More than 2 years after the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic, the global population has a heterogeneous immunological background resulting from various exposures to infections, viral variants, and vaccination. Evidence at the level of binding and neutralizing antibodies and B cell and T cell immunity suggests that a history of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection may have a negative effect on subsequent protective immunity. In particular, the immune response to the B.1.1.529 (omicron) subvariants could be compromised by differential immune imprinting in people who have had a previous infection with the original virus or the B.1.1.7 (alpha) variant.

We investigated the epidemiological evidence of immune imprinting in people with a specific immune history related to a natural infection. We assessed the incidence of repeat reinfection in the national cohort of people in Qatar who had had a documented omicron BA.1 or BA.2 reinfection after a primary infection with non-omicron SARS-CoV-2 (the “double-priming” cohort ) in comparison with the incidence of reinfection in the national cohort of people who had a documented primary infection with omicron BA.1 or BA.2 (the "omicron-primed" cohort ). This analysis was performed as a matched retrospective cohort study (Section S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org).

Data on SARS-CoV-2 laboratory testing, clinical infection, vaccination, and demographic characteristics were extracted from Qatar’s national SARS-CoV-2 databases. Individuals in both cohorts were exactly matched in a 1:3 ratio based on sex, 10-year age group, nationality, number of coexisting conditions, and calendar week of omicron subvariant infection. The follow-up period began 90 days after documentation of omicron subvariant infection. Vaccinated people were excluded. Associations were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression models. Hazard ratios were adjusted for the factors used for matching.

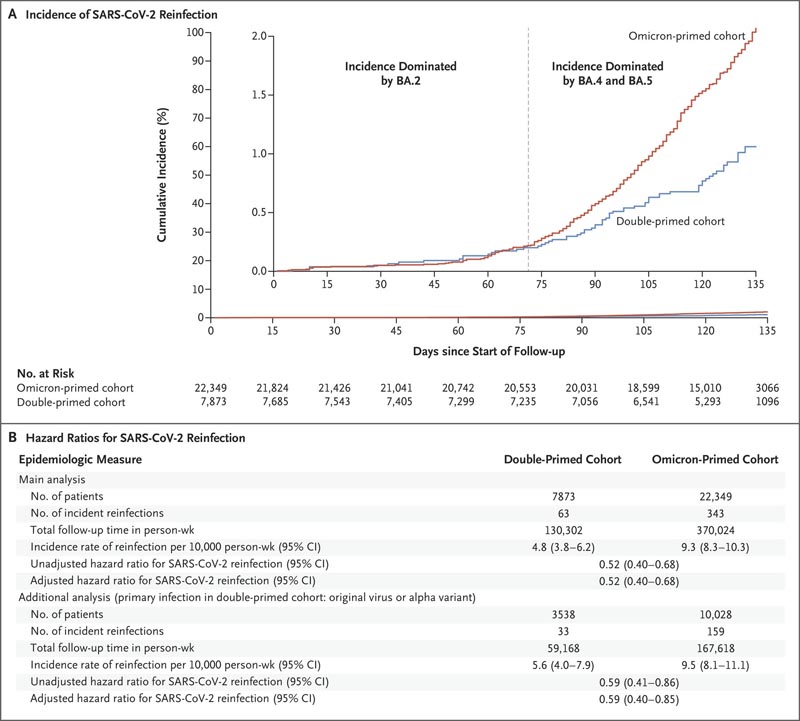

The matched cohorts included 7873 people in the double-primed cohort and 22,349 people in the omicron-primed cohort. The study population was representative of the unvaccinated population of Qatar with respect to demographic characteristics and history of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

During follow-up, 63 reinfections occurred in the double-primed cohort and 343 in the omicron-primed cohort; none of the infections progressed to severe, critical or fatal Covid-19. At 135 days from the start of follow-up, the cumulative incidence of reinfection was 1.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.8 to 1.4) in the double-vaccinated cohort and 2.1 % (95% CI, 1.8 to 2.3) in the omicron-primed cohort (Figure 1A).

In the comparison of the complete matched double-primed cohort with the omicron-primed cohort, the adjusted hazard ratio for reinfection was 0.52 (95% CI, 0.40 to 0.68). In an analysis involving the subgroup of people in the double-priming cohort whose primary infection was with the parent virus or the alpha variant compared with the omicron-primed cohort, the adjusted hazard ratio for infection was 0.59 ( 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.85).

Figure 1. Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection in the double-primed and Omicron-primed cohorts. The double-priming cohort included individuals with documented reinfection with B.1.1.529 (omicron) subvariant BA.1 or BA.2 following a primary infection with pre-omicron severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). ), and the omicron-primed cohort included individuals with a documented primary infection with an omicron BA.1 or BA.2 subvariant. The inset in Panel A shows the same data on an expanded y-axis. The main analysis included the complete matched cohorts; In an additional analysis (Panel B), the double-priming cohort included only people whose primary infection had been with the original virus or the B.1.1.7 (alpha) variant. Hazard ratios were adjusted for the factors used for matching. This study was conducted in Qatar between December 19, 2021 and August 15, 2022. Follow-up began 90 days after documentation of reinfection.

In the first 70 days of follow-up, when infections were dominated by the BA.2 subvariant, 2.3 the adjusted hazard ratio for infection was 0.92 (95% CI, 0.51 to 1.65) . However, the cumulative incidence curves diverged when subvariants BA.4 and BA.5 were introduced and subsequently 4 dominated (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.62) (Figure 1A).

Limitations of the study are discussed in Section S1. A potential limitation was the difference in testing frequencies between the two cohorts, but a sensitivity analysis with adjustments for these differences showed similar results to the main analysis.

Omicron infection induces strong protection against subsequent Omicron infection.

In the present cohort study, we found that additional prior infection with non-omicron SARS-CoV-2 strengthens this protection against subsequent omicron infection. Previous pre-omicron infection may have amplified the immune response against a future reinfection challenge.