| 1. Introduction |

Cardiometabolic disease ( CMD) is a clinical syndrome in which there is a causal relationship between metabolic abnormalities and cardiovascular pathology. There are a variety of diseases and conditions classified as NDEs, including obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and cardiovascular disease (CVD). There is a complex interplay of changes in eating behavior, suboptimal nutrition, and air pollution that have contributed to the transformation of NDE from a phenomenon in high-income countries to a global health crisis, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Evidence shows that the combination of NDE and an unfavorable lifestyle can lead to more than doubling the risk of death. Because everyone needs to eat and drink daily and because nutrition affects almost every physiological process in the body, dietary strategies are currently the most basic and feasible lifestyle interventions to improve cardiometabolic health.

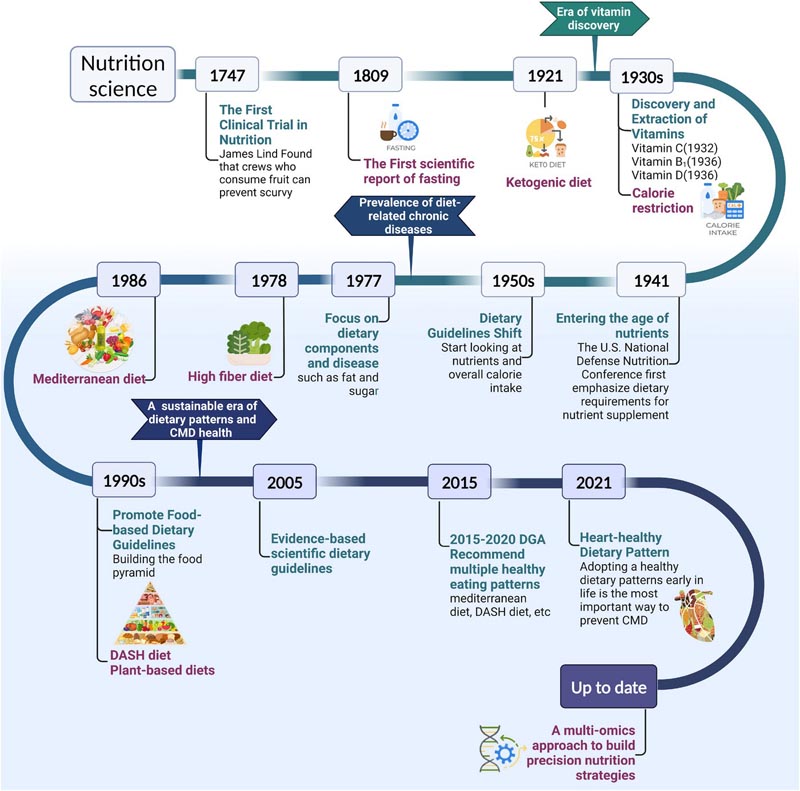

We have only had an understanding of food and disease for a few hundred years, as shown in Figure 1. Since the 1970s, the increasing burden of chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) has led to a shift in nutrition policy to address them. People are beginning to realize that the key to diet and disease is not simply explained by nutrition-focused indicators; In other words, the synergistic effects of different foods and the overall effects of nutrition (i.e., in the form of dietary patterns) are most valuable in addressing the burden of NCDs.

Figure 1. Historical evolution of dietary patterns. From the discovery, isolation and synthesis of individual nutrients to the exploration of the complex biological effects of foods, the science of nutrition has changed and advanced complex thinking. Future research priorities for the field are shown. Understanding the evolution of dietary patterns can provide important insights into the current state of diet-related diseases. Abbreviation: CMD, cardiometabolic diseases; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension.

Dietary patterns are defined as the amounts, proportions, variety or combination of different foods, beverages and nutrients (when available) in diets, and the frequency with which they are typically consumed. In the last two decades, many different sources and scientifically supported empirical or commercial dietary patterns have become widespread and inspired a large amount of NDE-related research, such as the Mediterranean diet, vegetarian diet, dietary approaches to stop hypertension ( DASH), the ketogenic diet (KD), etc.

Current evidence suggests that healthy dietary patterns are the most promising interventions to improve symptoms and reduce the risk of NDE.

