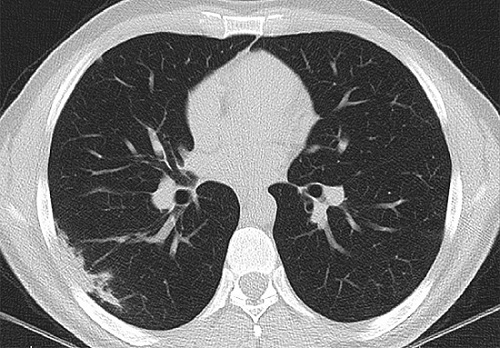

The lung scan was the first sign of trouble. In the early weeks of the coronavirus pandemic, clinical radiologist Ali Gholamrezanezhad began to notice that some people who had cleared their COVID-19 infection still had distinctive signs of damage. “Unfortunately, sometimes the scar never goes away ,” he says.

Gholamrezanezhad of the University of Southern California (Los Angeles) and his team began tracking patients in January using computed tomography (CT) to study their lungs. They followed up on 33 of them more than a month later, and their as-yet-unpublished data suggests that more than a third had tissue death that caused visible scarring. The team plans to follow the group for several years.

These patients likely represent the worst case scenario. Because most infected people don’t end up in the hospital, Gholamrezanezhad says the overall rate of lung damage in the medium term is likely to be much lower; The best estimate of it is that it is less than 10%.

However, given that 28.2 million people are known to have been infected so far and that the lungs are just one of the places where doctors have detected damage, even that low percentage means that hundreds of thousands of people are experiencing consequences. long-lasting for your health.

Doctors are now worried that the pandemic will lead to a significant increase in people struggling with long-term conditions and disabilities. Because the disease is so new, no one knows yet what the long-term impacts will be.

Some of the damage is likely a side effect of intensive treatments such as intubation, while other persistent problems could be caused by the virus itself. But preliminary studies and existing research on other coronaviruses suggest that the virus can damage multiple organs and cause some surprising symptoms.

People with more severe infections may experience long-term damage not only to the lungs, but also to the heart, immune system, brain, and other sites.

Evidence from previous coronavirus outbreaks, especially the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, suggests these effects may last for years. And while in some cases the most serious infections also cause the worst long-term impacts, even mild cases can have life-changing effects, particularly persistent discomfort similar to chronic fatigue syndrome.

Many researchers are now launching follow-up studies of people who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Several of these focus on damage to specific organs or systems; others plan to track a variety of effects. What they find will be crucial to treating those with long-term symptoms and trying to prevent new infections from persisting.

“We need clinical guidelines for what care for COVID-19 survivors should look like,” says Nahid Bhadelia, an infectious disease physician at Boston University School of Medicine, who is setting up a clinic to help people with COVID- 19. "That can’t evolve until we quantify the problem."

Lasting effects

In the early months of the pandemic, as governments scrambled to stop the spread by implementing lockdowns and hospitals struggled to cope with the tide of cases, most research focused on treating or preventing infections. .

Doctors were well aware that viral infections could lead to chronic diseases, but exploring that was not a priority. "At first, everything was acute, and now we’re recognizing that there may be more problems," says Helen Su, an immunologist at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland. "There is a definite need for long-term studies."

The obvious place to check for long-term damage is in the lungs, because COVID-19 starts as a respiratory infection. Few peer-reviewed studies have been published exploring lasting lung damage. Gholamrezanezhad’s team analyzed lung CT images of 919 patients from published studies and found that the lower lobes of the lungs are the most frequently damaged.

The images were riddled with opaque patches indicating inflammation, which could make breathing difficult during sustained exercise. Visible damage usually reduces after two weeks. An Austrian study also found that lung damage decreased over time: 88% of participants had visible damage 6 weeks after being discharged from the hospital, but by 12 weeks, this number had fallen to 56%.

Symptoms may take a long time to disappear ; A study published in August followed people who had been hospitalized and found that even a month after discharge, more than 70% reported shortness of breath and 13.5% were still using oxygen at home.

Evidence from people infected with other coronaviruses suggests that damage will persist for some. A study published in February recorded long-term lung damage from SARS, which is caused by SARS-CoV-1. Between 2003 and 2018, Zhang et al. (Beijing) tracked the health of 71 people who had been hospitalized with SARS. Even after 15 years, 4.6% still had visible lung lesions and 38% had reduced diffusing capacity, meaning their lungs were poor at transferring oxygen into the blood and removing carbon dioxide from the blood. the same.

COVID-19 often attacks the lungs first, but it is not simply a respiratory disease, and in many people, the lungs are not the most affected organ. In part, that’s because cells in many different places harbor the ACE2 receptor , which is the main target of the virus, but also because infection can damage the immune system.

Some people who have recovered from COVID-19 may be left with a weakened immune system.

Many other viruses are thought to do this. "It has long been suggested that people who have been infected with measles are immunosuppressed for a prolonged period and are vulnerable to other infections," says Daniel Chertow, who studies emerging pathogens at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda. Maryland. "I’m not saying that would be the case with COVID, I’m just saying there’s a lot we don’t know." SARS, for example, is known to decrease the activity of the immune system by reducing the production of signaling molecules called interferons.

His and colleagues hope to enroll thousands of people around the world in a project called COVID Human Genetic Effort , which aims to find genetic variants that compromise people’s immune systems and make them more vulnerable to the virus. They plan to expand the study to people with long-term impairment, hoping to understand why their symptoms persist and find ways to help them.

