilia in the squamous mucosa, in which a similar interaction between genetics, the microbiome and allergens has been proven ( particularly food).

Primary eosinophilic disorders include eosinophilic esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and colitis. Gastrointestinal involvement can also be seen in hypereosinophilic syndrome.

Secondary causes of gastrointestinal eosinophilia are numerous, including food hypersensitivity, drug reactions, parasitic infestation, and malignant tumors, being more common than primary eosinophilic diseases.

Other gastrointestinal diseases are also characterized by increased numbers of eosinophils, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease and inflammatory bowel disease.

Classification of gastrointestinal disorders associated with eosinophils Primary eosinophilic diseases. • Eosinophilic esophagitis Secondary eosinophilic infiltration in disease . • Infection: e.g. For example, parasitic or Helicobacter pylori Gastrointestinal diseases associated with increased eosinophils • Functional dyspepsia. |

This review focuses on the less studied eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders, such as gastroenteritis and colitis, as well as the more recently described, duodenal eosinophilia, linked to functional dyspepsia, and focal eosinophilic colitis linked to colonic spirochetosis.

All of these eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders are characterized by an excess of eosinophils in the mucosa, submucosa, or muscularis of the stomach, small intestine, or colon; often its cause is unknown. Hypereosinophilic syndrome with gastrointestinal involvement is also briefly described.

| Eosinophilic gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis |

> Epidemiology

Review of a US population-based database of more than 35 million children and adults reported an overall prevalence of eosinophilic gastroenteritis of 5.1/100,000 and eosinophilic colitis of 2.1/100,000 people. However, in other studies the prevalence was almost double. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is somewhat more prevalent in children, while eosinophilic colitis is more prevalent in adults.

These disorders prevail in the third and fourth decades of life. In the US, higher prevalence was found in northern states, and in urban and suburban areas more than in rural areas. The prevalence is also slightly higher in women and white individuals, and most patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis have a relatively high level of education.

It is noteworthy that eosinophilic gastroenteritis and colitis are associated with allergic diseases, and patients often have concurrent drug allergies, rhinitis, asthma, sinusitis, dermatitis, food allergies, eczema, or urticaria.

It has been proven that there are cases of autoimmune connective tissue diseases in patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. There are reports of 19 published cases that show an association between the two.

| In 35% of these patients, an association was found with systemic lupus erythematosus, 20% with rheumatoid arthritis, 15% with systemic sclerosis, and 15% with inflammatory myositis. |

> Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of eosinophilia present in eosinophilic gastroenteritis and colitis is poorly studied. Histopathology is characterized by an excessive number of eosinophils with signs of degranulation.

It is known that in eosinophilic esophagitis, food allergens drive eosinophil infiltration, since their elimination from the diet is an effective therapy; 74% of individuals with a diet in which 6 foods were eliminated showed an improvement in symptoms and histological resolution.

The association of allergy and atopy in eosinophilic gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis suggests that in some people other allergens could also be responsible, since half of the patients with eosinophilic gastritis showed positivity to skin sensitivity tests for food allergens or aeroallergens. , with an increase in the count of eosinophils in the blood.

A gastric transcriptome, including T-helper-type immunity driven by interleukins 4, 5 and 13, was observed in patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis and increased expression of genes involved in potential operative pathways.

The authors maintain that it is important to highlight that this transcriptome had more than 90% correlation with eosinophilic esophagitis, suggesting that similar treatments could be effective for both conditions.

However, some patients with eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders have a shared autoimmune component without atopy, which could lead to eosinophilia through different immunological pathways, indicating the complexity of this disease.

Gastrointestinal dysbiosis could also play a role in the pathophysiology of these disorders. Alterations in the gut microbiota have been implicated in allergy, but it is unknown whether this is a cause or consequence of the disease.

The combination of genetic predisposition, dysbiosis, and environment (e.g., ingested or inhaled allergens) likely sets the stage for eosinophilia in eosinophilic colitis and gastroenteritis, but more research is needed to determine the underlying pathogenesis of these disorders. complex.

| Clinical presentation |

Patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis usually present with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms, with a blood eosinophil count that may be normal.

Some studies report that the majority of patients (80%) have at least mild peripheral eosinophilia.

Gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis are often associated with esophageal symptoms of reflux disease, dysphagia, and other vague symptoms including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, failure to thrive, diarrhea, and weight loss. More serious conditions have also been observed: ascites, volvulus, intussusception, perforation and obstruction.

The clinical presentation probably depends on the site and extent and depth of the disease in the gastrointestinal tract. Patients with more extensive eosinophilic involvement, beyond the mucosa, in the muscularis, may present obstruction while those with serosa involvement could present ascites.

Although esophageal eosinophilia and diagnosed eosinophilic esophagitis have been observed in children with eosinophilic gastroenteritis, there is only one case report in adults. Among 30 children with eosinophilic gastritis, 28 underwent simultaneous esophageal biopsies. Twelve (43%) had concurrent eosinophilic esophagitis (≥15 eosinophils/high-power field). No patient had concurrent eosinophilic colitis, although only 7 (23%) underwent colon biopsies.

| Diagnosis |

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis may be suspected on endoscopic study, and imaging may be useful in judging the extent of the disease, but a biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis.

Endoscopy, imaging and histopathology.

In patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis, endoscopic findings may appear normal or may present: erythema, white spots, focal erosions, ulcerations, fold thickening, polyps, nodules, and friability.

In 15 patients, endoscopic findings were largely nonspecific: most had erythema, but 2 patients had ulcers in the duodenal antrum.

In eosinophilic colitis, colonoscopy may reveal patches of mucosal edema, punctate erythema, raised whitish lesions, pale granular mucosa, and aphthous ulceration, although these findings are rare and unreliable.

Regarding images, mucosal involvement in eosinophilic gastroenteritis can be evidenced by the presence of thickening of the folds, polyps and ulcers on computed tomography (CT).

In the disease with involvement of the muscular layer, reduced distensibility, stenosis and thickening of the folds can be observed. If the serosa is affected, there may be ascites, omental thickening and lymphadenopathy.

Images of eosinophilic colitis in adults and children have only been described in case reports and small series. The characteristics in these patients are the presence of the “spider leg” sign generated by diffuse thickening of the mucosa; This sign occurs when the contrast markedly penetrates the mucosal sinuses, in the longitudinal section of the intestine on the CT. When there is mucosal involvement, concentric thickening of the colon and ascites has been observed.

In the largest series of children with eosinophilic colitis and radiological findings published to date, an abnormal colon was noted in 6 of 7 patients, with parietal, austral (in isolation), and circumferential thickening.

Histology of gastrointestinal mucosal biopsies is the gold standard for the diagnosis of eosinophilic gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis, and the main diagnostic criterion is excess mucosal eosinophilia in the absence of a known cause.

However, the number of eosinophils needed to make a diagnosis is not as well defined as in eosinophilic esophagitis (15 eosinophils/high power field).

In a recent review, 30 eosinophils/high-power field was a number considered reasonable to make the diagnosis of eosinophilic gastritis, while >50 eosinophils/high-power field in the right colon has been suggested for the diagnosis of eosinophilic colitis, > 35 eosinophils/high-power field in the transverse colon or, 25/high-power field in the left colon. (table).

For diagnosis, higher counts have also been proposed, along with other histological characteristics, but they are only suggestions derived from case series and so far they have not been validated in different populations, as is the case of eosinophilic esophagitis. There are currently no formal guidelines for the diagnosis of mucosal biopsy.

It should be kept in mind that eosinophils are normal constituents of the intestine and that numbers can vary widely among individuals, depending on region, climate, age, exposure to food allergens and infectious agents.

When evaluating biopsy samples, these factors must be considered. These factors can raise doubts about the diagnosis, meaning that there are cases that could go unnoticed unless eosinophils are routinely counted in all biopsies.

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis was originally classified in 1970 according to the site of infiltration of eosinophils: mucosal, muscular, or serous.

A study of 40 patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis carried out in 1990 showed that 23 of them had mucosal disease, 12 had the muscular layer affected, and 5 the subserosa layer. A subsequent examination clearly indicated that a shift from muscularis to mucosal involvement had occurred.

In this study, 52 patients had mucosal disease, 3 had muscular layer disease, and 4 had subserous disease. Although this change could be an endoscopic diagnostic criterion, it is likely that cases can now be diagnosed earlier than the original series, by performing a biopsy of the superficial mucosa instead of the traditional full thickness biopsy, with the consequent reduction in progression. from the muscular to the serosa layer, secondary to effective treatment, compared with previous reports.