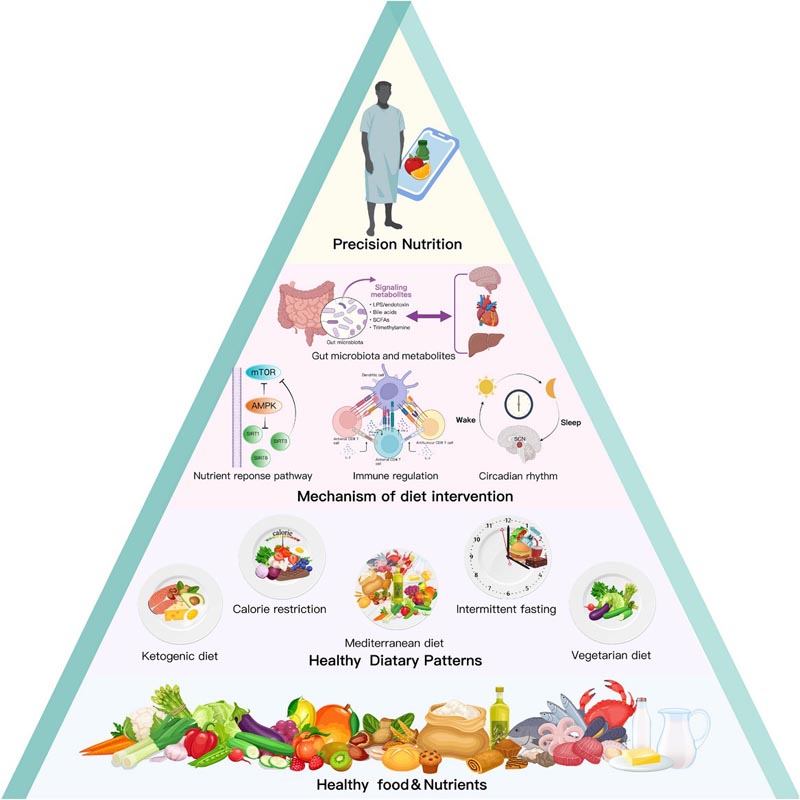

Further enriching clinical studies and gaining a deeper understanding of the relationship between dietary patterns, gut microbiota, and ECM will help refine nutritional science at the molecular, biological, and metabolite levels. This review article focuses on the latest clinical and mechanistic evidence for improving ECM through dietary patterns, presenting new perspectives and research directions to understand how cardiometabolic pathways are driven and organized, ( Figure 2 ).

Figure 2. From healthy foods, nutrients and dietary patterns to cardiometabolic health. The research process for analyzing nutrition and cardiometabolic health is shown from bottom to top. Phase 1: Identification of essential nutrients and healthy foods, such as vegetables and fruits, whole grains and plant-based oils (level 4). Phase 2: Establishment and development of different types of dietary patterns, such as vegetarian diets, Mediterranean diets, ketogenic diets, calorie restriction and intermittent fasting (level 3). Phase 3: Exploring the molecular mechanisms of dietary interventions, including nutrient response pathways, immune regulation, the role of gut microbiota and metabolites, and circadian rhythms (level 2). Phase 4: Provide personalized dietary strategies to patients with cardiometabolic diseases (CMD) based on genetic dietary interactions (level 1). Abbreviation: AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; SCFA, short chain fatty acids; SIRT, Sirtuin

| 2. Dietary patterns with potential for cardiometabolic health |

The definition of a healthy diet is constantly evolving, reflecting our growing understanding of the roles of different foods, nutrients, and dietary combinations in health. For almost 20 years, numerous and growing clinical and basic studies have developed a series of dietary patterns that can be defined as “heart-healthy diets.”

These dietary patterns differ in composition and approach, but all have varying degrees of ability to maintain multiple risk factors, including weight, blood glucose, blood pressure (BP), and blood lipids, within an ideal range. For example, body mass index (BMI) <25 kg/m2 and waist circumference (WC) ≤88 cm (women) ≤102 cm (men), fasting plasma glucose (FPG) <100 mg/dl, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) <5.7%, total cholesterol: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (TC:HDLc) <3.5:1, BP <120/80 mmHg without taking medication and without signs of CVD.

