Summary Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is a common cause of lateral hip pain and encompasses a spectrum of disorders, including trochanteric bursitis, abductor tendon pathology, and external coxa saltans . Greater trochanter pain syndrome is primarily a clinical diagnosis, and careful clinical examination is essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment. A complete history and physical examination can be used to help differentiate greater trochanteric pain syndrome from other common causes of hip pain, such as osteoarthritis, femoroacetabular impingement, and lumbar stenosis. Although not required for diagnosis, plain radiographs and MRI may be useful in excluding alternative pathologies or guiding treatment of greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Most patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome respond well to conservative treatment , including physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and corticosteroid injections. Surgical management is generally indicated in patients with chronic symptoms refractory to conservative therapy. A wide range of surgical options, both open and endoscopic, are available and should be guided by the specific etiology of the pain. |

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome ( GTPS) is a general term used to describe disorders of the peritrochanteric space, including trochanteric bursitis, abductor tendon pathology, and external coxa saltans. GTPS is a common cause of lateral hip pain and tenderness, with an annual incidence of up to 1.8 per 1000 adults in the primary care setting. Although GTPS is observed in all age groups, it most frequently affects patients between the fourth and sixth decades of life, with a female predominance.

Although conservative treatment is effective for most patients with GTPS, many show symptoms refractory to physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and corticosteroid injections (CSI). Given the heterogeneous nature of GTPS, accurate diagnosis of the specific etiology of GTPS and the degree of gluteal tendon injury is critical to guide appropriate treatment. The purpose of this review is to highlight clinical and radiographic findings that can differentiate GTPS from other causes of lateral hip pain and guide management. In addition, the indications, techniques and results for operative and conservative treatment are described.

Methods

Two authors (MAP and JS) searched PubMed/MEDLINE using the terms “greater trochanter pain syndrome,” “trochanteric bursitis,” and “gluteal tendinopathy.” The search was not restricted by date until February 17, 2021.

Etiology and risk factors

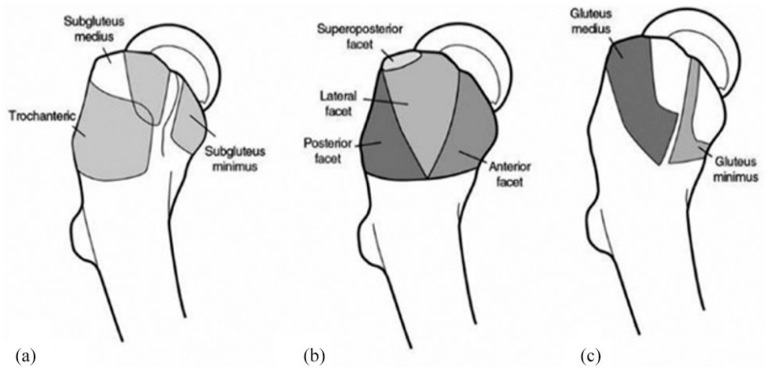

Historically, most patients presenting with pain and tenderness in the lateral hip were diagnosed with trochanteric bursitis , which refers to inflammation of the subgluteal bursa located deep to the iliotibial band (ITB) and tendons. abductors (Figure 2). However, radiographic and histopathological studies have shown that the trochanteric pouches are rarely affected in isolation; rather, bursal strain is more commonly associated with abductor tendinopathy .

Figure : Anatomy of the greater trochanter. (a) Three peritrochanteric bursae, (b) bony facets of the greater trochanter, and (c) insertion sites of the abductor tendons.

GTPS is thought to develop from friction of the iliotibial band (ITB) on the greater trochanter, leading to regional microtrauma with overuse. As noted above, hip abductor tendinopathy is commonly implicated in GTPS. Findings of tendon degeneration and associated bursitis in the abductor apparatus of the hip have invited comparisons with rotator cuff tendinopathy of the shoulder as a possible analogous pathological process, with eventual progression to partial- and full-thickness tendon tears.

External coxa saltans , or external snapping hip, is characterized by a palpable clicking of the ITB or gluteus maximus as it moves from posterior to anterior over the greater trochanter with hip flexion and from anterior to posterior with hip flexion. extension. This is often attributed to thickening of the posterior aspect of the ITB or the anterior edge of the gluteus maximus, and repeated clicking can lead to irritation of the trochanteric bursa, gluteal tendinopathy, and consequently lateral hip pain. Less commonly, GTPS may result from blunt trauma to the hip or iatrogenic injury during hip arthroplasty.

Several risk factors have been associated with GTPS, including increasing age, obesity, osteoarthritis of the knee or hip, low back pain, and leg length discrepancy. These findings suggest that altered limb mechanics and abnormal force vectors at the hip likely contribute to the development of GTPS. Similarly, the higher prevalence of GTPS in women is thought to be related to differences in the size and shape of the pelvis, with wider trochanters creating greater stress on the ITB. GTPS has also been associated with less bone restriction of the hip, where instability can contribute to greater tension in the gluteal muscles. Patients reporting high levels of pain show significantly impaired hip stability relative to those reporting lower levels of pain.

