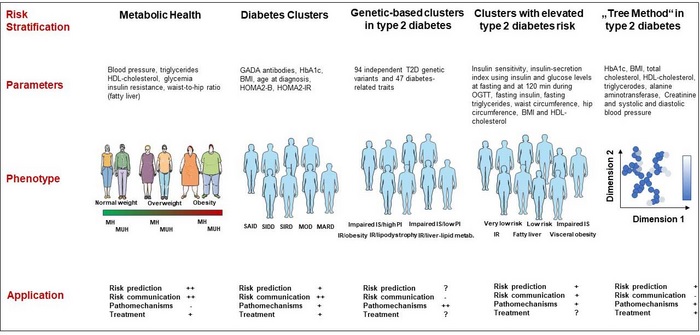

Summary Among the top 20 global risk factors for years of life lost in 2040, baseline forecasts point to three metabolic risks (high blood pressure, high BMI, and high fasting plasma glucose) as the main risk variables. Based on these and other risk factors, the concept of metabolic health is attracting much attention in the scientific community. It focuses on the aggregation of important risk factors, allowing the identification of subphenotypes, such as metabolically unhealthy normal weight people or metabolically healthy obese people, who differ greatly in their risk for cardiometabolic diseases. Since 2018, studies using anthropometry, metabolic characteristics, and genetics in the framework of cluster analysis proposed new metabolic subphenotypes among high-risk patients (e.g., those with diabetes). The crucial point now is whether these subphenotyping strategies are superior to established cardiometabolic risk stratification methods with respect to the prediction, prevention, and treatment of cardiometabolic diseases. In this review, we carefully address this point and conclude, first, with respect to cardiometabolic risk stratification, in the general population, both the metabolic health concept and cluster approaches are not superior to risk prediction models. established. However, both subphenotyping approaches could be informative in improving cardiometabolic risk prediction in subgroups of individuals, such as those in different BMI categories or people with diabetes. Second, applicability of the concepts by treating physicians and communication of cardiometabolic risk to patients is easier using the concept of metabolic health. Finally, approaches to identifying particular cardiometabolic risk groups have provided some evidence that they could be used to assign individuals to specific pathophysiological risk groups, but whether this assignment is useful for prevention and treatment remains to be determined. |

Lean and metabolically unhealthy people have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than the risk seen in obese and metabolically healthy people. The new cluster analyzes also identified large heterogeneity in the risk of type 2 diabetes and CVD and their response to treatment .

Comments

Lean and metabolically unhealthy people have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than the risk seen in obese and metabolically healthy people. Recently, new cluster analyzes (computer-based grouping of people) also identified large heterogeneity in the risk of type 2 diabetes and CVD and their response to treatment. These findings reveal that there may be a huge, as yet undetected, treasure to be discovered in the field of cardiometabolic research.

In a review article in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology , Norbert Stefan of Helmholtz Munich, the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD) and the University of Tübingen, and Matthias B. Schulze of the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbruecke and the DZD highlight how these novel risk stratification concepts can help better implement precision medicine into clinical practice.

Among the top 20 global risk factors for years of life lost in 2040, the three metabolic risks ( high blood pressure, high BMI, and high fasting plasma glucose ) will be the main risk variables. Based on these and other established risk factors, such as low HDL cholesterol and high triglycerides, the concept of metabolic health is attracting much attention in the scientific community. It focuses on the aggregation of important risk factors, allowing the identification of impaired metabolic health. To date, in most of the more than 1,000 studies addressing this topic, people are considered metabolically healthy if they have fewer than 2 of the following metabolic risk factors: high blood pressure, high plasma glucose, low HDL cholesterol and high triglycerides, or drug treatments for these conditions—are present . Thus, subphenotypes were identified , such as metabolically unhealthy normal weight (MUHNW) and metabolically healthy obese (MHO) individuals, which differ greatly in their CVD risk.

In a meta-analysis, Matthias Schulze, Norbert Stefan, and colleagues found that compared to people with metabolically healthy normal weight (MHNW), the risk of CVD increases by 45% in people with MHO and by 100% in people with MUHNW. In their present review article, Norbert Stefan and Matthias Schulze not only summarize the knowledge on these relationships, but also highlight their novel definition of metabolic health . Taking into account the risk factors hypertension, diabetes, and a high waist-to-hip ratio, they found in two very large studies (US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III and UK Biobank) that the risk of mortality for CVD increased by 100% in people with MUHNW, but did not increase in people with MHO. Matthias Schulze emphasizes that “these data reveal the importance of considering the impact of body fat distribution for the definition of metabolic health.”

Norbert Stefan adds: "Do the new cardiometabolic risk groups also help to identify subgroups of people with a different risk of cardiometabolic diseases?" To answer this question, the authors of the present review article discuss the findings of the most important data dimensionality reduction approaches that can be summarized under the term “cluster analysis.”

These studies were primarily conducted in patients with diabetes or in people at risk for type 2 diabetes. Group approaches also rely on routinely available clinical variables, but may include more complex data, such as genetics. Among the subgroups derived from these cluster analyzes are people who predominantly have low insulin secretion, insulin resistance, fatty liver, visceral obesity, mild age-related diabetes, mild obesity-related diabetes, or other more phenotypes. complex.

Norbert Stefan and Matthias Schulze conclude: “With regard to cardiometabolic risk stratification, both the metabolic health concept and group approaches are not considered superior to established risk prediction models. However, both approaches may be informative to better predict cardiometabolic risk in subgroups, such as individuals in different BMI categories or people with type 2 diabetes.’ They also highlight that the applicability of the concepts by treating physicians and the communication of cardiometabolic risk with patients may be easier for the concept of metabolic health. The authors then note that being metabolically healthy or unhealthy , or being assigned to a specific cardiometabolic risk group, will in most cases be a transient assignment . Furthermore, they conclude that approaches to identifying cardiometabolic risk groups have provided evidence that they could be used to assign individuals to specific pathophysiological risk groups. The extent to which this assignment could improve risk assessment and response to treatment remains to be carefully studied.