We will focus on three types of dietary patterns based on previous studies and diet composition and approach, (1) dietary restrictions, (2) traditional regional diets, and (3) diets based on the control of macronutrient or food content.

> 2.1. Dietary restriction

Dietary restriction is the most common therapeutic dietary pattern to achieve disease goals by limiting unfavorable metabolic factors. Two main types of implementation strategies are commonly used: one is the restriction of general dietary calories, such as caloric restriction (CR) and fasting, and the other is the restriction of macronutrients in foods, including protein restriction in the diet. diet (PR), dietary carbohydrates and fats.

- 2.1.1. Calorie restriction

CR is generally defined as a dietary pattern that reduces average daily caloric intake by 25% to 30% without affecting the intake of other essential nutrients. It has been shown that CR can prolong the body’s lifespan by reducing basal metabolic rate (BMR), suppressing inflammation and oxidative stress, and improving insulin sensitivity.

The CALERIE-2 trial demonstrated that a 2-year CR intervention (average energy intake reduced by 11.9%) not only improved abnormal cardiometabolic risk factors but also maintained positive effects on cardiometabolic profile during the stabilization period after weight loss.

In addition to the traditional approach of reducing calorie intake outside of each meal, CR can be combined with other lifestyle or dietary patterns to achieve greater metabolic benefits, such as physical exercise.

Other studies have shown that CR combined with intermittent fasting (IF), called intermittent caloric restriction (ICR), can produce the same or even better cardiometabolic benefits than continuous caloric restriction (CCR). This may be related to the fact that it is easier for people to commit to ICR than to CCR.

- 2.1.2. Fast

Fasting is the intentional cessation of solid foods and stimulants (caffeine, nicotine) for a limited period of time. Compared to CR, which must strictly control types of food intake and monitor energy intake, fasting can be achieved by simply ensuring that no food is consumed for a period (>12 h). This simplicity and ease of compliance has contributed to the rapid popularity of fasting as an alternative dietary strategy to CR. The main fasting therapies currently available include IF, long-term or prolonged fasting (LF), and fasting-mimicking diets (FMD).

Intermittent fasting: starvation of less than 2 days and compliance alternating fasting and eating ad libitum. The most studied IFs are alternate-day fasting (ADF) and time-restricted fasting/eating (TRF/TRE).

ADF is a fasting pattern in which fasting days and feeding days alternate at 24-h intervals. This alternative fasting behavior causes widespread positive systemic effects. TRF/TRE is a dietary pattern that restricts daily food intake to a specific period; In this way, it improves metabolic rates and protects the body from diseases such as obesity, regardless of CR.

Long-term or prolonged fasting: fasting from 2 to 21 days or more. In general, medically supervised LF is an effective and safe form of fasting to treat NDE. However, it is strongly recommended that LF or similar fasting interventions be performed only under the supervision of a medical professional.

Fasting-mimicking diets : A low-calorie, low-protein diet for 5 consecutive days per month, recommended 1 to 6 months per year. This periodic dietary strategy offers benefits comparable to those of CR while effectively avoiding the risk of malnutrition, thus having great potential to promote cardiometabolic health.

- 2.1.3. Dietary protein restriction

The ratio of dietary nutrients also influences metabolic health. Reducing dietary protein intake optimizes and prolongs lifespan, regardless of calorie intake. Maintaining a low protein intake can ensure efficient weight loss results and glycemic control in patients with obesity.

- 2.1.4. Carbohydrate restriction in the diet

Excess carbohydrates lead to endocrine dysregulation marked by hyperinsulinemia, promote calorie deposition in fat cells, and thus induce ECMs, such as obesity and T2DM, by increasing hunger and decreasing metabolic rate. Therefore, restricting carbohydrate intake (LCD) is important to improve health.

- 2.1.5. Fat restriction in the diet

Current evidence suggests that low-fat diet (LFD) primarily plays a positive role in weight loss and improving body composition. However, in other reports, compared to other diets such as the LCD and the Mediterranean diet, the metabolic benefits of LFD are not significant and the long-term effects of weight loss were inconsistent. Therefore, it is generally not the first choice for NDE patients.

