The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved colchicine to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, coronary revascularization, and cardiovascular (CV) death in adult patients with established or established atherosclerotic disease. with multiple risk factors for CV disease .

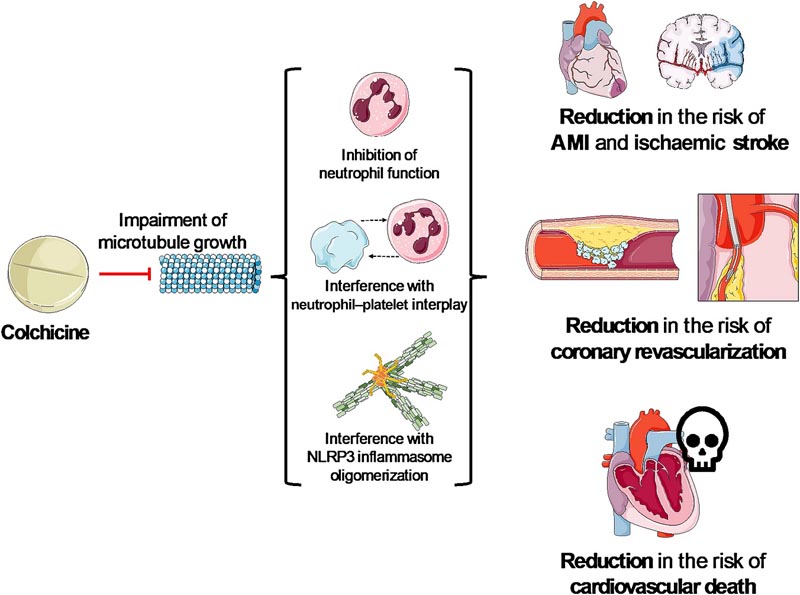

Colchicine was used for centuries to cure gouty arthritis and, more recently, for acute and recurrent pericarditis and autoinflammatory diseases due to its broad anti-inflammatory action that depends on (i) interference with microtubule functions; (ii) alteration of chemotaxis, mobilization and recruitment of neutrophils; (iii) impairment of neutrophil-platelet interaction; and (iv) indirect blockage of NACHT, leucine-rich repeat, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome oligomerization through microtubule interference1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Anti-inflammatory effects of colchicine . Colchicine has anti-inflammatory properties mediated by effects on neutrophils and the NLRP3 inflammasome. In fact, colchicine has recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to reduce cardiovascular risk, particularly to address residual inflammatory risk. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; NLRP3, NACHT, leucine-rich and pyrin domain-containing protein 3

Once represented as a mere accumulation of lipids within the vessel wall, atherosclerosis is now considered an inflammatory disease . Accumulation of proinflammatory lipoproteins in the lumen of arteries causes endothelial dysfunction and is followed by activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and production of the inflammasome-dependent cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18. These events are responsible for the maintenance of endothelial dysfunction, impaired vasodilation, activation and localization of leukocytes, promotion of oxidative stress, and external remodeling of the arterial wall. Interleukin-1β locally stimulates coagulation factors and platelet activation, thereby promoting plaque rupture and thrombosis , and systemically induces the production of IL-6, which through an increase in proinflammatory and procoagulant events, fuels a vicious cycle responsible for the increase in CV events.

Modulation of the NLRP3/IL-1β inflammasome axis has emerged as an attractive therapeutic target to reduce the burden of atherosclerotic disease.

While statins were shown to possess cholesterol-lowering properties and anti-inflammatory effects, reducing the ’risk of residual cholesterol’ , a portion of these patients achieved target low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels but were found to still be at risk. of cardiovascular events due to ’residual inflammatory risk’ . The seminal Canakinumab ANtiinflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study (CANTOS) trial demonstrated that canakinumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks IL-1β, reduced recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with prior myocardial infarction who were aggressively treated with statins and evidence of systemic inflammation. (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein ≥ 2 mg/L), regardless of any impact on lipids.

Consequently, it has been shown that among patients already taking a statin, those with high levels of inflammation, that is, the highest quartiles of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, experienced the greatest risk of future cardiovascular events.

Colchicine was also shown to reduce CV risk in three randomized clinical trials (RCTs): low-dose colchicine (LoDoCo), LoDoCo2, and COLCOT (COLchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial). All these findings clearly highlight that reducing the risk of residual cholesterol with statins (drugs with anti-inflammatory and cholesterol-lowering properties) is not sufficient to reduce CV events such as residual inflammatory risk, i.e., high-sensitivity C-reactive protein ≥ 2 mg/ L: not adequately controlled.

Anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, has also shown promising effects in mitigating the acute inflammatory response in acute myocardial infarction and improving cardiorespiratory status in patients with heart failure and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein ≥ 2 mg/ L. However, unlike colchicine, canakinumab and anakinra, the same beneficial effects were not found with other anti-inflammatories with a different mechanism of action, such as methotrexate, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Colchicine has a series of properties that make this drug promising as an additional pillar in the treatment of patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease along with statins and antiplatelets . In fact, colchicine is administered orally, is inexpensive, and is widely available, which may favor its rapid implementation. It has a good safety profile, with a small but significant increase in infections , particularly pneumonia, but not opportunistic infections. This side effect should be expected considering that blocking the NLRP3 inflammasome may delay the recognition of infections, but does not affect the response to pathogens or tissue repair, as has been widely studied in patients experiencing severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS). -CoV- 2) pneumonia.

Although subject to drug interactions, the most common side effect is diarrhea, which can lead to discontinuation in up to 20% of patients. Muscle and hematologic toxicities are also possible, although they were rarely described in trials testing colchicine 0.5 mg once daily. Finally, given the narrow therapeutic window, extreme attention should be paid to patients with chronic kidney disease .

The dose of colchicine used in the three CV prevention RCTs was 0.5 mg once a day , which is the same dose approved by the FDA, although in some countries the available dose is 0.6 mg. It is implausible that a difference of 0.1 mg could provide large differences in terms of efficacy, side effects or toxicity, although this point remains to be clarified. On the other hand, it is unknown whether higher doses (>0.5 mg per day) may portend greater benefits.

To assign patients to the correct drug, it may be tempting to screen patients for high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and treat only those with high-sensitivity C-reactive protein ≥ 2 mg/L. This remains a topic of debate, but is not supported by the findings, as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein was not measured in the two largest trials with colchicine where clinical benefit was evident across the spectrum of cardiovascular diseases, including patients with asymptomatic coronary artery calcifications and patients with recent myocardial infarction.

The FDA approval of colchicine for secondary CV prevention definitely represents the beginning of a new era, as it is the first approved drug that addresses residual inflammatory risk . The optimal duration of treatment and the extension of its benefits to other inflammatory conditions, such as heart failure, certainly merit specific long-term trials in the near future.