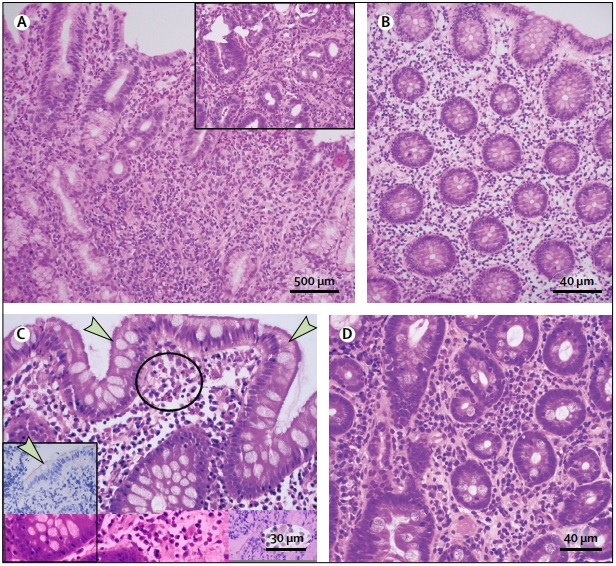

The histopathology of the mucosa in original gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis is similar and is described as excess eosinophils in the lamina propria, with degranulation and possible infiltration of the superficial epithelium and crypts, with formation of superficial and crypt abscesses.

The epithelium could show degenerative and regenerative changes, with foveolar and crypt hyperplasia. Often, a considerable excess of eosinophils arranged in sheets or groups is observed.

(A) Eosinophilic gastritis with sheets of >30 eosinophils per high-power field (HPF) in the lamina propria, grouped around glands (inset). (B) Eosinophilic colitis, biopsy from the left colon, with > 35 eosinophils per HPF in the lamina propria. (C) Colonic spirochetosis, a blue haze on hematoxylin and eosin staining adhered to the surface of the colonic epithelium (indicated by arrows), with clusters of eosinophils in the lamina propria (circle); the inset shows immunohistochemistry to identify surface spirochetes (indicated by the arrow). (D) Duodenal eosinophilia in a patient with postprandial distress type functional dyspepsia with 36 eosinophils per 5 HPF in the lamina propria

Large deposition of extracellular eosinophil granule major basic protein, detected by immunohistochemistry, is indicative of eosinophil degranulation and has been observed more frequently in patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis than in healthy controls.

Degranulation can mask eosinophil counts, as occurs in eosinophilic esophagitis, in which the number of eosinophils found in the squamous epithelium was significantly higher when using major basic protein immunostaining than with hematoxylin-eosin .

> Biopsy sites for eosinophilic gastroenteritis

The choice of intestinal endoscopic biopsy sites is important when the diagnosis is uncertain, particularly that of eosinophilic gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis. The pathology may be irregular, and therefore, in order to confirm the diagnosis, it is advisable to take biopsy samples from all regions of the intestine, including obvious macroscopic lesions.

Good practice is to rely on the Sydney system for recommended biopsy sites of the gastric body, antrum, and incisura; The authors recommend that at least 4 biopsy samples be taken from the first and second portion of the duodenum, as applied for the diagnosis of celiac disease in patchy disease, placing the samples in separate containers.

If eosinophilic gastroenteritis is suspected in pediatric patients, it is also recommended to perform biopsies of the esophagus, gastric body, antral mucosa, and duodenum.

For the diagnosis of eosinophilic colitis not associated with macroscopically visible lesions, the same criteria can be applied as for inflammatory bowel disease, both in adults and children, with optimal performance when samples are taken from multiple sites, providing greater precision. diagnosis and better interobserver diagnostic agreement.

Therefore, in these cases, the authors recommend obtaining random biopsy samples from the terminal ileum and each colonic segment of the colon (from the cecum to the rectum), placing the samples in separate containers.

> Differential diagnoses

Although it has been shown that eosinophilic gastroenteritis and colitis are associated with other diseases, particularly allergy , the exact pathogenesis is unknown.