> 2.2. Traditional regional diet

Results from several epidemiological surveys, prospective cohort studies, and large works have shown that populations in many regions, such as the Mediterranean coast, northern Europe, Japan, and southern China, generally have a lower prevalence of NDE and a higher life expectancy, which may be related to their healthy dietary patterns based on local culture, customs and food resources.

- 2.2.1. Mediterranean diet

It has evolved into a modern diet characterized by a high consumption of virgin olive oil, whole grains, nuts, fruits, vegetables and legumes, a moderate intake of fish, shellfish, dairy products and red wine, and a reduced consumption of red meat, processed meat and sugar. The landmark PREDIMED study demonstrated an approximately 30% reduction in the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular death, and new-onset T2DM in patients at high cardiovascular risk who received a Mediterranean diet intervention for 4.8 years.

- 2.2.2. Nordic Diet

It is a dietary pattern that combines the Nordic nutrition recommendations, issued by five Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden) with Nordic foods. It emphasizes traditional, environmentally sustainable and locally sourced healthy foods that encourage high consumption of leafy and root vegetables, berries, whole grains, fatty fish, legumes and canola oil. Growing clinical evidence suggests that the health benefits of the Nordic diet are at least equivalent to those of the Mediterranean diet.

- 2.2.3.Traditional Asian diets

It features large portions of seasonal fruits and vegetables, freshwater fish and shrimp, soy products, moderate amounts of unrefined carbohydrates such as rapeseed oil and brown rice, and a light, oily cooking method. Studies have shown that the benefits in reducing weight, BP, and blood glucose levels are comparable to those of the Mediterranean diet and that the benefits in preventing hypoglycemia and maintaining nocturnal glucose homeostasis are superior to those of the Mediterranean diet. Mediterranean diet.

> 2.3. Diet based on the control of macronutrient or food content

In addition to dietary restrictions and regional diets, there is another type of dietary pattern that derives from the additional emphasis on the nutrients and foods that constitute it. For example, plant-based diets (PBDs) with an emphasis on plant products, DASH diets with low levels of salt and sodium, KD with ketone production, and Mediterranean-DASH intervention diets for delay neurodegenerative disease (MIND) with a focus on foods that improve cognitive components.

- 2.3.1. Plant-based diet

PBDs are a diverse group consisting of vegan, lacto-ovovegetarian, and semi-vegetarian diets. It is characterized by the maximum intake of plant products and the reduction or elimination of the consumption of foods of animal origin. Data from large prospective cohort studies have consistently shown that vegetarians exhibit lower all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease-related mortality, and less cardiometabolic risk than meat eaters.

- 2.3.2. ketogenic diet

A KD is a high-fat, very low-carbohydrate formula diet, with moderate levels of protein and other nutrient intake. The central goal is to change the way the body provides energy through strict carbohydrate restrictions, triggering a state of nutritional ketosis. It can significantly improve weight loss, body fat mass, BMI, BP, blood glucose level and HbA1 level. However, KD has some potential risks, such as elevated LDL-c and, in some cases, ketoacidosis and kidney disease.

- 2.3.3. DASH and MIND diets

The DASH and MIND diets are dietary patterns established for the treatment of specific diseases (high blood pressure, cognitive impairment) and are closely related to the Mediterranean diet, with a similar dietary structure.

The DASH diet was derived from the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension study , which evaluated the effects of dietary patterns on BP. Its richness in fruits and vegetables, low-fat milk and whole grains, moderate amounts of nuts and legumes, and reduced amounts of red meat, fats, refined sugars, and sugar-sweetened beverages exhibited considerable blood pressure-lowering effects.

Another dietary pattern, the MIND diet, combines the beneficial elements of the DASH and Mediterranean diets with a special emphasis on neuroprotective and cognitive-enhancing dietary components, such as leafy green vegetables and berries. Considering that the MIND diet is composed of two diets associated with a reduced risk of CVD, it is also considered to have some potential to improve cardiometabolism.

