Highlights Among patients hospitalized with COVID-19, those with psychiatric illnesses have a 1.5 times higher risk of death not explained by medical comorbidities. Psychiatric illness is associated with increased medical morbidity and mortality, in addition to medical comorbidity. These researchers used administrative data from a US hospital system to examine mortality in COVID-19 patients as a function of psychiatric illness. Of 1,685 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in February, March and April, 318 died in May. Overall, 473 (28%) had a psychiatric diagnosis before hospitalization. Having a psychiatric diagnosis was associated with higher odds of being female, older, and white, and having medical comorbidities. In unadjusted analyses, mortality in the psychiatric subgroup was 2.3 times higher than in the rest of the cohort. The rates at 2, 3 and 4 weeks were 36% vs. fifteen%; 41% vs. 22%; and 45% vs. 32%, respectively. In analyzes controlling for demographics and medical comorbidities, the risk of death in patients with psychiatric diagnoses remained elevated (hazard ratio, 1.5). Comment High mortality rates in psychiatric patients are well documented and cannot be explained by comorbid medical illness. The effect has been attributed to poor health habits, use of psychotropic medications, or hypothetical neurobiological mechanisms of psychiatric illness, including inflammatory processes and compromised immune function. This study is limited by the use of diagnosis codes to identify psychiatric illnesses and the absence of information on individual diagnoses, health habits, psychiatric treatment, and COVID-19 treatments. However, the findings highlight the vulnerability of this population in addition to medical comorbidities, information that could be useful to hospitalists formulating COVID-19 treatment plans for this subgroup. |

Psychiatric disorders are associated with a shorter life expectancy (i.e., a reduction of up to 10 years). There is concern that psychiatric comorbidity may increase mortality related to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), as suggested by previous preliminary studies of heart disease and infectious disease outcomes.

A large population-based study in Denmark suggested that an a priori diagnosis of depression was associated with higher 30-day mortality for those hospitalized with an infection. Here, we evaluated the association between having any prior psychiatric illness diagnosis and COVID-19-related mortality of patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Methods

This cohort study was conducted at Yale New Haven Health System, a five-hospital system in the northeastern United States. Data were obtained from Epic Systems and included all COVID-19-positive inpatient encounters between February 15 and April 25, 2020, and followed through May 27, 2020 to determine mortality.

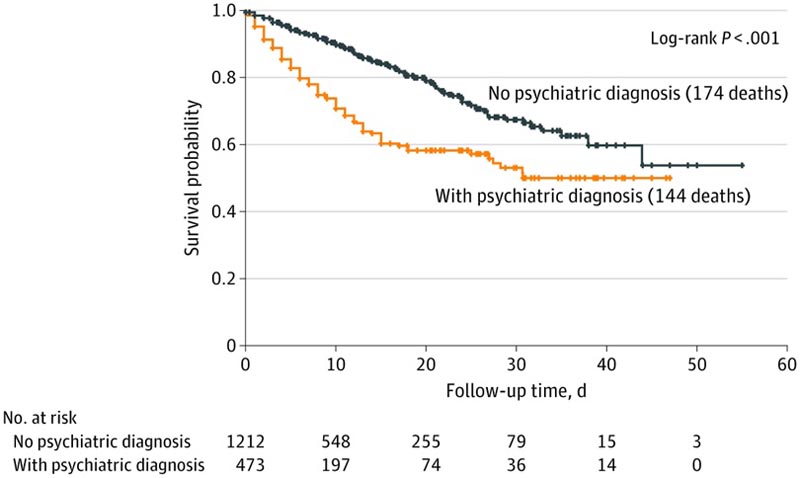

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize these patients with or without a previous psychiatric diagnosis. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to compare survival rates using the log-rank test. Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression was used to evaluate the association of pretreatment risk factors (including age, sex, race/ethnicity, medical comorbidities, and hospital location) with mortality.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed to confirm the association of psychiatric comorbidities with mortality after controlling for other risk factors. All analyzes were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), testing a two-sided significance level of .05.

The Yale New Haven Health System institutional review board approved exemption from the study and a waiver of consent was granted. The study used de-identified data and was considered a medical record, institutional review board review only. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

Results

A total of 1685 patients were hospitalized with COVID-19 during the study period (mean [SD] age, 65.2 [18.4] years; 887 [52.6%] were men). Of the 1685 patients, 473 (28%) received psychiatric diagnoses before hospitalization.

Patients with psychiatric diagnoses were significantly older and more likely to be female, white and non-Hispanic and to have medical comorbidities (malignant cancer, cerebrovascular disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, myocardial infarction and/or HIV) .

In total, 318 patients (18.9%) died . Patients with a psychiatric diagnosis had a higher mortality rate compared to those without a psychiatric diagnosis (Figure 1), with 35.7% vs 14.7% 2-week mortality and 40.9% vs 22.2% 3 weeks mortality (p <0.001) (and with 44.8% versus 31.5% mortality rate at 4 weeks).

Median follow-up was 8 days (interquartile range, 4-16 days). In the unadjusted model, the risk of COVID-19-related in-hospital death was higher for those with any psychiatric diagnosis (hazard ratio, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.8-2.9; P < 0.001) .

After controlling for demographic characteristics, other medical comorbidities, and hospital location, the risk of death remained significantly higher among patients with a psychiatric disorder (hazard ratio, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-1 .9; p = 0.003).

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to characterize the association of psychiatric diagnosis with COVID-19-related mortality. The main finding is that patients with a prior psychiatric diagnosis while hospitalized for COVID-19 had a higher mortality rate compared to those without a psychiatric condition. The finding is similar to previous findings: people with concurrent medical and psychiatric diagnoses had worse outcomes and higher mortality.

It is unclear why psychiatric illness predisposes to COVID-19-related mortality. Psychiatric symptoms may arise as a marker of systemic pathophysiological processes , such as inflammation, which in turn may predispose to mortality. Similarly, psychiatric disorders may increase systemic inflammation and compromise immune system function, while psychotropic medications may also be associated with mortality risk.

Limitations of the study include the fact that people who were not hospitalized for COVID-19 or who died outside the hospital were not used in the analysis. Additionally, diagnosis codes were used to assess any psychiatric diagnosis, regardless of psychiatric treatment status (patient with active psychiatric disorder, in remission, or recovered). The data also does not include information on COVID-19 treatment.