History and physical examination

GTPS classically presents as chronic lateral hip pain in the region of the greater trochanter that may radiate to the buttock or over the lateral thigh to the knee. The pain is often described as deep and persistent and is exacerbated by lying on the affected side, squatting, sitting with the ipsilateral leg crossed, and climbing stairs. Although rare, patients with GTPS after blunt trauma are likely to report a history of injury or present with ecchymosis or hematoma of the lateral hip. A history of abductor weakness after hip arthroplasty may represent an iatrogenic injury to the abductor tendons or superior gluteal nerve. Psychosocial factors have been shown to affect symptom severity in patients with GTPS and should be evaluated and addressed.

A complete physical examination of the lumbar spine, hips, and knees is essential to reduce the differential in patients presenting with hip pain. Palpation of the posterolateral region of the greater trochanter classically causes focal tenderness in patients with GTPS, as this coincides with the anatomic footprint of the gluteus medius on the posterosuperior aspect of the greater trochanter.

The flexion, abduction, and external rotation (FABER) test, the Ober test, and resisted abduction (figure) may also cause trochanteric pain or tenderness. Patients should be evaluated for a Trendelenburg sign during ambulation or one-legged stance (Figure) which may indicate abductor weakness . Single-leg stance, which was considered positive with pain reproduction within 30 s, had a sensitivity of 38% and specificity of 100% for GTPS.

Figure . Evaluation of hip abductor strength. The patient lies in the lateral decubitus position with the affected side facing up. With the hip and knee extended, the examiner asks the patient to perform resisted hip abduction .

Figure . Trendelenburg test . From (a) standing position, (b) the patient is asked to stand on the affected leg and lift the contralateral foot off the ground. The test is considered positive if the contralateral pelvis tilts downward, indicating abductor weakness .

Clinical evaluation of GTPS should also focus on determining the specific etiology and severity to inform appropriate management.

Patients with external coxa saltans often have a palpable, and in some cases observable, clicking of the ITB over the greater trochanter. While patients commonly volunteer to reproduce the click, the examiner can reproduce it by placing the patient in the lateral decubitus position and palpating the greater trochanter while the patient actively flexes the hip. The diagnosis is confirmed if the clicking stops while pressure is applied to the ITB at the level of the greater trochanter.

Abductor tendon tears often present with abnormal gait and weak hip abduction. In a review of 24 patients with a clinical diagnosis of GTPS, Bird et al. found that the Trendelenburg sign is the most sensitive (73%) and specific (77%) clinical test in the diagnosis of partial and full thickness tears of the gluteus medius tendon. The presence of a Trendelenburg sign has also been associated with an increased need for surgical intervention. Lequesne et al. They similarly found that the single-leg position has a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 97% in the diagnosis of refractory chronic GTPS due to abductor tendon tears.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of lateral hip pain is broad. Intra-articular sources include osteoarthritis, avascular necrosis, labral tears, femoroacetabular impingement, femoral neck stress fractures, and loose bodies. While intra-articular hip pain is often referred to the groin , anterior thigh, and knee, a retrospective analysis of 51 patients with evidence of an intra-articular source of pain found that 27% of patients experienced referred pain over the side of the thigh. It is particularly important to distinguish pain associated with osteoarthritis from GTPS given that these conditions are often comorbid.

In addition to GTPS, extra-articular causes of lateral hip pain include lumbar stenosis and meralgia paresthetica. Lower extremity r adiculopathy resulting from lumbar stenosis can be difficult to distinguish from GTPS; the pattern of referred pain in GTPS may overlap with the distribution of dermatomes L2-4; and stenosis can similarly lead to abductor weakness with a Trendelenburg gait.

The prevalence of GTPS among patients referred to orthopedic spine centers for low back pain is as high as 51%. Lumbar stenosis can be clinically differentiated from GTPS by other characteristic features, including low back pain, paresthesias, focal weakness, radicular pain in the lower extremities, and lack of tenderness over the greater trochanter.

Meralgia paresthetica describes neuropathy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and presents with pain, numbness, and dysesthesia in the anterolateral hip and thigh. Clinical signs that differentiate meralgia paresthetica from GTPS include tenderness over the lateral inguinal ligament and the presence of Tinel’s sign medial and inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine. Administration of a local anesthetic nerve block may help confirm the diagnosis of meralgia paresthetica.

Images

Although GTPS is typically a clinical diagnosis , radiographs are routinely obtained to exclude alternative or concomitant pathology, such as osteoarthritis, femoroacetabular impingement, or lumbar spondylosis. Irregularities on the surface of the greater trochanter and calcifications of the gluteal tendon have been described in patients with GTPS. Plain radiographs are primarily useful for the diagnosis of alternative sources of hip pain, including osteoarthritis, avascular necrosis, femoroacetabular impingement, and lumbar spondylosis.