| 3. Potential mediating mechanism of the effects of dietary patterns |

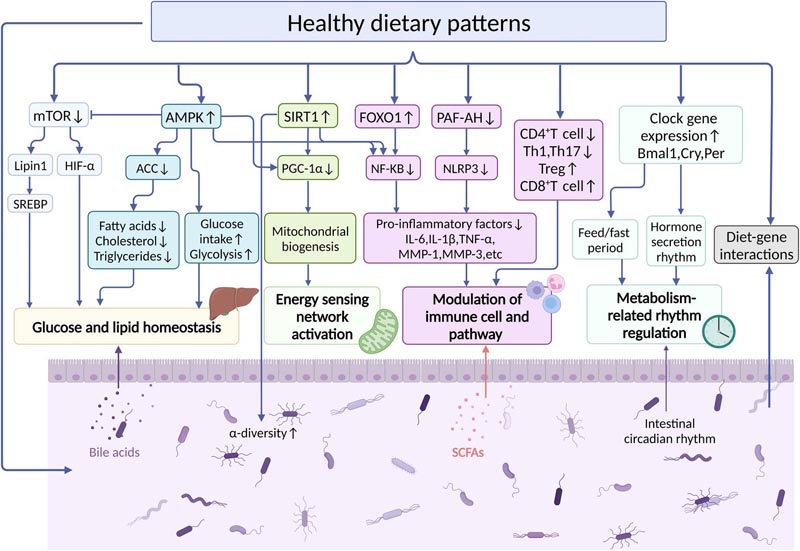

The metabolic benefits of dietary patterns in ECM are achieved by regulating several key interrelated pathways, including regulating nutrient-sensing pathways to maintain energy and glycolipid balance, modulating immune system homeostasis to suppress inflammatory responses and improvement of gut microbiome composition and restoration of altered circadian rhythm, promoting a healthy metabolic phenotype ( Figure 3 ).

Figure 3 . Key molecular mechanisms by which dietary patterns affect cardiac metabolism. Dietary patterns that regulate nutrient-sensing pathways (including mammalian target of rapamycin [mTOR], AMP-activated protein kinase [AMPK], and sirtuin-1 [SIRT1]), the immune system, the gut microbiome, and circadian rhythms and their associated signaling events. Elucidating the mechanisms of dietary intervention in cellular stress response and host metabolic dysfunction at the molecular, cellular, and metabolite levels will help create more precise and dynamic dietary strategies. Abbreviation: ACC, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; FOXO1, forkhead box protein O1; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α; IL, interleukin; MMP, matrix metalloprotease; NF-kB, nuclear factor-kappa B; NLRP3, NACHT, LRR, and PYD domain-containing protein 3; PAF-AH, platelet-activating factor acetylE:hydrolase; SCFA, short chain fatty acids; Th, T-helper; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; Treg, regulatory T cells.

> 3.1. Nutrient response pathways

- 3.1.1. Mammalian target of rapamycin

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) belongs to the phosphatidylinositol kinase-related kinase family. Numerous studies have shown that genetic modification, rapamycin and dietary restrictions can inhibit mTOR overactivation, which could improve lipid and glucose homeostasis, reduce metabolic damage and aging.

- 3.1.2.AMP-activated protein kinase

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), an important kinase in the regulation of energy homeostasis, is one of the key regulators of energy sensing and metabolic homeostasis in eukaryotic cells and is involved in several signaling pathways, including mTOR signaling.

Dietary restrictions, such as CR or fasting, can regulate energy metabolism by activating the AMPK pathway, which drives lipid droplet fusion and lipolysis, effectively reducing the risks of obesity and related metabolic disorders.

- 3.1.3.Sirtuin-1

Sirtuins are a class of NAD+-dependent deacetylases conserved from bacteria to humans. Among them, Sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) is one of the most sought-after members and a key regulator in metabolism, immune response, and aging.

> 3.2.Immune Regulation

Immune dysregulation has long been recognized as an independent risk factor for the development of NDE. As a primary source of metabolic fuel, diet plays an important role in the immune defense response. The body’s nutritional status, dietary intake patterns, and nutritional supplements (e.g., vitamins and minerals) can positively or negatively affect immune system functions such as innate immunity, adaptive immunity, and the microbiome.

