University of Colorado Denver

Highlights

Summary Trunk flexion is an understudied biomechanical variable that potentially influences running performance and injury susceptibility. We present and test a theoretical model that relates trunk flexion angle to stride parameters, joint moments, and ground reaction forces that have been implicated in repetitive strain injuries. Twenty-three participants (12 men, 11 women) ran with preferred trunk flexion and three more trunk-flexed positions (moderate, intermediate, and high) on a custom-built Bertec™ instrumented treadmill while simultaneously capturing kinematic and kinetic data. Markers attached to bony landmarks tracked movement of the trunk and lower extremity. Stride parameters, moments of force and ground reaction force were calculated using Visual 3D software (C-Motion ©). From preferred to high trunk flexion, stride length decreased by 6% (P < 0.001) and stride frequency increased by 7% (P < 0.001). Hip extensor moments increased 70% (P < 0.001), but knee extensor moments (P < 0.001) and ankle plantarflexor moments (P < 0.001) decreased 22% and 14%, respectively. Greater trunk flexion increased loading rate by 29% (P < 0.01) and vertical ground reaction force impacts transients by 20% (P < 0.01). Trunk flexion angle during running has significant effects on stride kinematics, lower extremity joint moments, and ground reaction force and should be further investigated in relation to running performance and injury. by repetitive efforts. |

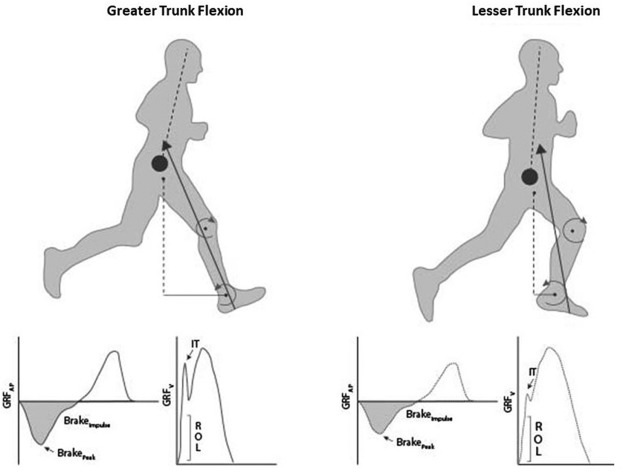

Illustrates the biomechanical model that relates trunk flexion to the kinetics and kinematics of the lower extremities. Greater trunk flexion is expected to increase stride at the hip due to a more forward placement of the foot relative to the body’s center of mass; increase stride length and decrease stride frequency; increase hip extension moments but decrease knee and ankle moments, as the external force vector aligns more closely with the knee and ankle joint; increase braking force, rate of load (RoL) and impact transient peaks (IT). Reducing trunk flexion will have the opposite effect on all parameters.

Comments

The ubiquitous overuse injuries that plague runners may be due to a little-thought-out culprit: how much you lean forward .

Trunk flexion , the angle at which a runner leans forward from the hips, can vary greatly: Runners have self-reported angles from about -2 degrees to more than 25.

A new study from the University of Colorado Denver (CU Denver) found that greater trunk flexion has a significant impact on stride length, joint movements, and ground reaction forces. The way you bend may be one of the contributing factors to knee pain, medial tibial stress syndrome, or back pain.

"This was a nuisance that turned into a study," said Anna Warrener, PhD, lead author and assistant professor of anthropology at CU Denver. Warrener worked on the initial research during her postdoctoral fellowship with Daniel Liberman, PhD, in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University. "When [Lieberman] was preparing for his marathons, he noticed that other people were leaning too far forward while running, which had many implications for their lower limbs. Our study was built to find out what they were."

The study was published in Human Movement Science .

A New Angle on Overuse Injuries

The head, arms and trunk make up approximately 68% of the total body mass.

Small changes in trunk flexion have the potential to substantially alter lower extremity kinematics and ground reaction forces (GRFs) during running.

To study the aftereffects, Warrener and his team recruited 23 injury-free recreational runners between the ages of 18 and 23. They recorded each participant running 15-second trials in their self-selected trunk position and three others: a 10-, 20 and a flexion angle of 30 degrees. But for the study to work, they first had to figure out how to get each runner to bend at the correct incline.

"We had to create a way that we could reasonably force someone to lean forward that wouldn’t make them so uncomfortable that they would change everything about their gait," Warrener said. The team hung a lightweight plastic peg from the ceiling just above the runners’ heads, moving it up or down depending on the angle needed.

Contrary to the team’s original hypothesis, mean stride length decreased by 13 cm and stride frequency increased from 86.3 strides/min to 92.8 strides/min. Relative hip lead increased by 28%.

"The relationship between strike frequency and stride length surprised us," Warrener said. "We thought that the more you lean forward, your leg would need to extend further to prevent your body mass from falling outside the support zone. As a result, stride and lunge frequency would increase. The opposite was true. and stride rate increase".

Warrener believes this may have been due to a decrease in the aerial phase (if they are not in the air as much, runners will take shorter steps), meaning that leg movements were sped up as a result of reduced forward motion. .

"The act of swinging your leg is really costly while running," Warrener said. "Spinning it faster while leaning forward can mean higher locomotor cost."

Compared to participants’ natural trunk flexion, increasing angles led to a more flexed hip and a bent knee joint. A larger incline also changed the position of the runners’ foot and lower extremities, resulting in greater GRF impact on the body (loading rate by 29%; vertical ground reaction force impact transients by a twenty%).

Combining trunk flexion angle, foot and leg placement, and GRF variables shows that excessive trunk flexion could be one of the causes of detrimental running form and, according to Warrener, is key to understanding how The various forms of racing optimize economy and performance.

"The big picture is that running isn’t just about what happens from the trunk down, it’s a whole-body experience ," Warrener said. "Researchers should think about the aftereffects of trunk flexion when studying running biomechanics."

Conclusions Excessive trunk flexion angles during steady-state running have long been considered undesirable for good running form. Trunk flexion is necessary for initial acceleration of the body, however, fatigue can increase trunk flexion angles with potentially harmful effects and individual variation. in trunk posture often has no clear cause. Whatever its origin, variation in trunk flexion has been shown to influence running economy and performance and has been directly and indirectly associated with other aspects of running form that are thought to cause injuries such as pain. knee, medial tibial stress syndrome and back pain. Given the correlated effects between trunk flexion angle, foot and leg placement, and GRF variables demonstrated in this study, it is reasonable to assume that excessive trunk flexion could be a cause of an injurious form of running and is of key importance in understanding how various career forms are optimized. economy and performance. |