Many adults spend more than half of their waking hours sitting, and this pattern was further amplified by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) pandemic. In this review, we advocate an approach to the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease that involves “sitting less and moving more . ” Observational and experimental evidence on the potential cardiovascular health benefits of regularly reducing and interrupting sitting time underlies this approach along with an emerging understanding of biological mechanisms that point to a rational basis for doing so.

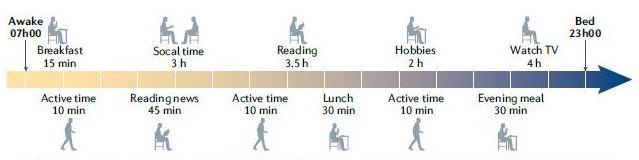

Physical inactivity , defined as a level of activity that is insufficient to meet current physical activity guidelines, has long been known to be a major contributor to cardiovascular disease risk. Adults may meet or exceed public health guidelines for physical activity, but they may also spend most of their waking hours sitting ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 | Daily activities that involve sitting. For non-working adults who sleep 8 hours in a 24-hour cycle, the remaining waking hours (16 hours) can be filled with various recreational activities and activities of daily living. In this hypothetical example, these adults may be considered physically active according to current physical activity guidelines because they accumulate up to 30 minutes of physical activity throughout the day. However, these people may also spend several hours (14.5 hours) sitting during meals, socializing, and enjoying recreational activities. Therefore, despite meeting current physical activity guidelines, non-working adults may spend up to 90% of their remaining waking hours sitting. This substantial sitting time is not an atypical pattern for many older adults and could be characterized as “active but also highly sedentary.” This example highlights the importance of not only focusing on time spent in activity, but also on reducing the time spent sitting during waking hours (or ’sit less and move more’).

There is a strong inverse relationship between sedentary behavior and total physical activity, with the strongest association observed for light intensity physical activity.

This inverse relationship highlights a fundamental principle that any time spent in sedentary behavior displaces time spent in total physical activity. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have amplified the importance of addressing the balance between sedentary behavior and physical activity.

Daily sitting and movement patterns can be assessed by an activity monitoring device illustrating how these device-based measurement capabilities can provide new insights through more powerful and higher resolution lenses. These instruments have considerably sharpened the scientific approach that can help characterize daily activity with greater degrees of precision, particularly with new insights into the underrecognized role of sedentary behavior (not only total time spent sitting, but also patterns of sitting time). , including brief physically active breaks).

| Observational evidence |

The first recommendation of the 2018 US Physical Activity Guidelines for adults (18 to 64 years) and older adults (≥ 65 years) emphasizes promoting sitting less and moving more for everyone and getting some physical activity is better than nothing, while those who sit less and do any amount of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity gain some health benefits.

Population-based studies using self-report measures suggest that daily sitting time in adults typically ranges between 5 and 8 hours. Examination of trends over the past 10 years shows that self-reported sedentary time has increased by about 1 hour per day.

However, device-based estimates from population studies and large cohorts show that the average daily sedentary time in adults could be much higher than indicated in previous estimates that were based on self-reports and, in fact, could be in range from 7.7 to 11.5 hours per day.

Despite the effects of sedentary behavior on total physical activity levels, studies in younger (mean age 22 years) and older (mean age 64 years) adults have shown that sedentary time measured by the device is inversely associated with measures cardiorespiratory fitness and functional fitness. Even after adjusting for time spent in moderate-to-vigorous intensity activity, suggesting that health risks associated with sedentary behavior could be attenuated by increasing fitness levels.