> 3.3.Intestinal microbiota and its metabolites

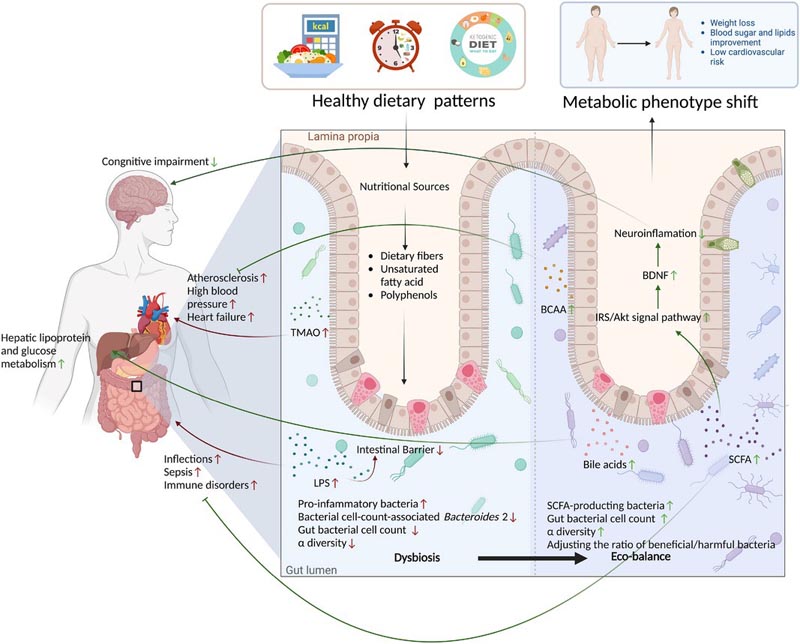

The gut microbiota and its metabolites are not only key signaling centers in the regulation of cardiometabolism, but also important risk factors for individual-level differences in NDE prognosis. Dietary restriction or modification may counteract the metabolic damage associated with obesity by altering the composition and function of the gut microbiota.

The gut microbiota may also influence host metabolic phenotypes by inversely affecting appetite and dietary preferences. Therefore, the benefits of dietary patterns on cardiometabolism may be much greater than we thought, even beyond genetic and environmental factors, as shown in Figure 4 .

Figure 4. Schematic diagram of diet-intestinal microbiota-host metabolism. This figure represents the direct effects of healthy dietary patterns on the gut microbiota to influence host metabolic phenotypes. This includes increasing the diversity of the gut microbiota, adjusting the ratio of beneficial and harmful bacteria, and promoting increased secretion of the beneficial microbial metabolites short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs). Abbreviation: BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; TMAO, trimethylamine oxide.

> 3.4.Circadian rhythms

Disturbed circadian rhythms are a hallmark of NDEs, such as obesity, T2DM, and atherosclerosis, and are closely related to poor eating habits.

Furthermore, the gut microbiome has a complex bidirectional regulatory role with the circadian system. The rhythmic oscillations of microorganisms are the basis of their time-specific functions, including promoting digestion and energy metabolism during the day or active period, and detoxification during the night or rest period.

4. Conclusion The impact of food on health has been an important topic throughout human history. In this review, cutting-edge developments among restrictive diets, regional diets, and various patterns based on macronutrients and controlled food groups and ECM are summarized, demonstrating the multi-dimensional appeal for improving cardiometabolic health. However, the lack of large case-control studies and long-term longitudinal cohorts may prevent us from determining how these dietary patterns may prevent NDE or delay its development. More in-depth work is still needed, such as large, cross-region prospective studies, more accurate and rapid questionnaires and dietary assessment tools, and unraveling the specific mechanisms by which dietary patterns affect ECM at the genetic, molecular, and genetic levels. microbiota and metabolites. Providing more precise and dynamic personalized nutritional advice based on gene-diet interactions than is currently available should be a priority and an important direction for future nutritional health policy development. The gut microbiota is a novel player in the pathophysiology of NDE and a predictor of individual response to dietary interventions. In the future, we can optimize nutrient ratios based on patients’ microbiota profile. The scientific findings of the present study and the literature support the use of dietary strategies to prevent, delay, and even reverse NDE. Furthermore, based on the understanding of the complex interactions between diet, gut microbiota and the ECM, as well as the development of new model systems and emerging tools in modern biology, personalized and low-cost dietary interventions that offer care Accurate nutritional information and treatment solutions can be made available to the public. |