Therefore, these diseases are diagnosed by exclusion, since an excessive number of eosinophils in the intestine can be seen in many conditions that require clinicopathological investigation. If eosinophilia is present, an infection should be suspected.

The most well-known infections that induce eosinophilia are parasitic ones. Travel history and parasitological examination of stool for eggs and parasites is good practice if the biopsy shows eosinophilia. Recent reports of patients with colonic spirochetosis associated with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation have shown characteristic eosinophilia on colonic biopsy, with adjacent clusters of spirochetes in the superficial colonic epithelium.

It has been found that in the general population undergoing colonoscopy, 2.3% had eosinophilic colonic spirochetosis . Counts were higher in patients with colonic spirochetosis than in those without spirochetosis, even in the rectum.

Individuals with colonic spirochetosis are more likely to have inflammatory bowel syndrome than those without it. Diarrhea occurred in 62% of patients, compared to 31% of controls, and abdominal pain in 52%, compared to 17% of controls.

Gastric eosinophilia may be associated with Helicobacter pylori infection , both before and after eradication treatment. Drug hypersensitivity can also trigger eosinophilia; for example, mycophenolate and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. However, because these are commonly used, they should always be considered within the differential diagnosis.

In food hypersensitivity as in allergic proctocolitis there is a varied prevalence in all healthy babies with an adverse reaction to cow’s milk protein, ranging from 0.3% to 7.5%. In a prospective study, 14 of 22 infants (64%) with rectal bleeding had allergic colitis (defined by the number or location of eosinophils), 5 (23%) had normal biopsies, and 3 (13%) had nonspecific colitis.

Rectal bleeding in all infants with normal biopsies or nonspecific colitis resolved without dietary modification, except for one infant, who was subsequently diagnosed with childhood inflammatory bowel disease.

Biopsies of rectal mucosa in allergic proctocolitis are characterized by an increase in the number of eosinophils in the lamina propria, the superficial epithelium and the crypts, and the muscularis mucosa, without significant architectural changes.

Typically, this diagnosis is clinical and symptoms resolve 2 to 3 days after removal of the cow’s milk protein. Colon biopsies from patients with food allergies (a wide range of foods) show increased colonic eosinophils, with degranulation.

An increase in duodenal eosinophils has been described in active celiac disease. More recently, prominent infiltration of eosinophils (up to 50 eosinophils/high-power field) has been demonstrated in 150 patients with celiac disease. It was suggested that eosinophils are involved in mucosal damage since they were found in the most advanced histological stages.

Gastrointestinal biopsies in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases show eosinophils in variable numbers. When eosinophils are found in gastric biopsies, an inflammatory bowel disease should be suspected, since colon biopsies in patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis also show a greater number of eosinophils in the lamina propria, compared to controls.

Eosinophilic infiltration of the gastrointestinal tract has also been observed in connective tissue disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, vasculitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

| Functional dyspepsia and duodenal eosinophilia |

Eosinophilia has been described in duodenal biopsies from patients with functional dyspepsia, particularly in those with early satiety, although the number of eosinophils is lower than that observed in eosinophilic gastroenteritis.

In a Swedish study, functional dyspepsia in individuals with elevated eosinophil counts in D1 (duodenal bulb) (>22 eosinophils/5 high-power fields) had an odds ratio of 11.7.

Eosinophilia on D1 was significantly associated with early satiety, implicating duodenal eosinophilia in the onset of postprandial distress, a subtype of functional dyspepsia, with 52 eosinophils/5 high-power fields compared to 34 eosinophils/5 high-power fields in the controls. Disrupted intestinal barrier and impaired neuronal function have been shown to accompany duodenal eosinophilia in ex vivo biopsies from patients with functional dyspepsia.

In ex vivo biopsies of patients with functional dyspepsia, an increase in duodenal permeability (measured by transepithelial electrical resistance) and paracellular permeability was also found throughout the duodenum with eosinophilia and mast cell infiltration.

In these patients, neuronal signaling, as measured by calcium responses to electrical and chemical depolarization, was altered in the submucosal plexus, with a significant negative correlation between the calcium response to electrical stimulation and the number of eosinophils.