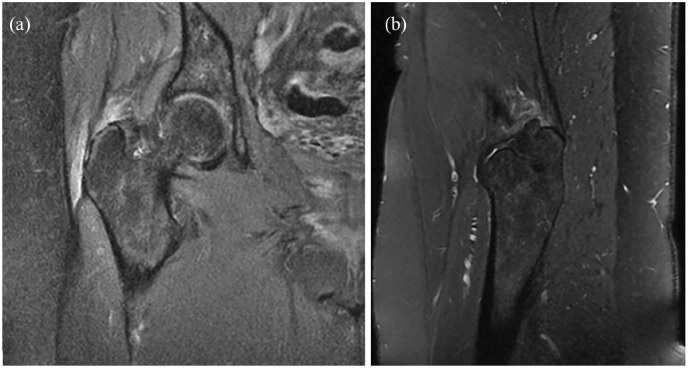

MRI represents the gold standard imaging modality for the diagnosis of GTPS, as studies have consistently demonstrated strong correlations between image interpretation and intraoperative findings . In a retrospective evaluation of 74 hips, Cvitanic et al. 36 reported that MRI is 91% accurate in diagnosing abductor tears, with a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 92%. Characteristic findings of complete gluteal tendon tears include tendon rupture with or without retraction, muscle atrophy, and fatty degeneration. Partial tears exhibit tendon attenuation or thinning on T1-weighted images and associated increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images.

Tendinopathy in the absence of tears is characterized by thickening of the tendon or increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Associated bursal involvement is characterized by bursal distension and inflammation. Importantly, evidence of peritrochanteric edema and bursal fluid on MRI is commonly present in asymptomatic hips , with detection rates as high as 65% to 88%. This underlines the importance of a complete clinical evaluation in the diagnosis of GTPS. Given the variable pathology of GTPS, it is recommended to obtain an MRI and correlate it with clinical findings before proceeding with surgical treatment.

Figure (a) Coronal fat-suppressed proton density and (b) sagittal T2-weighted sequences on MRI of the right hip showing a high-grade partial tear of the gluteus medius and minimus tendons with tendinosis and bursitis underlying trochanteric. The patient gave consent for the publication of this image .

Ultrasonography has also been shown to be effective in the diagnosis of GTPS, with a sensitivity of 79% and 61% for the diagnosis of gluteal tendon tear and bursa pathology, respectively. Characteristic findings of gluteal tendon tears include partial- or full-thickness anechoic defects within the tendon. There may also be loss of muscle mass and increased echogenicity due to fatty degeneration. Tendinosis is characterized by heterogeneous echogenicity and thickening of the tendon with or without calcifications. Additionally, accumulations of bursal fluid and thickening may be observed. Dynamic evaluation with ultrasound may also be useful in the workup of lateral hip pain, including confirmation of the diagnosis of external coxa saltans . Ultrasound evaluation offers several advantages, including low cost and the ability to accurately localize and administer corticosteroids.

Non-operative management

First-line treatment of GTPS is conservative in nature and most patients respond to a combination of activity modification, physical therapy, NSAIDs, and corticosteroid injection (ICS) . Fury et al. reported on a group of 33 GTPS patients treated conservatively for a minimum of 6 months and found significant improvements in mean pain and visual analogue scale (VAS) scores for up to 12 months. Additionally, five of the six patients who worked in occupations requiring intensive physical activity were able to resume their previous employment. Mellor et al. 44 found that 79% of patients treated with activity modification and exercise therapy reported an overall improvement in their condition at one year compared with 52% of patients treated with observation alone.

In a systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of corticosteroid injection (CSI) in the treatment of GTPS, rates of pain improvement and return to baseline activity level ranged from 49% to 100%. In summary, injections appear to be an effective and safe treatment for GTPS and are associated with a low complication rate, with local pain, skin irritation, and swelling being the most commonly reported complications.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy ( ESWT) has shown promising results in several studies.

Evidence supporting the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections in the treatment of GTPS is limited. In a systematic review of five articles and four published abstracts of 209 patients treated with PRP injections, Ali et al. concluded that PRP represents a potentially viable treatment, although current evidence is based on small sample and low quality studies.

Surgical management

Surgical management of GTPS is generally reserved for patients with persistent symptoms for a minimum of 6 to 12 months and who remain refractory to conservative therapy. Before surgery, an MRI should be obtained to guide appropriate management for the specific source of pain. Several case series have described open and endoscopic bursectomy with or without ITB release for the treatment of trochanteric bursitis and gluteal tendinopathy with good results. A similar surgical technique has been described for external coxa saltans . For partial and full thickness tears of the abductor tendons, open and endoscopic bursectomy and tendon repair have been described. Tendon augmentation with allografts or muscle transfer is usually reserved for cases of significant tendon retraction or severe muscle atrophy.

Conclusion

|