Regarding the findings of the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee that are relevant to cardiovascular disease, the main conclusion is that there is strong evidence available to support that exposure to a large amount of sitting significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular death from all causes and incidence of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Furthermore, findings from a systematic review and harmonized meta-analysis of accelerometer-assessed sedentary time showed that greater sedentary time is associated with an increased risk of death from all causes. In contrast, higher levels of total physical activity, regardless of intensity level, are associated with a lower risk of death from all causes.

| Risk mechanisms related to sitting |

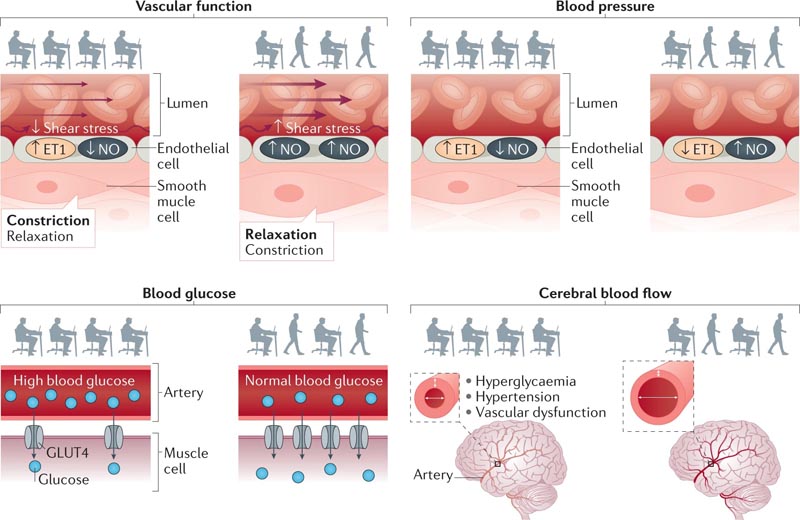

Sitting likely acts through multiple biological systems to regulate vascular function (top left), blood pressure (top right), blood glucose (bottom left), and cerebral blood flow (bottom right). right). Initial evidence suggests that regular physically active interruptions to sedentary time could attenuate these physiological perturbations to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. These pathways could interact to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. ET1, endothelin 1; GLUT4, glucose transporter type 4; NO, nitric oxide.

Laboratory studies have experimentally identified the effect of prolonged periods of sitting, with or without brief physically active interruptions, on cardiovascular risk factors. The scientific justification for these experimental approaches is based on the crucial principle that, by definition, physical activity (i.e., any body movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure) must be the countermeasure to sitting during hours of work. vigil.

> Vascular function

Vascular function is impaired during prolonged periods of sitting, particularly in the lower extremities. In contrast, interruption of prolonged periods of sitting with physically active interruptions significantly improved vascular physiology. Reductions in blood flow and shear stress have been attributed to acute sitting-induced dysfunction.

The mechanisms underlying reduced blood flow and shear stress during sitting are likely multifaceted. The decreased muscle activity during sitting, particularly in the large weight-bearing muscles of the lower extremities, and the subsequent reduction in energy demand lead to a decrease in peripheral blood flow, resulting in a reduction in blood pressure. shearing.

Additionally, decreases in blood flow and shear stress could be related to prolonged gravitational forces that increase hydrostatic pressure within the lower extremities, a mechanism supported by observations of increased calf circumference after prolonged sitting. , indicating venous accumulation.

> Blood pressure

The magnitude of the effect of prolonged sitting on blood pressure-raising or the blood pressure-lowering effect of regular interruptions in physical activity appears to be greater in people with existing cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. These variations in blood pressure may be caused by changes in total peripheral resistance due to the vasoconstrictive influence of norepinephrine.

In the context of blood pressure, the biomechanics of sitting itself could increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Sitting causes flexion and angulation of the arteries of the lower extremities due to hip and knee flexion, which in addition to contributing to decreased blood flow, can also induce turbulent flow and shear stress patterns.

> Blood glucose levels

Postprandial blood glucose, insulin, and triacylglycerol levels are acutely elevated after prolonged periods of sitting. This sitting-induced metabolic dysfunction is attenuated by regular interruptions in physical activity. A meta-analysis of 37 studies showed that regular interruptions of physical activity during prolonged sitting had a significant beneficial effect in acutely reducing glucose and insulin levels compared to continuous sitting.