It is possible that these observations reflect an organic mechanism of the disorder in patients with functional dyspepsia, by which an allergen or infection causes the interruption of the barrier and the generation of a T-helper 2 type immune response, which induces the recruitment and eosinophil degranulation, which in turn affects the submucosal nervous system and gastroduodenal function. Peripheral eosinophilia has not been observed in functional dyspepsia.

| Hypereosinophilic syndrome with gastrointestinal involvement |

Currently, hypereosinophilic syndrome is defined by an absolute blood eosinophil count >1,500 cells/μl, for more than 1 month (although if severe end-organ damage is occurring, the diagnosis can be made immediately, to avoid therapeutic delays). .

Tissue hypereosinophilia with evidence of eosinophil-mediated target organ damage may also be observed, but all known causes of hypereosinophilia must be excluded before making the diagnosis of hypereosinophilic syndrome.

Secondary causes of blood eosinophilia include: parasitic or viral infections, allergic diseases, medications and chemicals, hypoadrenalism, and cancer. Hypereosinophilic syndrome is characterized by multiorgan infiltration of eosinophils as opposed to single organ involvement as occurs in eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders.

It has been proposed that if eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders coexist with blood hypereosinophilia and only one organ is affected, the term hypereosinophilic overlap syndrome may be used . Organ involvement in this syndrome may include chronic Budd-Chiari syndrome, active hepatitis, eosinophilic cholangitis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and eosinophilic colitis, but not eosinophilic esophagitis.

Of note, the systemic mast cell disorder, systemic mastocytosis, can also manifest with intestinal eosinophilia, stimulated by the localized release of eosinophilic chemotactic mediators.

| Treatment of eosinophilic gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis |

Secondary causes, such as medications or parasitic infections, must be carefully evaluated and treated. If there is a micronutrient deficiency, it must also be corrected. Colonic spirochetosis, which is associated with colonic eosinophilia and gastrointestinal symptoms, can be treated with metronidazole .

This treatment has been shown to improve gastrointestinal symptoms, although randomized trials are lacking. Also, therapies that have some efficacy in the treatment of functional dyspepsia with duodenal eosinophilia include leukotriene receptor antagonists montelukast and proton pump inhibitors (possibly due to botain inhibition).

However, it has not been demonstrated that these or other therapies produce an improvement in the symptoms of functional dyspepsia as a result of the stabilization or reduction of the number of eosinophils.

If no secondary cause of eosinophilia is found, the diagnosis of eosinophilic gastroenteritis or eosinophilic colitis can be made, with several therapeutic options, although the evidence for most therapies is limited to case reports and small uncontrolled case series.

| Diet therapy |

Dietary therapy is recommended as first-line treatment for eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders.

Empirical food elimination diets, which exclude commonly implicated dietary antigens (milk, wheat, soy, eggs, nuts, and shellfish), have been shown to be effective in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis, indicating that food is an important antigenic trigger in prototypical eosinophilic disease.

Various food elimination diets appear to be effective in eosinophilic gastroenteritis; However, the evidence is limited to case reports and small casuistries. In these, one of the largest studies, a retrospective case series of 17 children with eosinophilic gastroenteritis, showed a clinical response rate to that diet of 82%.

Although some case reports describe successful results from elimination of specific foods based on allergy testing, treatment response has been reported to fail in food allergies identified by skin sensitivity testing or measurement of serum IgE concentrations. specific to foods, suggesting that selective elimination of foods may not be effective.

In fact, specific food allergy testing is not currently recommended for the treatment of eosinophilic gastroenteritis.

75% of infants fed a rigorous exclusionary elemental diet also showed the effectiveness of that diet for the treatment of eosinophilic gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis; however, compliance among older children and adults is likely to severely limit its usefulness.

| Corticosteroids |

Corticosteroids are used as first-line pharmacological treatment for eosinophilic gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis, when dietary therapy has not achieved an adequate clinical response. Oral prednisone 20–40 mg/day for 2 weeks has been shown to induce clinical remission in most patients, although some reports recommend higher doses (0.5–1 mg/kg).

Patients whose symptoms relapse during or after tapering of the drug may require continued maintenance treatment. Systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone are often used in low doses (5-10 mg/day, or the minimum dose required to maintain response).