The virus can also have the opposite effect, causing parts of the immune system to become overactive and causing harmful inflammation throughout the body. This is well documented in the acute phase of the disease and is implicated in some of the short-term impacts. For example, it could explain why a small number of children with COVID-19 develop widespread inflammation and involvement of different organs.

This immune overreaction can also occur in adults with severe COVID-19, and researchers want to know more about the side effects once the virus infection has run its course. For Adrienne Randolph of Boston Children’s Hospital, "The question is, in the long term, when they recover, how long does it take for the immune system to return to normal?"

The importance of the matter

An overactive immune system can lead to inflammation, and one particularly susceptible organ is the heart.

During the acute phase of COVID-19, about a third of patients show cardiovascular symptoms, says Mao Chen, a cardiologist at Sichuan University (China). "It’s absolutely one of the short-term consequences."

One such symptom is cardiomyopathy, in which the heart muscles become dilated, stiff, or thickened, affecting the heart’s ability to pump blood. Some patients also have pulmonary thrombosis, in which a clot blocks a blood vessel in the lungs. The virus can also damage the circulatory system more widely, for example by infecting the cells that line blood vessels.

Lung damage (opaque white patch, lower left) may persist for weeks

after initial infection. Credit: Ali Gholamrezanezhad

“My biggest concern is also the long-term impact ,” Chen says. In some patients, she says, the risk to the cardiovascular system "persists for a long time." Chen and her colleagues reviewed pre-pandemic data for a study published in May, noting that people who have had pneumonia have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease 10 years later, although the absolute risk remains small. Chen speculates that an overactive immune system and resulting inflammation might be involved.

The studies are already beginning. In early June, the British Heart Foundation in London announced six research programs, one of which will follow hospitalized patients for six months, tracking damage to the heart and other organs. Data-sharing initiatives such as the CAPACITY registry, launched in March, are collecting reports from dozens of European hospitals on people with COVID-19 who have cardiovascular complications.

Similar long-term studies are needed to understand the neurological and psychological consequences of COVID-19. Many people who become seriously ill experience neurological complications such as delirium, and there is evidence that cognitive difficulties, including confusion and memory loss, persist for some time after acute symptoms have resolved. But it is unclear whether this is because the virus can infect the brain or whether the symptoms are a secondary consequence, perhaps of inflammation.

Chronic fatigue

One of the most insidious long-term effects of COVID-19 is the least understood: severe fatigue.

Over the past nine months, a growing number of people have reported paralyzing exhaustion and malaise after having the virus. Support groups on sites like Facebook host thousands of members; They struggle to get out of bed or work for more than a few minutes or hours at a time.

A study 7 of 143 people with COVID-19 discharged from a hospital in Rome found that 53% had reported fatigue and 43% had shortness of breath 2 months (on average) after their symptoms began. A study of patients in China showed that 25% had abnormal lung function after 3 months, and that 16% were still fatigued.

Paul Garner, an infectious diseases researcher at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, has experienced this first-hand. His initial symptoms were mild, but since then he has experienced "a roller coaster of poor health, extreme emotions and complete exhaustion." His mind became "foggy" and new symptoms appeared almost every day, from difficulty breathing to arthritis in his hands.

These symptoms resemble chronic fatigue syndrome, also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME). The medical profession has struggled for decades to define the disease, leading to a breakdown in trust among some patients. There are no known biomarkers, so it can only be diagnosed based on symptoms. Because the cause is not fully understood, it is not clear how to develop a treatment. Contemptuous attitudes among doctors persist, according to some patients.

People who report chronic fatigue after having COVID-19 describe similar difficulties. On the forums, many say they have received little or no support from doctors, perhaps because many of them showed only mild symptoms, or none at all, and were never hospitalized or in danger of death. It won’t be easy to establish the links between COVID-19 and fatigue with certainty, Randolph says. Fatigue does not seem to be limited to severe cases . It is common in people who had mild symptoms and therefore may not have been tested for the virus.

The only way to find out if SARS-CoV-2 is behind these symptoms is to compare people who are known to have had the virus with those who have not, Chertow says, to see how often fatigue occurs and from what. shape. Otherwise, there is a risk of grouping together people whose fatigue has manifested itself for different reasons and who may need different treatments.

After the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014-16, American researchers collaborated with the Liberian Ministry of Health to conduct a long-term follow-up study called Prevail III . The study identified six long-term sequelae of Ebola, ranging from joint pain to memory loss.

The situation is clearer for people who have been seriously ill with COVID-19, especially those who needed ventilators, Chertow says. In the worst cases, patients experience injuries to the muscles or nerves that supply them and often face “a very long-lasting battle on the order of months or even years” to regain their previous health and fitness. says.

Again, there is evidence from SARS that coronavirus infection can cause long-term fatigue. In 2011, researchers at the University of Toronto described 22 people with SARS, all of whom were still unable to work 13 to 36 months after infection. Compared to controls, they had persistent fatigue, muscle pain, depression and sleep disorders.

Another study, published in 2009, tracked people with SARS for 4 years and found that 40% had chronic fatigue. Many were unemployed and had experienced social stigmatization.

It’s unclear how viruses can cause this damage, but a 2017 review of the literature on chronic fatigue syndrome found that many patients have persistent low-grade inflammation , possibly triggered by infection. If COVID-19 is a trigger, a wave of psychological effects "may be imminent", write a group of researchers from St Patrick’s Mental Health Services in Dublin.

In many countries, the pandemic shows no signs of abating and health systems are already able to respond to acute cases. However, researchers say it is crucial to start investigating the long-term effects now. But the answers won’t come quickly. "The problem is," says Gholamrezanezhad, "that to evaluate the long-term consequences, what is needed is time."