The main mechanism that could explain the influence of sitting on glucose metabolism is related to the uptake of this substrate by skeletal muscle through insulin- and contraction-mediated pathways. Both pathways result in the translocation of glucose transporter 4 to the plasma membrane, facilitating glucose uptake and therefore reducing blood levels.

> Cerebral blood flow

Sitting-induced deficiencies in glycemic regulation could also affect cerebrovascular function.

This parameter encompasses the mechanisms that maintain constant cerebral perfusion, preventing ischemic brain injury and damage. It has been suggested that acute hyperglycemia reduces regional cerebral blood flow and increases insulin secretion, promoting glucose clearance.

In older adults (mean age 78 years), 3 hours of sitting increased blood pressure and cerebrovascular resistance. Increased vascular resistance causes arterial remodeling, reducing lumen size, which over time could reduce cerebral blood flow.

> Inflammation

Increased systemic inflammation caused by prolonged sitting could contribute broadly across different systems to factors that may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. The possibility that chronic low-grade inflammation and oxidative stress, which result in arterial stiffness, may contribute to chronic elevations in blood pressure due to prolonged sitting remains questionable.

> "Exercise resistance" induced by sitting

Prolonged, uninterrupted sitting could further increase the risk of cardiovascular disease by promoting the development of sitting-induced “exercise resistance,” implying reductions in typical responses observed after acute exercise. Acute exercise reduces plasma glucose, insulin, and triglyceride levels. However, 4 days of prolonged sitting prevents these expected beneficial postprandial responses to acute exercise.

> Future directions

Experimental evidence relevant to understanding the mechanisms by which sedentary behavior affects major pathways implicated in cardiovascular disease is currently largely restricted to the acute effects of prolonged sitting.

| Sedentary behavior reduction trials |

Increased interest in sedentary behavior as a public health problem has stimulated the conduct of more than 30 controlled trials of interventions to reduce sedentary behavior in adult populations since 2003. These strategies can be classified into three types: environmental interventions designed to changes in a particular behavioral environment (e.g., sit-stand workstations in workplaces), educational and motivational interventions that focus on the individual’s behavior (e.g., smartphone apps and educational programs), and multicomponent interventions that incorporate both environmental and educational or motivational elements.

Environmental interventions produced the greatest reduction (-40.6 minutes per day), followed by multicomponent (-35.5 minutes per day) and behavioral (-23.8 minutes per day) interventions. The observed reductions in sedentary behavior, particularly for environmental and multicomponent interventions, are clinically relevant because sedentary time has a high inverse correlation with low-intensity physical activity.

However, to date most of the evidence comes from workplace-based interventions to reduce sedentary behavior. In comparison, a meta-analysis revealed that workplace physical activity interventions have produced moderate combined effects on body mass and waist circumference, while reductions in blood pressure and blood lipid and glucose levels no relevant ones were observed.

Exciting possibilities arise for future research and clinical innovations. Technological advances in consumer devices provide particular opportunities. Data from wrist-worn activity trackers now

They provide information on interruptions in sedentary time and on light-intensity activity and moderate-to-vigorous-intensity activity. These data can already provide clinical starting points to address reductions in sitting time and increases in total physical activity, along with relevant goal setting and objective feedback for the individual.

| Sit less and move more |

Interactions between sedentary behavior and physical activity on cardiovascular disease risk have been the subject of intense scrutiny in a number of prospective epidemiological studies; Crucial conclusions related to this interaction are summarized below.

Physical inactivity and sedentary behavior are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease incidence and death. Replacing sedentary behavior with any intensity of physical activity (i.e., movement) will have health benefits, and greater benefits will be seen when sedentary behavior is replaced with moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity.

Higher levels of self-reported session time were associated with higher all-cause mortality in moderate-intensity physical activity categories. However, this correlation did not exist in the highest category of physical activity, in which the risks of sitting are mitigated.