However, due to the undesirable long-term side effects of systemic corticosteroid therapy, other alternative agents less likely to reach the systemic circulation may be considered. A good response has been achieved with the use of budesonide (3-9 mg/day); Oral fluticasone has been shown to decrease concurrent gastric eosinophilia in children with eosinophilic esophagitis.

| Steroid sparing agents |

In individuals who require maintenance therapy with corticosteroids or who do not respond adequately to their action, several agents have been used, with positive results. Several of these agents are those used for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, such as mesalazine (or 5-aminosalicylic acid), azathioprine, and anti-TNF agents, such as infliximab and adalimumab.

Other options include mast cell stabilizers, such as sodiumcromoglycate and ketotifen, and the leukotriene receptor antagonist montelukast, omalizumab, an anti-IgE agent, which has been shown to significantly improve symptoms and lower the count. of gastroduodenal eosinophils in 9 individuals with eosinophilic gastroenteritis.

It was found that the interleukin 5 blocking agent mepolizumab induced a response in a group of 6 patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis or hypereosinophilic syndrome; However, rebound eosinophilia was observed in all responders, with associated clinical relapse.

A new antibody directed against CCR3, an eotaxin receptor expressed by eosinophils, which facilitates their recruitment to sites of inflammation, has been shown to decrease eosinophilic inflammation and diarrhea in a mouse model of eosinophilic gastroenteritis.

| Fecal microbiota transplant |

Fecal microbiota transplantation has been shown to be effective for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases, including refractory Clostridium difficile infection and ulcerative colitis.

This treatment has been used successfully in a patient with eosinophilic enterocolitis involving the ileum and colon, whose disease was refractory to enteral nutrition, azathioprine, steroids, and surgical resection, but responded to fecal microbiota transplantation from a single donor. , in addition to oral corticosteroids.

| Surgery |

Patients may present complications of intestinal inflammation including stricture or perforation, and require surgical therapy; They can be diagnosed incidentally in a surgically resected specimen.

However, even in the setting of an acute abdomen, known (or highly suspected) eosinophilic gastroenteritis, or eosinophilic colitis, symptoms may respond to conservative management with immunosuppressants.

| Hypereosinophilic syndrome with gastrointestinal involvement |

Treatment for hypereosinophilic syndrome is different from treatment for eosinophilic gastroenteritis and colitis. Corticosteroids, tyrosine kinase inhibitor agents, such as imatinib, hydroxyurea, interferon-α, and anti-interleukin 5,1 are effective for the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndrome. The antiparasitic agent ivermectin is recommended for Strongyloides infection .

| Clinical course of eosinophilic gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis |

The clinical course of these conditions has been described based on a follow-up of 43 patients, of whom the majority had spontaneous remission or responded to first-line therapy. Over a median follow-up of 13 years, 42% of these patients did not suffer relapses, 37% exhibited a course of relapses and remissions, and the remaining 21% had chronic disease without remission.

Follow-up for more than 1 year of study patients with eosinophilic colitis showed that 5 (45%) had relapses after stopping steroids (13 episodes); 2 of them required long-term maintenance treatment with prednisone; 1 patient required ileal resection due to perforation.

Although there were only 2 small studies, the data suggest that patients who respond to initial diet or corticosteroids should be monitored long term. In patients who relapse during reduction or cessation of corticosteroid therapy, corticosteroid therapy may be increased or restarted, with a view to transitioning to a corticosteroid with lower bioavailability or a steroid-sparing agent.

| Conclusions and future directions. |

Currently, eosinophilia throughout the intestinal tract can be recognized as a primary eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder (eosinophilic gastroenteritis or eosinophilic colitis), or secondary to a cause known as parasitic infection.

New eosinophilic intestinal diseases have also been recognized, such as duodenal eosinophilia in functional dyspepsia and colonic spirochetosis, with a greater number of colonic eosinophils.

Therefore, a thoughtful clinicopathological approach is needed to ensure that a correct diagnosis and targeted treatment are made. More case-control and cohort studies are required to better characterize the etiological factors and natural history of the disease.

Rigorous therapeutic studies examining steroid-sparing agents are also needed to provide safe and effective therapy for patients requiring long-term maintenance treatment.

It is hoped that as research progresses, the cause (or causes) of primary eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders can be determined, allowing the successful targeting of first-line therapies for these disorders, rather than a trial and error approach. which constitutes current practice.