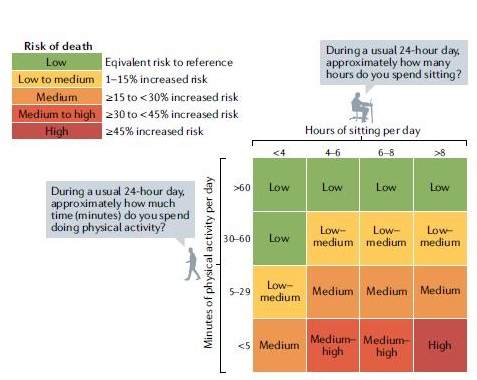

Although the joint associations between prolonged sitting, physical inactivity, and other health outcomes (e.g., cardiovascular events and type 2 diabetes mellitus) are beginning to be clarified, we can nevertheless consider how mortality evidence from all causes to create a “matrix” of mortality. This matrix will uniquely combine sitting time and physical activity in a way that has relevance to the application of novel management approaches in clinical practice.

An SIT-ACT all-cause death risk matrix can help clinicians develop treatment decisions for patients living with or at risk of developing cardiovascular disease ( Figure 2 ). Answers to two separate questions determining daily sitting time and physical activity time are critical to the application of this risk prediction model.

Figure 2 | The SIT-ACT risk matrix. Representation of the SIT-ACT risk matrix showing the interactive influences of sedentary behavior and physical activity (physical activity includes walking and moderate-to-vigorous intensity activities) on all-cause mortality. The highest risk of death is evident in people who spend the most time sitting and do the least amount of physical activity. Opportunities for risk reduction include increases in physical activity (to >5 minutes per day), reductions in sitting time (to <8 hours per day), or the combination of increases in physical activity and reductions in time spent sitting (e.g., transition to low to medium risk by increasing physical activity to >5 minutes per day and decreasing sitting time to <4 hours per day).

| Implications for clinical practice |

Although regular, structured physical activity (exercise) effectively reduces cardiovascular risk and improves relevant outcomes, exercise adherence, even within structured cardiac rehabilitation programs, may be suboptimal. Additionally, sitting-induced “exercise resistance” (as described above) could attenuate the benefits of exercise among those performing suboptimal levels throughout the day.

Because physically inactive people have a higher overall risk of acute cardiac events than their physically active counterparts, the American College of Sports Medicine recommends light to moderate intensity exercise in the first instance, especially for people who are habitually inactive. Specifically, among inactive adults, reducing sedentary time and therefore increasing low-intensity activity could provide sufficient stimulus and progressive overload leading to valuable improvements in cardiorespiratory and musculoskeletal function.

A “ladder” approach can be applied that initially focuses on reducing and interrupting sitting time. This approach initially increases standing and walking time, progressing to increasing volumes of light-intensity physical activity and then increasing moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity. The ladder approach contrasts with the healthy but formidable primary goal of transitioning from a chronic inactive state to regular participation in moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity and improved cardiorespiratory fitness.

A first step toward integrating more movement into patients’ daily lives could include goals of reducing total sitting time by 30 minutes per day or stopping prolonged periods of sitting throughout the day. An older adult with cardiovascular disease could, for example, increase leg strength simply by adding several sit-to-stand transitions throughout the day. This extra movement may increase your ability to do more physical activity, such as climbing stairs.

| Conclusions |

Prolonged, uninterrupted periods of sitting contribute to the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Time spent sitting also reduces total physical activity time, resulting in decreased overall skeletal muscle activity and leading to detrimental effects on cardiorespiratory fitness and multiple metabolic processes related to cardiovascular health.

Taken together, both epidemiological and experimental evidence suggest that spending less time sitting will lead to a cardiovascular health benefit. In clinical practice, a combined approach that emphasizes sitting less and moving more could amplify the transition to more physically active lifestyles with cardiovascular health benefits.

In this review, we have considered the current strengths and limitations of the available evidence, highlighting some of the emerging opportunities for future research and suggesting initial implications for clinical practice.